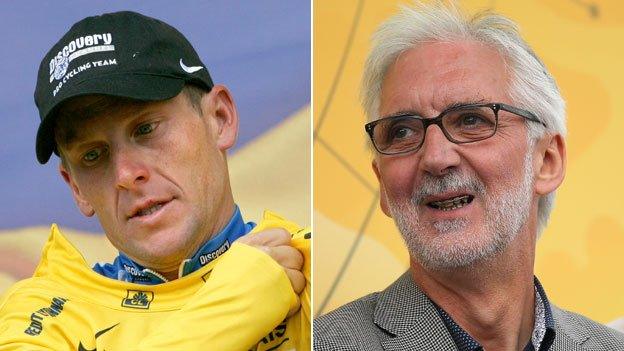

Lance Armstrong: From Paris to pariah to pardon?

- Published

Lance Armstrong passes the Arc de Triomphe on his way to a record seventh Tour de France title

They meet at his shop every week, buy his kit and drink his coffee, but most of the guys who have rolled up for the oldest group ride in Austin do not want to utter his name.

We are in the Juan Pelota Cafe, which is at one end of Mellow Johnny's, external bike shop. That is "Mellow Johnny" as in the French for yellow jersey, "maillot jaune"; and "Juan Pelota" as in "one" and the Spanish for "ball". Guess who?

"Have you read 'Seven Deadly Sins'?" Andrew, a member of the Violet Crown, external cycling crew, asks me, referring to the Irish journalist David Walsh's, external most recent Lance Armstrong expose.

"For me, he went from being complicated to evil."

I am tempted to ask if Andrew has read New York Times writer Juliet Macur's, external 'Cycle of Lies', too, as that has Armstrong starting evil and ending up deeper in hell than Satan, but we have got plenty of time to talk about the man who owns the shop we are standing in, what's the rush?

Minutes later, as advertised, our Sunday saunter, external has clipped in and we are pedalling off to somewhere approximately 25 miles away, the unseasonable sunshine warming our backs.

And then a funny thing happens. It turns out everybody does want to talk about 'Lance' after all.

More on the BBC's Armstrong exclusive | |

|---|---|

A couple of the guys used to race against him as a junior - "he was cocky but he could back it up" - and most of them had seen him out training on these roads - "he'd ride along for a while, chatting, and then say 'thanks for the tow' and shoot off".

They did not seem that upset about the doping - "they all did it…America loves a winner…who can say they wouldn't have done the same?" - but the "other stuff" was a problem.

Perhaps not an irredeemable one, though.

A week before, Austin had staged the US National Cyclo-cross Championships., external It should have been a celebration of the self-confident city's vibrant cycling culture, but when the final Sunday was nearly cancelled amid a row over possible damage to some old oak trees it ended up like an episode of Parks and Recreation., external

Armstrong was not present - he has not touched a bike since early November and tends to avoid gatherings these days, he can do without the "Hey, it's Lance! Wait, is that cool?" expressions on people's faces - but he knew this was important to the city he moved to as an ambitious teen, the city whose rise to national prominence he had once been synonymous with. So he made some calls.

Within hours the race was back on (his was not the only call), but on Monday. This meant a lot of people needed a room. Thankfully, Hotel Lance was open and within minutes of the tweet, external going out, half a dozen competitors and their families were sorted for the night, free of charge.

It was a small gesture but it resonated with Violet Crown's members, and over the next three and-a-half hours a more nuanced picture of Armstrong emerged.

Armstrong's Tour de France battles with Italian maverick Marco Pantani divided cycling fans but attracted huge television audiences - both were cheating, though

Nobody in the group, some of whom have been doing this for 30 years, tried to tell me he is a misunderstood saint, stitched up by jealous foreigners and sanctimonious officials, but then nobody told me he is an out-and-out bounder, either.

So when Armstrong agreed to meet the BBC to discuss a first television interview since Oprah Winfrey two years ago, I wondered which version of the paradoxical pedaller I would get.

Come on over, he said; there are direct flights between London and Austin, he pointed out; but "for everybody's sakes this isn't an interview", he warned.

The flight was interesting. Alex Gibney's "The Armstrong Lie", external on one channel; on another, the episode of "Veep", external when Julia Louis-Dreyfus's vice-president almost signs her name next to Lance Armstrong's on an IT company's graffiti wall ("we're having that one chemically expunged").

But when my taxi pulled up outside his house at 8am he was stood in the doorway, bare feet, in short-sleeved shirt and shorts, big smile, mug of coffee in his hand, Halloween decorations framing the door. Deflectors up, I went in.

Two hours later, we were outside his house in the road, him still barefoot, planning the rest of my day in Austin. A few neighbours strolled by, greeting him as they did. It was a very nice neighbourhood.

There was a time when many Americans wondered if Lance Armstrong would like to stand behind this lectern on a more full-time basis

We had both got what we wanted: the Beeb had its interview (without conditions) and he had shown me he was not a black hole of malignant energy.

Had I been played? Seduced by his famous charm, disarmed by his children, thrown off balance by his ability to laugh at himself?

Probably, but that went both ways. Did I really believe this interview could be a step towards rehabilitation? Maybe, but most of all I thought it would be a blockbuster.

The trail went cold after that meeting. As others have discovered, he compartmentalises his life better than a Boxtroll, so we were put aside until the right time.

For weeks we were left like his loyal band of followers, tracking his runs on Strava,, external deciphering his tweets.

Interviews with Golf Digest , externaland Rouleur , externalcame out (was he stringing us along?), and then an email arrived on Christmas Day: Le Boss says let's do it.

