Doping culture in cycling 'still exists' according to Circ report

- Published

The report says: "Numerous examples have been identified showing that UCI leadership defended or protected Lance Armstrong and took decisions because they were favourable to him"

Cycling continues to struggle with widespread doping, according to a landmark report into the sport's troubled recent history.

Set up last January to investigate how cycling so badly lost its way during the 1990s and 2000s, the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (Circ) has heavily criticised the sport's leadership throughout that era.

Its 227-page report, published on Monday, clears the International Cycling Union's (UCI) bosses of outright corruption but censures them for a litany of failings.

Foremost among these are that the UCI did not really want to catch cheats and therefore turned a blind eye to anything but the worst excesses.

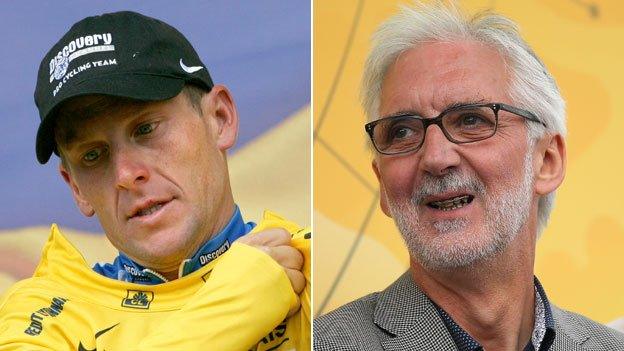

The report's authors also accuse former UCI presidents Hein Verbruggen and Pat McQuaid of failing to follow their own anti-doping rules and showing preferential treatment to disgraced former champion Lance Armstrong.

A total of 174 anti-doping experts, officials, riders and other interested parties were interviewed. These are the main points:

One "respected cycling professional" believes that 90% of the peloton is still doping, another put it at 20%

Riders are micro-dosing, taking small but regular amounts of a banned substance, to fool the latest detection methods

The abuse of Therapeutic Use Exemptions, sick notes, is commonplace, with one rider saying 90% of these are used to boost performance

The use of weight-loss drugs, experimental medicine and powerful painkillers is widespread, leading to eating disorders, depression and even crashes

With doping done now on a more conservative basis, other forms of cheating are on the rise, particularly related to bikes and equipment

Doping in amateur cycling is endemic

The €3m (£2.16m) report was compiled by chairman Dr Dick Marty, a former Swiss prosecutor, and two vice-chairs, German anti-doping expert Professor Ulrich Haas and Peter Nicholson, an Australian who has investigated international terrorism and war crimes.

UCI president Brian Cookson, who swept into office in 2013 promising a fresh start for an organisation that had been badly damaged by its close links to Armstrong, thanked the panel for its work and did not try to sugar-coat its findings.

"It is clear that in the past the UCI suffered severely from a lack of good governance with individuals taking crucial decisions alone," said Cookson.

"Many [of these decisions] undermined anti-doping efforts; put the UCI in an extraordinary position of proximity to certain riders; and wasted a lot of its time and resources in open conflict with organisations such as the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) and US Anti-Doping Agency (Usada)."

Cookson added that his predecessors and their close associates regularly interfered in anti-doping cases which "served to erode confidence in the UCI and the sport".

Siege mentality and a fallen hero

The issues that Cookson is referring to are dealt with over 120 pages of forensic detail.

The report explains how a sport that had always taken a lenient approach to doping, and had an entrenched, Mafia-like culture of "omerta" when it came to not talking about doping, entered a new phase when the "game-changing" blood-boosting drug EPO became readily available in the early 1990s.

With no test for it until 2000 and performance benefits of 10-15%, it did not take long before almost everybody in the sport was using it. As the report says, "it would have been hard to overestimate the prevalence of drug use in the peloton" at this time.

BBC sports editor Dan Roan |

|---|

"The report should be studied by every sport, because while cycling is still clearly in a critical condition, it at least knows it is ill" |

Read Dan Roan's full analysis of the Circ report |

Numerous interviewees told Circ the UCI's view was it should only try to contain the problem and make sure the riders did not kill themselves, and that actually catching cheats was bad for the sport's reputation.

It was against this backdrop that Verbruggen took control of what had been an insignificant governing body and turned it into a far larger and more ambitious entity.

