Kell Brook: Machete attack made boxer think he was dying

- Published

Kell Brook on his stabbing ordeal

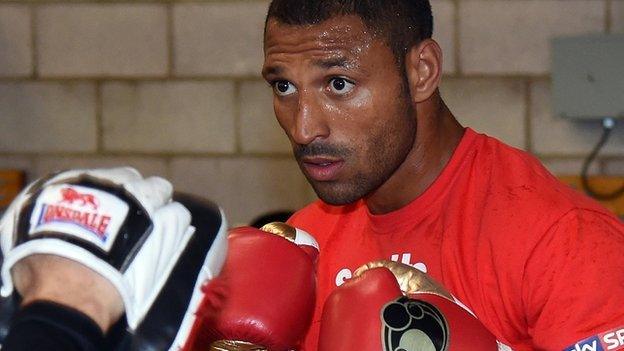

The story of Kell Brook's stabbing is not heartwarming or uplifting. But the best stories often aren't. And at least Brook has a story to tell and is willing to tell it.

"I was lying there helpless and hopeless on the side of the street," says the Sheffield boxer, who was attacked with a machete while on holiday in Tenerife last September, only two weeks after winning the IBF welterweight world title in the United States.

"I was thinking about my kids, my family, looking at the blood pouring out of my leg. Finally I thought: 'I'm dying - this is actually the end'."

We live in an age when trying to nail down an interview with a Premier League footballer is like trying to secure a private audience with the Pope. Not that most Premier League footballers have much to say when they deign to be interviewed. Or, more correctly, when one of their minions allows it.

The modern footballer, like most modern sportspeople, does not have the time to weave a compelling narrative beyond the field of play. Elite footballers, golfers and tennis players hit balls for a living. And when they're not hitting balls, they're in the gym. Or eating healthily. Or recovering from training. Or in bed. Anything but giving interviews.

There are exceptions - Tiger Woods, external springs to mind from recent times. But for the most part, modern sport demands wholesome living. Which is why there has never been a great film made about a real-life footballer or golfer or tennis player. And why film-makers always have, and always will, seek inspiration from boxing. , external

Brook's promoter Eddie Hearn |

|---|

"He's a very good friend but also a client, so from a selfish point of view I was thinking: 'We've got ourselves a welterweight world champion, we've invested a lot of time, effort and money and now he's never going to fight again.' His leg looked like it had been eaten by a shark." |

Boxers are essentially self-employed, freelance workers with plenty of spare time on their hands. Paradoxically, elite boxers, who might only have two or three fights a year, have more spare time than most. A lot of time in which to lose all their money, get fat, engage in torrid affairs, develop drink and drugs problems and crash extremely fast vehicles.

"Boxers don't work nine to five like most of us," says Brook's trainer Dominic Ingle, who has known his charge since he was eight. "They're not normal people - they live in a parallel universe. Everyone should expect the unexpected, that's how life is. But even more so if you're a boxer.

"I've been in boxing all my life and seen so many ups and downs. So when bad stuff happens in boxing, I never think: 'I didn't see that coming.' I think: 'That's the way it is'."

There is no evidence to suggest that Brook, 28, was in any way to blame for the incident that almost killed him. But there is plenty of evidence to suggest that even when boxers don't go looking for trouble, trouble will find them.

The strife and times of British boxers |

|---|

Kell Brook - Stabbed on holiday in Tenerife last September. Suffered career-threatening injuries, two weeks after winning IBF welterweight world title |

Anthony Crolla - Suffered fractured skull and broken ankle apprehending burglars last December. Due to fight for WBA lightweight title a month later |

Jamie Moore - Former European light-middleweight champion was shot in leg and hip while training his fighter Matt Macklin in Marbella last August |

Ricky Hatton - Suffered with alcohol addiction and depression. The former two-weight world champion was admitted to a rehabilitation facility in 2010 |

Herol Graham - Suffered with depression after retiring. Three-time world title challenger attempted to take his own life in 2007. Sectioned in 2008 |

Last December, Manchester lightweight Anthony Crolla suffered a fractured skull and a broken ankle when he tried to apprehend burglars in his neighbour's garden. Crolla was to have challenged for a world title in January, but his dream is now on hold.

