Grand National 2014: Humans beating horses in race to get faster

- Published

2011 Derby-winning horse Frankel, and 100m world record holder Usain Bolt

An estimated global audience of 500 million will tune in to see who wins Saturday's Grand National, the world's most famous steeplechase.

Anyone placing an each-way bet will keep an eye on the top five. Racing enthusiasts will note the winning jockey, trainer, owner and starting price. Most of us will not know, or care, about the winning time.

Yet this masks a big question for horse racing. While almost every record in athletics has been broken repeatedly over the past 50 years, horses' race times are stagnating. Why?

Research conducted by Mark Denny, a leading biologist at Stanford University in California, suggests horses have not run the Triple Crown races, external in the United States much quicker since the late 1940s, a trend largely reflected in the major races in the UK.

Are horses more evolved than humans? Is it the human desire to set new standards? Is it because the human diet has improved considerably compared to horses?

BBC Sport spoke to a variety of experts and came up with eight possible reasons.

Horses are already close to perfection

Humans have been selectively breeding horses for several thousand years, and thoroughbreds for racing for about three centuries.

"Compared with humans, racehorses are incredibly advanced athletes. Any significant gains in physiology have already been achieved," says Andrew Byers, a senior lecturer in equine sports science at Nottingham Trent University.

Horses are conditioned to the limit of their physical abilities for racing

In 1988, Professor Patrick Cunningham,, external a former chief scientific adviser to the Irish government and expert in animal genetics, noted that selective breeding had not yielded faster times in the previous 50 years.

He suggested the physiological limit of racehorses might have been reached, for example, in dealing with lactic acid build-up in muscles during performance.

The stud market remains big business worldwide and it is almost impossible to win races without horses from quality stock.

However, Mark Denny believes that to become faster still, horses would also become more fragile. "Stronger muscles and better lung capacity doesn't get you much if tendons and bones can't withstand the extra stress," he notes.

Dr Peter Webbon, a veterinary adviser to the General Stud Book,, external which documents the breeding records for thoroughbreds in Britain and Ireland, says: "Horses have evolved to become fantastic athletes because in the wild their main defence is to run away.

"Compare that with humans, who are not natural athletes and wouldn't even be able to catch a hare. But humans are very adaptable and some can be trained to become good athletes."

Horses are old pros, humans relatively new

Unlike humans, racehorses have been 'professional athletes' for much longer. When Sir Roger Bannister broke the four-minute mile barrier in May 1954, he was working as a junior doctor. "It's hard to imagine Royal Tan, who won the 1954 Grand National a few weeks earlier, being asked to pull along a milk float in the morning ahead of the big race," says Byers.

In the era before television coverage of the Olympics, any athletes paid for their performances were treated as outcasts. American athlete Jim Thorpe was stripped of his gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon in the 1912 Games because he had once accepted small amounts of money for playing semi-pro baseball during his college summers.

Thorpe's medals were only posthumously restored 30 years after his death. Since the latter half of the 20th century, an increase in the funding of training has allowed athletes to devote their time to getting better, so it is no surprise that records have been tumbling.

Winning times - Grand National and Epsom Derby plus world athletics records - last 100 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Year | Grand National (4.5 miles) | Epsom Derby (1.5 miles) | 5,000m Men's WR | Marathon Men's WR |

1914 | 9mins 58.8secs (going good) | 2mins 38.4secs (*going unknown) | 14mins 36.6secs | 2hrs 36mins 6secs |

1934 | 9:20.4 (good to firm) | 2:34.0 * | 14:17.00 | 2:29.02 |

1956 | 9:21.4 (good) | 2:36.4 * | 13:36.80 | 2:17.39 |

1984 | 9:21.4 (good) | 2:39.1 (good) | 13:00.41 | 2:08.05 |

1990 | 8:47.8 (firm) - record time | 2:37.3 (good to soft) | 12:58.39 | 2:06.50 |

2013 | 9:12.0 (90 yards less - good to soft) | (*2010 - record of 2:31.33 - good to firm); 2:39.06 (good to soft) | 12:37.35 | 2:03.23 |

Is bigger better and faster?

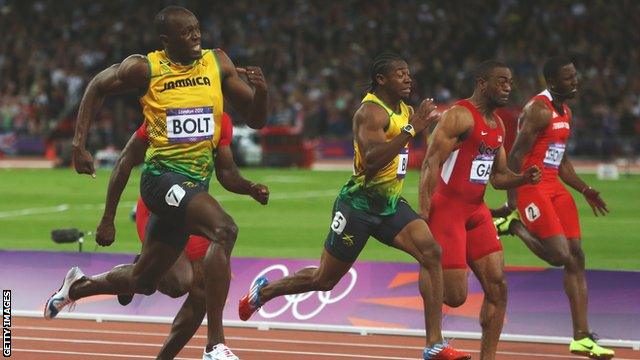

Records show humans have been steadily increasing in height for the last 150 years. Six-time Olympic champion Usain Bolt's stature (6ft 5in, or 1.95m) adds to his athletic prowess with a giant stride length, even if he has to expend greater power and energy to overcome drag caused by air resistance.

Bolt took 41 steps on his way to 100m gold in London, whereas Yohan Blake [5ft 11in, or 1.80m] who won silver, needed 46. On the other hand, sprinting is not all about size. Bolt's fellow Jamaican Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, who won the women's 100m at the last two Olympics, is one of the smallest athletes in her field at about 5ft (1.52m).

