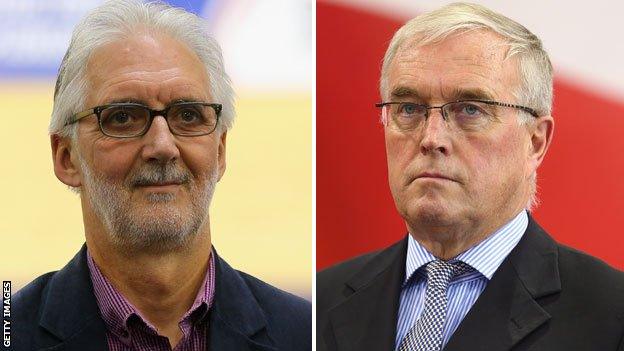

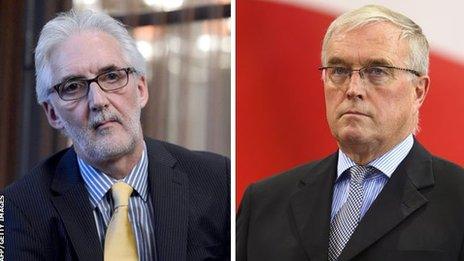

Brian Cookson and Pat McQuaid: Five questions for UCI rivals

- Published

Sport without rivalries is usually sport without a point. Remove the bite of competition and sport becomes exercise, or child's play with adult rules.

Take professional cycling, for example. Get rid of the disagreements, feuds and jealousies, and you are left with spin class with a more interesting view.

Cycling's narrative is so infused with tales of animosity that even its politics are feisty, as the current contest between Brian Cookson and Pat McQuaid for the right to run the sport is proving. It is a confrontation that has the bad blood of French greats Jacques Anquetil versus Raymond Poulidor, external, the personality clash of Italian rivals Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali, and the simmering resentment of the Blair-Brown government., external

Five-time Tour de France winner Anquetil had some memorable duels with Poulidor - but normally won

Rarely has a day passed recently without one of the duelling duo accusing the other of something dastardly. Most of the claims and counter-claims have been about the International Cycling Union's electoral rules - and there was a further development on Wednesday when McQuaid lost the support of the Swiss, one of the national federations nominating him for the election.

However, there are issues of more widespread interest at stake: what the sport must do to rebuild its doping-ravaged reputation, and how one of the world's most popular sports can become even bigger.

Over the last few weeks, I have interviewed both candidates. Here are five questions that set out the battle lines.

Q1: Both of you have been involved in the governance of cycling, on a national and international level, for some time. Do you feel any responsibility for Chris Froome and others having to repeatedly justify themselves against accusations of doping?

Current UCI president Pat McQuaid: No. Changing the culture of doping has been one of my big objectives (since taking charge in 2005).

It started with aggressive testing. We then brought in the "whereabouts" system and the biological passport, as well as a no-needles policy.

We also introduced a rule that said anybody who has had a corticosteroid injection must take eight days off, and another that said anybody who is caught doping is not allowed back into the entourage of the team.

At the same time, we've brought in stars like Mark Cavendish to talk to junior riders about supplements and good nutrition at the World Championships. We've also funded a pilot study with Lausanne University into the sociological causes of doping.

What happened in France is that the verdict in the Lance Armstrong affair is still fresh in people's minds. But the sport has moved on a huge amount; I think people should recognise that. The attitude of the riders is completely different now to what it was 10 years ago, and the science is different in terms of catching cheaters too.

So I think some of the media may have gone a little overboard and it was a bit unnecessary. Chris and the other riders deserve credit for what they're doing naturally.

Challenger and British Cycling president Brian Cookson: One of the reasons why we decided to have our own British professional team (Team Sky) was to protect young British riders.

British Cycling has always had a strong anti-doping policy. We've put in place an ethos to ensure we will be clean. So I'm as confident as I can be about British riders, the Great Britain team and Team Sky.

Cycling disfigured by doping - Cookson

I feel very sorry for Chris Froome because he has had to deal with the impact of being the first Tour winner since the Armstrong revelations. It is sad many people now respond to an outstanding performance by assuming it must be because of cheating, but we have got to tie that back to the UCI's lack of credibility.

Yes, progress has been made and the peloton is cleaner than it has been for years, but the UCI as an organisation has lost credibility because it has not done enough to resolve the problems of the past.

I cannot understand why the current leadership has spent so much time feuding with the very people who could be helping us restore our reputation. Why was the UCI arguing with the United States Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) about jurisdiction in the Armstrong case? Why was that the most important issue?

And I don't think we have got to the bottom of how doping issues were handled by the top level of the UCI over the last few years. Until we have a forensic investigation into the allegations of collusion and cover-ups the UCI will suffer. The UCI's own stakeholder consultation, run by Deloitte, told us that.

Q2: But you have, in the not-so-distant past, defended McQuaid's record as president. When did you decide cycling's reputation could only be restored by a change of leadership?

