World Championships 2017: Mo Farah's journey from carefree kid to sporting superstar

- Published

- comments

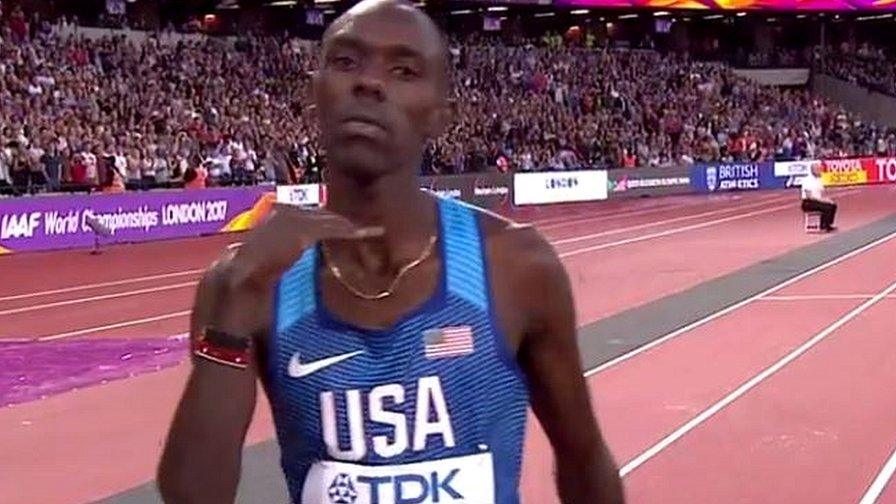

Watch: Edris shocks Farah in 5,000m

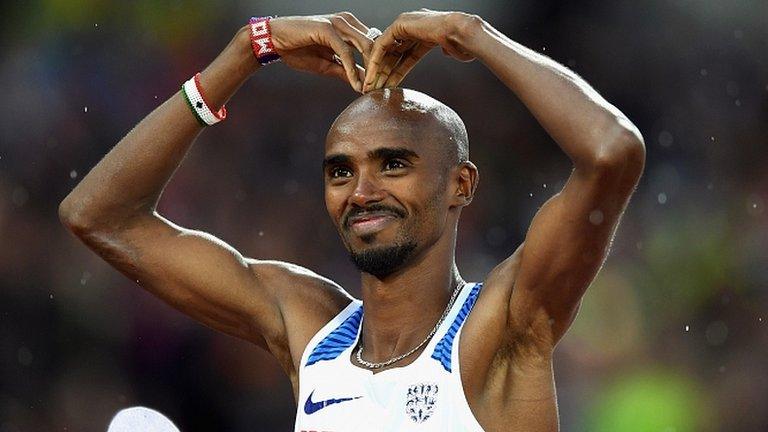

And so that is it for Mo Farah in championship track finals: seven years of wonder, 10 global golds in a row and a silver to finish, dancing under the lights from Korea to Rio, Moscow to Beijing, to London and then back again.

It began with innocence and it ended with a sold-out stadium of his compatriots roaring his name. Along the way he has been both a constant and an agent of change - a guaranteed gold until the very end, a lonely long distance runner every kid and granny in the country knows; a draw big enough to have pubs show his finals on big screens, the face of an open, forward-facing nation in an fractured, introspective time.

British crowds in this stadium and on sofas across the country have made that journey with him. Wonder at the start, an intimacy as it developed with his tactics and celebrations afterwards, a collective desire to see him finish in the perfect way.

Farah's devastation that his last championship race ended with a first defeat since August 2011 was clear as he fell to the Stratford track. The deafening wave of noise that had chased him round the stadium throughout the preceding 12 and a half laps broke into a stunned silence.

The roars soon returned. First the British women's quartet stormed to a 4x100m relay silver that represented a perfect synergy of their burgeoning individual talents. Then GB's men went one better, putting together an impeccable combination of changeovers and legs to win the nation's first sprint relay gold at a World Championships.

Farah reflects on 'amazing journey'

In those moments you sensed a generational shift, a feeling intensified by the sight of Usain Bolt stricken halfway down the home straight, his own valediction ending in pain and defeat and very nearly a wheelchair before he limped away, lost in the bedlam.