Bolt's size and giant stride length give him a natural advantage over his sprint rivals

Thoroughbreds have always varied greatly in size. A recent study by Simon Rowlands, an expert from horse racing analysts Timeform,, external suggests bigger horses do, on average, perform better. However, that needs to be viewed in the context of sprinters tending to be bulkier than stayers, as indeed is the case with human athletes. As his data comes from horses' weights only, he says for 'bigger' read more muscle mass, not just height.

Buyers of racehorses are much more interested in their family history than size. And while thoroughbreds are not measured when they are registered in this country, Dr Peter Webbon says "there's no reason to believe that the modern thoroughbred is taller".

Speed versus stamina

Horses still break track records from time to time. The 2010 Derby winner Workforce, external shaved just under a second off the old record for the Epsom Classic.

This is not so surprising when you consider the advances in training. The top horses today help build their endurance in swimming pools, relax their muscles in solariums and train all year round on all-weather gallops.

A horse exercises in a swimming pool at trainer Jonjo O'Neill's yard in Gloucestershire

Yet Ian Balding, trainer of the great 1971 Derby-winning Mill Reef, and father of broadcaster Clare Balding, says the philosophy of preparing horses has changed over the past 40 years. Breeders and trainers now prioritise speed over stamina.

Ian says his son Andrew Balding, who took over the family training business,, external prepares a horse to be as good as it can be over six furlongs, even when it is going to run a 12-furlong (one-and-a-half mile) race. The thinking is that if the horse is a stayer, it will run the distance well, as long as it is fit.

The great Mill Reef, here winning the 1971 Derby, won 12 of his 14 races and was second in the other two

Diet - less beer, more protein

Stanford University biologist Mark Denny attributes most of the increase in size in humans to better nutrition.

"Large numbers of the human population were protein-deprived until relatively recently, but I doubt that thoroughbreds have been historically malnourished," he says.

In the last 40 years, thoroughbreds have moved away from an eclectic diet which included bran mash, oats, honey and beer - the Irish legend Arkle,, external widely considered to be the greatest steeplechaser of all, was said to be partial to a drop of Guinness - to one consisting almost exclusively of high-energy cereal and protein cubes.

Footwear - lighter spikes v comfy metal

Aerodynamic clothes and improved footwear are helping today's athletes run faster, jump higher and limit the damage done to their feet in races.

"When Jesse Owens was winning the Olympics in the 1930s, shoes were made of leather and weighed several pounds," explains John Brant, an athletics coach who has trained runners from grassroots to elite level for 33 years.

"Today's top athletes wear spikes weighing a few ounces, giving them an advantage compared with their predecessors. They go through a couple of pairs every week."

The money in athletics allows manufacturers to sacrifice durability and make lighter shoes. And while shoes worn by racehorses are also lighter, Cheltenham's clerk of the course Simon Claisse says "they are still a piece of metal on the end of a hoof, something which has barely changed in centuries".

Safer tracks mean slower races

Since the mid-1990s, the British Horseracing Authority (BHA) has introduced safety measures which include making running conditions kinder for horses.

Racecourses are directed to provide good ground for jump races, external (and no firmer than good-to-firm), while Flat courses should aim to provide good-to-firm ground. As a result, many courses are watered before races to soften the turf.

The BHA says: "A slower pace of race does equate to safer races, especially in jump racing. A softer surface results in more give, less limb impact and more slide if a horse falls at an obstacle."

In 1990, when Mr Frisk recorded the fastest ever Grand National time of eight minutes and 47 seconds, the going was officially firm. It has not been firm since. "As the ground won't be allowed to get that hard for a National again, I doubt the record will ever be beaten," says Ian Balding.

Mr Frisk beat the previous record of the great Red Rum by 14 seconds in winning the 1990 Grand National

Whereas the racing authorities often prepare slower tracks for horses, it is the opposite for humans. The London 2012 track was built specifically to aid sprinters. And for the first time, seven men in the 100m final ran under 10 seconds.

Horses have to wait for nature to provide the perfect conditions. Simon Claisse cites 2000 as the example, when several records were broken at the Cheltenham Festival.

Claisse says: "We had a very wet winter that year, but good weather dried up the top layer of the track before race week. And that produced a springy surface ripe for fast times. The extra elasticity in the ground gave the horses a return in energy for their efforts."

The kudos is in winning, not beating the clock

Both human and horse races are often tactical, and not focused on records. But human athletes dream of breaking records and are sometimes offered cash incentives to do so.

There are financial spin-offs, sponsorship deals and glory for record-holders. Pacemakers are arranged for athletes attempting fast times. Horses don't generally have that purpose. "As horses scarcely get any kudos for a breaking a track record, jockeys and trainers do not aim to achieve that," notes Timeform analyst Simon Rowlands.

When you watch humans racing, be they on foot or bikes, in boats or motorcars, there is usually a clock in the corner of your screen. That is not the case for big horse races like the Grand National and Cheltenham Gold Cup.

While serious racing enthusiasts keenly observe sectional timing, or split times between furlongs,, external "it's not in the culture of horse racing to focus on times," says Dr Hieke Brown, a lecturer in equine science and thoroughbred management at Oxford Brookes University. "The betting industry concentrates the mind of the punter on winners and placings."

If you are having a wager on Saturday's big race, you'll know that to be true.

- Published1 April 2014

- Published4 April 2013

- Published20 October 2012

- Published15 October 2012

.jpg)