UCI report into doping shames cycling as it lays bare darkest sins

- Published

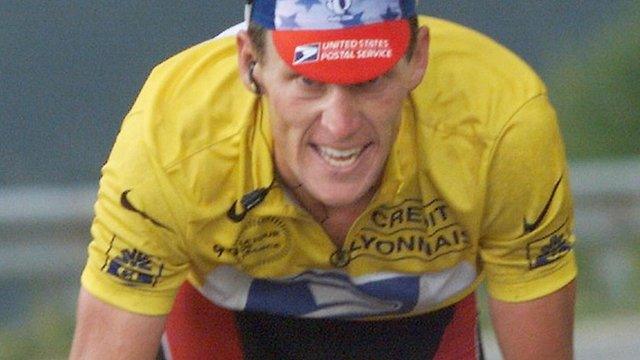

Lance Armstrong is interviewed by BBC sports editor Dan Roan

Last month, Brian Cookson warned that the Cycling Independent Reform Commission report into doping would make for highly unpleasant reading.

The president of cycling's world governing body - and thus the most powerful man in his sport - wasn't wrong.

The report lays bare cycling's sins in forensic detail.

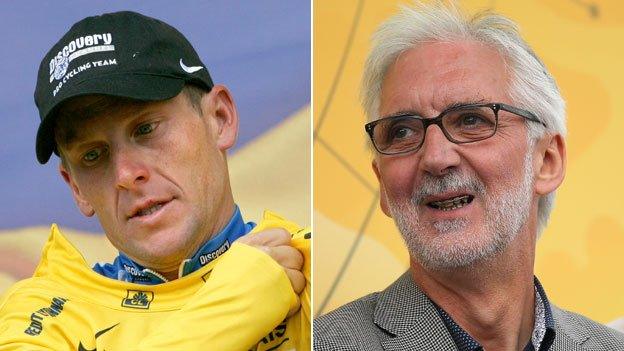

Hein Verbruggen and Pat McQuaid, Cookson's predecessors in charge of the International Cycling Union (UCI), may have been cleared of the worst allegations of corruption - and therefore feel vindicated - but they are not spared a withering critique of their leadership.

They are shown to have presided over a catastrophic episode of events that left cycling's credibility in tatters.

The findings reflect dreadfully on both men, pointing to a lack of governance, transparency and prudence when they were at the top of the sport and effectively accusing them of turning a blind eye to the extent of the doping by Lance Armstrong and others.

Unforgivably, there was more emphasis placed on managing the image of cycling rather than ridding the sport of problems.

Armstrong on drugs, history and the future

Many readers, for example, will be horrified by the "temporal link" between McQuaid's "sudden U-turn" that allowed Armstrong to return from retirement 13 days early to participate in the 2009 Tour Down Under despite not having been in the UCI testing pool for the prescribed period of time, and "the decision of Armstrong, which was notified to McQuaid later that same day, to participate in the Tour of Ireland, an event run by people known to McQuaid".

They will be equally staggered to learn that the UCI, together with the Armstrong team, became directly and heavily involved in the drafting of the Vrijman report.

The report was commissioned by the UCI to investigate accusations that, in 2005, Armstrong tested positive for EPO during the 1999 Tour de France.

According to Circ: "The main goal was to ensure that the report reflected UCI's and Lance Armstrong's personal conclusions... UCI had no intention of pursuing an independent report."

These findings - and others - are damning, painting a terrible picture of an entire sport in thrall to money and its influence.

From sponsors who turned a blind eye to riders getting preferential treatment because of their commercial pull and teams drawn to cheat because of the rewards, not to mention a governing body that bent its own rules, undermining the very fight against doping that it had a responsibility to lead.

This wasn't just about winning, it was an ugly, systemic understanding in which many were complicit.

It feels significant that US anti-doping chief Travis Tygart, the man who pursued and brought down Armstrong, says his organisation "will work with the current UCI leadership to obtain the evidence of this sordid incident to ensure that all anti-doping rule violations related to this conduct are fully investigated and prosecuted, where possible".

The International Olympic Committee will also be interested in the Circ report given Verbruggen is an honorary member of the IOC.

'A culture of doping continues to exist'

Furthermore, when it comes to the current state of cycling, the report pulls no punches. It will come as something of a shock to those who assumed the downfall of Armstrong - and lack of major doping crises in recent years - meant the sport had been healed.