Farah and Bolt, old friends, partners in track hegemony over the past decade, had shared a hug on the access road deep under the main stand as the Briton left the arena after his 5,000m and the Jamaican arrived for his sprint relay final.

Just as Bolt had been after his defeat by Justin Gatlin in the 100m final a week ago, Farah is left without the scripted happy ending. The two champions have discovered in the same few days that time catches up with even the fastest of men, although the Briton did win 10,000m gold on the opening day of these championships.

In a strange way Farah's defeat may eventually both bring a greater appreciation for all that has come before and tighten further the bond between him and his audience.

Farah wins world 10,000m title for third time in a row

The problem with perfection is that you can begin to believe there might be nothing else. You can start to think that repetition means it might be easy. You lose the connection between your humble world and theirs.

When flaws eventually show, when muscles that were pushed to their limits finally refuse to give back as they have before, you see the effort and the character that might previously have slipped by unnoticed.

So it was with Farah, who knew coming into the last 70 metres that Ethiopia's Muktar Edris could not be caught but threw everything he had into fighting past Paul Chelimo and Yomif Kejelcha for a silver that at the start of the night he would have considered failure.

As former Olympic and world decathlon champion Daley Thompson said, watching for BBC Sport, it was like watching a gunslinger die with his boots on. So too with Bolt, who has probably known all year that he should have waved farewell after Rio a year ago, but tried forcing his creaking, popping body to respond one final time.

Innocence and wonder always seemed to come naturally to Farah, the naïve immigrant kid who on his first day at Oriel Junior School in Hanworth had gone home with a black eye after trying the least appropriate of his three English phrases ("Excuse me", "Where is the toilet?" and "Come on then") on the playground bully.

Mo Farah winning 5,000m gold at the London 2012 Olympics, the first of four double golds at global championships

In his school races at Feltham Community College he sometimes misunderstood the instructions, took wrong turns and had to double back. As a talented teenager carrying heavy hopes he would be surprised when told how greater success would come - drinking, partying, jumping off Kingston Bridge into the Thames for a dare.

But there was never a naivety in the way he raced as a matured champion, up against 14 other men in global 5,000m finals, posses from other nations ganging up to disrupt his tactics, all trying to mess with his rhythm, sitting in his eyeline or breathing down his neck, slipping an unseen elbow into his ribs or leaning a little shoulder in as pumping arms came together.

Great distance runners must have intuition and intelligence and the physical weapons to utilise them.

They must be aware of what is happening in front of them and behind them and on either side, to calculate what those 14 rivals might want to be doing, and to respond to every challenge thrown at them - a burst from the gun, a punishing jab-hook of laps alternated fast and slow, a wind up from way out, an explosive kick from the bell or final all-out kick down the home straight.

Not all the innocence went with the appreciation of that. After the holy nights of London 2012 and Farah's crescendo to Super Saturday came the hangover: a series of allegations against Farah's coach Alberto Salazar and leaks from the Russian hackers Fancy Bears that made many wonder in a different way.

UK Athletics's review found "no evidence of any impropriety" in Farah nor any reason to "lack confidence" in his training programme. Salazar is still being investigated by the US Anti-Doping Agency.

Farah's family were watching on from the stands once again

Some of those around Farah changed too. An uncomplicated man who lived to run employed PR firm Freuds to help manage his image. His smile, always unaffected and never far away, was repurposed by his shoe sponsor Nike as the subject of an advertising campaign.

And so some wondered and speculated, even as the majority wondered and marvelled.

Saturday night in Stratford, summer evening sky up above all pale blue and purple clouds, stands down below packed with partisans and Union flags, spoke only of belief.

"Would you have been prouder to have done it for Somalia?" a reporter had asked Farah in the aftermath of his 10,000m win in London five long summers ago. The obsessive Arsenal fan had been indignant. "Not at all, mate. This is my country."

As he stepped off the track on Saturday, beaten at last, it still felt that way, both looking at the crowd and the man they had come to roar home. Innocence to some, a wonder to far more.

- Published12 August 2017

- Published13 August 2017

- Published12 August 2017

- Published12 August 2017

- Published13 August 2017