According to the report, the Dutchman had almost dictatorial powers at the UCI between 1991 and 2005, and continued to exert influence under the reign of his hand-picked successor, Irishman McQuaid.

The pair will be relieved to have been cleared of the most serious allegations against them, namely that they were bribed by Armstrong to cover up positive tests in 2001; and that he paid for what was meant to be an independent report commissioned by the UCI to investigate reports he had tested positive during the 1999 Tour de France.

Armstrong on drugs, history and the future

But Circ did not spare them on a number of glaring errors of judgement and examples of poor governance:

World champion Laurent Brochard in 1997 and Armstrong in 1999 were both allowed to backdate medical prescriptions to avoid sanctions, a clear breach of the anti-doping rules

McQuaid abruptly and unilaterally changed his mind to allow Armstrong to ride at the 2009 Tour Down Under despite not being available for testing for the required six months beforehand. At the same time it was announced that Armstrong would later that season ride in the Tour of Ireland, an event organised by what is described in the report as "people known to McQuaid"

While Armstrong did not pay for the 2006 report into his alleged positive tests at the 1999 Tour, his lawyers did draft large sections of it, along with senior UCI staff desperate to shift blame away from the rider and onto the laboratory that leaked the results and Wada

The UCI asked for and accepted two large donations from Armstrong, and enquired about a more regular gift as late as 2008

Repeatedly came out to defend Armstrong against accusations of cheating, supporting him in two high-profile legal cases

There is also considerable criticism of the UCI's cost controls, ethics procedures and electoral practices, with Verbruggen and McQuaid accused of breaches of the rules in the 2005 and 2013 elections.

The Lance Armstrong story | |

|---|---|

Born: Plano, Texas on 18 September 1971 | |

Tour de France victories: 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 (22 individual stage wins) - all have been stripped from his record | |

World Championships road race victory: 1993 | |

Cancer survivor: Diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996. The disease spreads through his body. Launches Lance Armstrong Foundation for Cancer. Declared cancer-free in 1997 after brain surgery and chemotherapy | |

Retirement: Announces he will retire after the 2005 Tour de France, which he wins. Angered by drug allegations against him, Armstrong announces in September 2008 he will return to professional cycling. In June 2010, he reveals via Twitter that the 2010 Tour de France will be his last. On 16 February 2011, Armstrong announces retirement again. |

Both men have reacted by welcoming the report's central finding that there is no evidence of corruption or direct collusion in any of the numerous doping scandals that beset the sport on their watch, with Verbruggen telling the BBC: "How can I be annoyed about being cleared of cover-ups and bribes?"

He added that it is "so easy to rewrite history 25 years later".

One man who would dearly love to rewrite history is Armstrong, who told the BBC last month he hoped his two interviews with Circ would lead to the panel recommending a reduction in his lifetime ban from almost all organised sport.

The former icon will be bitterly disappointed, then, that Circ has not exercised its right to ask Usada to reconsider its sanction, despite noting on more than one occasion that his treatment is inconsistent with almost every other member of his team, not to mention the vast majority of riders he competed against.

Armstrong told the BBC he was "grateful" to Circ for letting him help with the report and said he was "deeply sorry for many things I have done".

The job is never done

While many senior figures within the sport will be feeling very bruised by the report's assessment of what happened during the EPO era, Circ did acknowledge the huge improvements made in the anti-doping effort, particularly after 2006.

It noted a far more aggressive approach to catching cheats, greater investment in anti-doping and the early adoption of the biological passport, the most effective tool in the fight against cheats since the EPO test was introduced in 2000.

Lance Armstrong admits doping to win cycling titles

But the interviewees also made it clear that doping had not been eradicated.

The report listed dozens of substances and cutting-edge doping methods that riders are still believed to use. It also noted that teams do not know where their riders are training at all times, or with whom they are training.

The ready availability and falling costs of doping products is also flagged up as a huge concern, as is the continuing involvement of a number of unethical doctors.

The report concludes with a raft of recommendations to help prevent cycling from ever returning to the dark days of a decade ago, with ideas such as centralised pharmacies at races, a powerful riders' union, a greater push to encourage whistleblowing and more testing done overnight to catch micro-dosers.

- Published8 March 2015

- Published5 March 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published4 September 2014

- Published19 July 2016