We are told that, while the situation has undoubtedly improved, a culture of doping continues to exist in the sport and "a number" of riders "continue to cheat".

It refers to "one respected cycling professional" who felt that "even today, 90% of the peloton was doping". Circ found "doping in amateur cycling is becoming endemic", too.

Circ also heard that riders:

Are using ozone therapy, which involves extracting blood, treating it with ozone and injecting it back into the blood;

Continue to use steroids;

That it is still possible for riders to micro-dose using EPO without getting caught;

And that abuse of TUEs (Therapeutic Use Exemptions) is "a significant problem" today.

The report recommends night-time testing and urges the UCI to set up an independent whistleblower desk.

Much for the professional riders to consider, as they race from for Saint-Remy-les-Chevreuse to Contres on Monday on the second day of this year's Paris-Nice.

So much for cycling's new, clean era. The findings certainly suggest the recent anti-doping infringements by the Astana team are far from being a one-off.

Circ also found that doping occurs in women's cycling and "was given examples where riders in the sport had been exploited financially and even allegedly sexually".

The panel was also told of well-known "doping doctors", still operating in the sport today, and that "a number of knowledgeable and reliable people... were of the view that there is an elite who are still doping in a sophisticated way today".

But who are they? Frustratingly, the report does not tell us.

A missed opportunity?

Clearly cycling has no room for complacency and Cookson will argue this honest appraisal of the challenges that remain proves the sport has learnt some hard lessons.

However, for many, the report will be a letdown, a missed opportunity, telling us little we didn't already know or at least strongly suspect.

So much has already been written, admitted and discovered about cycling's toxic past, very little now surprises us.

It is understandable, therefore, if many critics are disappointed the report contains no new names or explicit, major revelations. The focus is inevitably on Armstrong, but, as he told me when I interviewed him in January, cycling's problems went well beyond him.

In a statement, Elliot Peters, Armstrong's attorney, told us: "Lance Armstrong co-operated fully with Circ... we applaud Circ for taking a courageous and unvarnished look at the truth.

"In the rush to vilify Lance, many of the other equally culpable participants have been allowed to escape scrutiny, much less sanction, and many of the anti-doping 'enforcers' have chosen to grandstand at Lance's expense rather than truly search for the truth."

As the report's authors admit, no rider voluntarily admitted an anti-doping rule violation, while several people, including riders, scientists, ex-riders and former UCI staff members, refused to be interviewed.

The panel of Dr Dick Marty, Peter Nicholson and Professor Ulrich Haas interviewed 174 people, including Armstrong and Chris Froome, and spent €3m (£2.16m) during their investigation, so this was a very serious process.

Crucially, though, they had no power to force people to attend interviews.

It will raise questions, therefore, over whether this really can draw a line in the sand and be the moment when cycling truly comes clean - that Cookson needs it to be if he is actually going to repair cycling.

As Cookson himself said last month: "I don't think there will be a lot of new revelations, because mostly we have a good idea of what was happening and how widespread the problems were." Quite.

'Riders still reluctant to report doping'

For some, the report will be an underwhelming and ineffectual gesture, only serving to demonstrate that the "omerta" - cycling's code of silence - lives on.

As the report admits: "Although the influence of the classic omerta has declined, riders are still reluctant to report doping or suspicious conduct to the authorities."

Cycling must be credible - Sir Dave Brailsford

Dispiriting stuff.

Others, however, will be more generous in their assessments, deciding that this is just what cycling needs; an honest appraisal of the past and the present and offering recommendations for the future.

They will give credit to the UCI for being transparent about this report, in a way Fifa, football's world governing body, failed to over the Garcia investigation into allegations of corruption. For example, there are surprisingly few redactions.

They will be encouraged by the courage required to conduct an unprecedented account of what happens when a sport completely loses its way.

'Other sports must take note'

The report concludes that "there is no straightforward solution to the problem of doping in cycling" and that "one important message that UCI and all stakeholders must keep to the fore is that the fight against doping is a continual process".

If cycling can remember this at all times, this process will have been worthwhile.

Sport cannot stand by, hold its nose and pretend this is just about cycling. Few escape the spectre of doping. Take, for example, athletics, American football, baseball, rugby and weightlifting.

What is certain is that the Circ report should be studied by every sport, because while cycling is still clearly in a critical condition, it at least knows it is ill.

This must embolden leaders in all sports to push again in testing, research, education and above all good governance. The report is of value to that extent, but it makes for deflating reading.

- Published8 March 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published5 March 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015