Cookson: I began to have serious doubts at the time of the Olympics in London when the UCI versus Usada jurisdiction row was kicking off; I really couldn't understand the line Pat McQuaid and his legal advisors were taking.

I pushed as hard as I could for the Usada verdict to be accepted, and that's what happened eventually. But the first I heard of that decision was at a press conference.

So I, as a member of the UCI's management committee, had no prior knowledge of what our position was going to be until I heard it like everybody else. That was one of the most important decisions in the UCI's history and the management committee wasn't even advised about it. I found that completely unacceptable.

Then we had the attempt to form an independent commission (into the Armstrong affair). That was something the management committee supported but there was huge concern at the model that was being proposed, again without consultation.

The whole thing cost a huge amount of money, without any authority from the management committee, and was then scrapped because the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) and others gave it no credibility. So it was a huge waste of money, solely on the president's say-so. That was the final straw.

But I did make a statement to support Pat, to help clear the air and move things along. That was at the beginning of this year. But since then things haven't improved, we haven't had better consultation, further mistakes have been made and the UCI's own consultation process made it clear we needed change.

It was at that point I decided to see if there was any support for me around the world to make some changes, and it seemed there was, so I decided to make a challenge.

Q3: I think even your harshest critics would acknowledge there has been some progress, but Armstrong's last win was eight years ago. Have you moved fast enough? Was part of the problem that you simply got too close to Armstrong?

McQuaid: It was a very dark era, and it wasn't just Armstrong. But we can only move as fast as the system will allow. The testing system has been created by Wada and we work within that, it's all we can do.

There's the now infamous story of the tests at the Tour de Suisse where (Armstrong's former team-mate) Floyd Landis claimed we buried a positive test. We have shown that that is not the case. There were two suspicious tests: you cannot declare a suspicious test positive.

So what do you do? We target-tested Armstrong immediately after and the results came back negative.

Bear in mind that there was no test for (blood-boosting drug) EPO at the start of Armstrong's career - they could all use it. We then introduced the test, so they started micro-dosing.

But now with the biological passport the situation is completely different. The blood profiles are built up over time and experts study them. We can either open up a process against a rider based on the passport, or we use an unusual profile to target-test.

Lance Armstrong was stripped of all his seven Tour de France wins by the UCI for doping

We spend $7.5m a year (£4.79m) on anti-doping. You don't spend that sort of money if you're not serious about catching cheats. What upsets me is that when we catch a cheat it becomes a rod to beat our backs. It should be 'good, they've caught another cheat, and he's out of the sport'.

And I don't agree that we got too close to Armstrong. It's only natural in any sport that the powers-that-be know the star athletes. Sepp Blatter would know Lionel Messi to say hello to. I know Fabian Cancellara, Phillippe Gilbert and Mark Cavendish to say hello to.

But it doesn't mean you drop your guard. If they need to be tested, you do it. We have caught stars. We caught Marco Pantani on the final day of the Giro d'Italia, external and threw him out of the race.

So it's not as if we're afraid to do that. Landis was caught under my presidency. But the result never came for us to catch Lance Armstrong.

Q4: So you have shown how tough you are against doping, why do you think you have struggled to get a nomination for re-election as UCI president? How do you feel about that?

McQuaid: It saddens me at times. But I left Ireland eight years ago and now work for federations across the world.

A movement against me was started on social media, and they generated a lot of support. The guys involved in cycling in Ireland now don't know me personally as they used to.

So that can get annoying, but I know what I'm trying to achieve. I know it's respected by the federations around the world, so I'll continue with my work.

Q5: The UCI's anti-doping record is clearly one of the biggest issues in this election, but it's not the only one. Your opponent is making much of his work to grow the sport outside Europe. What experience can you point to in this area?

Cookson: In the four years I have been a member of the UCI's management committee I was president of the cyclo-cross commission for two years and then took on the road commission, which looks after road racing below the elite level. I would say there has been pretty good progress there.

But over the last 16 years my main job has been president of British Cycling, and it's clear that there has been a corporate effort to transform the sport in Britain in every sense.

How does blood doping work?

We've had massive elite success, we've got one million more people riding regularly, 100 new clubs since the Olympics and a 50% increase in membership. I don't think I've done a bad job.

In terms of global cycling, I think there's huge potential to grow the sport, and I've been clear in my manifesto about my wish to grow women's cycling, which has been neglected, but equally to accelerate the growth in all forms of cycling in Africa, Asia and South America.

If you talk to people out there you'll find they've been starved of resources from the UCI. Africa has had a piddling amount of investment, yet that same UCI can find 2.25m CHF (£1.59m) to set up a commission that never even meets.

So it's not the case that (McQuaid) has had a major impact on the development of cycling around the world; in my view he has inhibited it.

What we need is knowledge exchange. We should be encouraging coaches from developed nations to visit developing nations, and the reverse. We could set up partnership arrangements between successful federations and smaller ones - British Cycling is doing that.

To me, that's a lot more valuable than sending developing nations a few bikes.

- Published21 August 2013

- Published7 August 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published4 September 2014

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published25 June 2013

- Published26 June 2013

- Published1 July 2013