Most of you will have seen or heard bits of our sports editor Dan Roan's interview with Armstrong now, and it seems most of you have had your views of him (Lance, not Dan) reconfirmed.

Inevitably, most of the reaction has focused on the headline "I would do it again". He knew that would happen (he had market-tested it recently in audiences with students at Harvard , externaland property developers in Switzerland),, external so do not feel sorry for a misquoted victim of the nasty media.

But should we admit he has a point?

Everybody likes to think they are noble enough to find their way out of moral mazes, which is a surprise when you consider the evidence. As Armstrong put it, he does not know many who decided to forego the dream and keep their integrity.

Sure, there were some; but as French rider Christophe Bassons, one of the few good men, pointed out this week, he cannot remember many either.

These might be uncomfortable truths but Armstrong did not invent doping, they really were almost all at it, it did not stop after he quit, and the United States Anti-Doping Agency , externalprobably was guilty of hyperbole when it called US Postal's doping antics the "most sophisticated and professionalised" in history. They were undoubtedly "successful", though.

He is also on firm ground when he highlights the inconsistency of stripping his titles, whilst umpteen other dopers keep theirs, some of whom have lied just as hard and long as him.

Does this mean they should be returned? Well, he believes "history" will sort that out, and in the meantime he still has his "memories".

I suspect history will decide it has better things to do. Whether he has the titles, nobody has them, or a queue is formed behind the only podium-finisher from his era not to be caught cheating, Spain's Fernando Escartin, it does not matter. They are all tainted.

But what should Armstrong do with the rest of his life? Some want to put him in prison. House arrest will suffice for others.

This is where I believe he makes another reasonable point.

As you will see if you watch our documentary "Lance Armstrong: The Road Ahead" over the coming days on BBC News and World News, or BBC1 on Sunday, we visited the cancer charity formerly known as the Lance Armstrong Foundation.

When its founder went toxic two years ago, it dropped his name, sent his framed jerseys back and told him to stay away, something he describes as "the deepest cut".

Armstrong's cancer foundation teamed up with Nike to sell 90 million yellow wristbands. giving birth to a fashion statement that continues today

Livestrong,, external like its erstwhile patron, is not doing too badly on the face of it. It has lovely headquarters, in a cool part of town, and has just handed the University of Texas £30m to develop better cancer care.

But its revenues have fallen dramatically, Armstrong's corporate sponsors have slipped away and it is currently without a chief executive.

It seems to have lost its confidence and identity. Our requests for interviews were politely but firmly declined, as was the idea that we might film links in Livestrong's reception.

Armstrong, meanwhile, is on the other side of town desperate to help.

As outlined in Esquire's Armstrong profile, external last summer, the chastened campaigner continues to do good work in the cancer community.

I do not know if that work was accidentally-on-purpose leaked but I can say he was trying to persuade a frightened teenager to go ahead with treatment on the morning of our interview, and we would not have known that unless we directly asked his agent about it.

There will be some of you screaming now that Livestrong, the chugging with politicians and celebrities, and the entire cancer-survivor backstory was part of the con, a shield to justify the fraud in France.

But Armstrong really did survive life-threatening cancer and decide to do something positive afterwards. The result was £300m raised for a foundation that has helped three million people. That happened., external

Is it possible that some good can still come of the failed enterprise that was Lance: The Great American Hero?

His days of winning elite bike or triathlon races are almost certainly gone, and there should be no Hope Rides/Runs/Whatever Again hoopla in his future. But who benefits by stopping him from running "a slow marathon", external or perhaps even helping cycling's move to the mainstream again?

The wins still on Armstrong's record | |

|---|---|

Tour de France: 36th overall in 1995 & two stage wins (1993 & 1995) | |

La Fleche Wallonne: 1996 | |

Clasica de San Sebastian: 1995 | |

World road race champion: 1993 | |

US national champion: 1993 | |

Clearly, there needs to be some quid pro quo. Armstrong is quick to highlight the apologies that have been accepted, but less forthcoming on those he still has not tried hard enough to appease.

One idea might be to actually help the fight against doping today, instead of rationalising the dilemmas of yesterday.

Armstrong was the villain of a piece in USA Today , externallast week about the Taylor Hooton Foundation,, external a Texas-based organisation set up by a father who lost a teenage son to suicide after he got caught up in steroids at school.

The foundation now uses Armstrong's story to warn children about the perils of performance-enhancing drugs.

"Everyone we talk to knows Lance," Don Hooton told the paper. "There's never, ever, a positive reaction to him."

But what if Armstrong gave those talks? Might the reaction change and the impact be greater?

He will never again be the face of a major sponsor, be talked of as a future senator, or jet around the world performing miracles with the likes of Bill Clinton , externaland Bono,, external but there are enough people on Sunday morning rides and cancer wards still willing to give him another chance.

Perhaps the best of the library of books that Armstrong's modern morality tale inspired is "Wheelmen", external by Wall Street Journal reporters Reed Albergotti , externaland Vanessa O'Connell., external

The 43-year-old does not read books (he prefers newspapers), which is a shame because Wheelmen's final paragraph sums his situation up perfectly:

"He really does hold the keys to his own redemption. Whether he will use them, for the sake of both his soul and the soul of the sport he once loved so much, remains to be seen," they wrote.

"He is a man of great strength, determination, and resilience, and we truly hope that he will use those qualities to make a moral comeback as complete as the physical comeback he effected from the cancer that nearly killed him. Time will tell."

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015