"What normal person goes chasing after burglars?" says Eddie Hearn, who promotes both Brook and Crolla. "If I saw someone robbing my neighbour's house, I'd shout 'Oi!' out the window and disappear inside again. But fighters don't think like normal people, they don't think about the consequences."

It was this same attitude that saw a bleeding Brook submit to fate so readily. "I can't even imagine being in that position, seeing blood pouring out of my leg and being seconds from death," says Ingle. "But Kell wasn't even panicking. He just thought: 'This is it - that's just the way it goes.'"

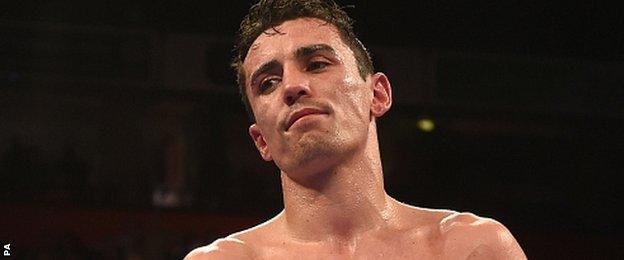

Anthony Crolla fractured his skull and broke an ankle attempting to tackle burglars

When you do something as dangerous as getting hit in the head for a living, you're more likely to be fatalistic than most 'normal' people. It is a boxer's innate sense of heroic fatalism that helps him recover when bad stuff happens. And it is the redemptive nature of boxing that film-makers love so much.

"I was lying in a Spanish hospital, next to a window, a red hot sun blasting my head," says Brook, who makes the first defence of his world title against Romania's Jo Jo Dan at Sheffield's Motorpoint Arena on 28 March.

"I wasn't able to move or speak to anyone. I remember looking down at my leg and thinking: 'A couple of weeks ago I was jumping about in a ring in California with the IBF belt. Now I'm not sure if I'll be able to walk again.' But what happened hasn't scarred me mentally. I've put it behind me."

Adds Ingle: "For three months Kell was in a dark place. But Kell has always been able to drag himself through those dark moments. He lets out a big sigh, trudges through it and doesn't look back."

For Hearn, Brook's predicament was a stark reminder that, in boxing, the best laid plans often go awry so spectacularly as to leave you gasping.

"We had a big party in Sheffield, everyone was absolutely buzzing," says Hearn. "The next day, Kell went on holiday. Three or four days later, I got the call from Dominic. I flew straight out there and when I first saw him he was semi-conscious with his leg up in the air. It looked like it had been eaten by a shark.

"He's a very good friend but also a client, so from a selfish point of view I was thinking: 'We've got ourselves a welterweight world champion, we've invested a lot of time, effort and money and now he's never going to fight again.'

Kell Brook factfile | |

|---|---|

Born | 3 May 1986, Sheffield, England |

Family | Lives with wife Lindsey and two-year-old daughter Nevaeh |

Connections | Promoted by Eddie Hearn, trained by Dominic Ingle |

Pro record | 33 fights (22 KOs), 33 wins |

Pro honours | British & IBF welterweight champion |

"He was just a kid in a bar having a drink, celebrating winning a world title. It would have been devastating if he hadn't had the chance to be what I believed he could be. But this has changed him. He's got a wife and kid and another one due any minute. It just takes some people a little bit longer [to mature] than others."

But as any fan of boxing will tell you, sensible lives are overrated. After all, if Jake LaMotta had lived a sensible life, Martin Scorsese wouldn't have been able to make Raging Bull,, external one of the greatest films about any subject ever made.

The dark matter that swirls around boxing is part of what makes it so compelling. Boxing is not always heartwarming or uplifting - it is often ugly and depressing. Which is why it tells us so much about life.

- Published28 January 2015

- Published28 January 2015

- Published28 January 2015

- Published28 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published22 January 2015

- Attribution

- Published4 September 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published17 August 2014

- Published13 September 2014

- Published11 June 2018