Tour de France 2017: Is Chris Froome Britain's least loved great sportsman?

- Published

- comments

Polite rather than extrovert but no cycling robot - why is Chris Froome not more widely admired?

Bearing in mind that it took 110 years for the first Briton to win a Tour de France, you'd expect the man who then wins four of the next five to be one of the most loved and admired sportsmen of this or any other era.

There is no fluking a yellow jersey. Three weeks of physical attrition, of relentless mental calculations and stress, of staying ahead of a shifting mass of rivals ganging up to unseat you, of managing egos and efforts within your own team, of high mountains and cruel cross-winds.

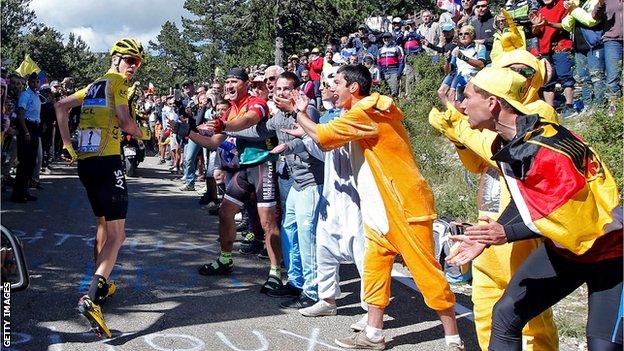

And yet when Chris Froome won his third Tour last year, having run up Mont Ventoux in his cleats on his way to victory, he failed to even make the 16-strong shortlist for the BBC's Sports Personality of the Year.

In case you want to blame the host broadcaster, it is worth remembering that in addition to the three BBC representatives on the selection panel there were former sporting greats Ryan Giggs, Victoria Pendleton and Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson; sports presenter Ore Oduba, writers Amy Lawrence and Liz Nicholl, chief executive of UK Sport; David James (sports editor of the Sunday Mirror and Sunday People), Adam Sills (sports editor of the Daily and Sunday Telegraph) and the Mail on Sunday's Alison Kervin.

That is a pretty wide cross-section of the sport-obsessed. It was also in an Olympic and Paralympic year. But 2015, when Froome became the first Briton to win the Tour twice, was not. He still came seventh in the eventual public vote, with just 3.86% of the total votes cast.

In 2013 he finished sixth with 5.2% of the vote. This after a five-year period when British male cyclists - Chris Hoy, Mark Cavendish and Bradley Wiggins - had won SPOTY three times between them.

Froome is not a man to bemoan his lot. Yet as he rides into Paris in yellow once again, having survived multiple challenges in one of the most competitive and ferocious Tours in memory, you could forgive him wondering what else he must do to be as cherished as some who have achieved significantly less.

There was certainly a shadow cast at the start of his reign by the success of Wiggins, the Neil Armstrong to his Buzz Aldrin. The second man on the moon will never enjoy the instinctive adoration as the first. There was the perception too, unfair though it may have been, that on the stage to La Toussuire during Wiggins' coronation in 2012, Froome had at least considered regicide if not tried to commit it.

Chris Froome was famously called back to help out team leader Bradley Wiggins during the 2012 Tour

It explains a slow start to his dance with the British public. But now, when his own Tour deeds have thrown Wiggins' achievements into stark relief, when the revelations about his former team-mate's therapeutic use exemptions have made some place a mental asterisk next to his win?

Only four other men in history have won three yellow jerseys in a row before. Each of them is a giant of the sport: Louison Bobet, Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Miguel Indurain. Only the last three of them and Bernard Hinault have won four or more in total.

If you do not appreciate Froome now, you probably never will. If the Champs-Elysees this Sunday doesn't make you relish what he has done and sense it in its proper context, you may also be missing out.

"Just to complete the Tour is hard enough," says Geraint Thomas, his team-mate first at Barloworld almost a decade ago and with Sky in the garlanded years since.

"Just to physically get round 3,000-odd kilometres of mountains, sprints, wind and rain, the pressure you're under - you have to be on top of your game to get through it. To win it takes a whole new level, and to win it multiple times, year in, year out hitting that same level, is super impressive.

"The training to even get there is full-on. Chris lives and breathes it from November all the way through to the following October. There is a lot of time away from his young family, a lot of training camps, on top of a volcano in Tenerife, hour after hour of hard graft.

Assuming Chris Froome secures his fourth Tour de France win, only four men will have more victories in the race - Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault and Miguel Indurain won five times each

"And it's not just the training - it's living the right way. The mental discipline is just as hard as the physical work. I do the training and I enjoy it. That's the easy part.

"It's when you're at home and you're starving hungry and you want to pig out but can't, when tea is quinoa rather than the massive pizza you'd really like. You go out with your partner and she will have a glass of wine or a dessert, or she orders a steak and you have to settle for a piece of steamed fish. Chris lives like that throughout the year."

Wiggins was a great stylist on his bike, smooth on the pedals, a track rider's instinctive handling skills. Froome is all elbows and effort, grimacing up mountains, descending like the last few frames before an almighty pile-up.

If that has kept the aesthetes cool towards him, the struggling amateurs can understand both the determination and the improvement it has brought. Wiggins could be wonderful company for his team-mates, but he could also be moody and introverted. Froome has grown into the role of team alpha male, learning from his predecessor, managing all the messy stuff that comes with the leader's jersey.

"Being in yellow takes at least half an hour away from your recovery every day," says Thomas, who spent four days on top of the GC standings this month.

"You finish the stage, you try to do your warm-down, then it's on to the podium, and that's the good bit. Then you have to do TV and radio, and you get asked the same two questions 15 times, which gets quite monotonous when you're already so tired.

"You then speak to the print media, you go into another press conference, and then doping control. If you can get the job done in doping control you can be in and out in 10 minutes. If it's been a hot day and you're dehydrated, you can be in there for an hour. All the other guys will be straight onto the team bus to do their warm-down, get some food down them and put their feet up.

"You get booed a lot. And it can be intimidating on those mountain roads. It's not like football, when the spectators can abuse you but not actually touch you. On those big climbs on the open roads, you never know. They could hit you; riders in our team have been punched before. It's another challenge."

Chris Froome's Tour wins have not been without their dramatic moments - here he is seen running up Ventoux after a bike issue in 2016

Froome is restrained in his public utterances, polite rather than extrovert. But he is no cycling robot. There is a back story which should both amaze and endear: growing up in Kenya with rock pythons for pets, spending long weeks in a small corrugated iron hut, with no running water and only a long-drop toilet, in a small village high in the red-dirt hills of Kenya's Rift Valley, the only white kid for miles around; getting knocked off by his own mother in his first race, aged 13; entering himself in his first world championships after borrowing the email account of the head of Kenyan cycling.

There is quirk and there is humour. Thomas tells a story from the pair's younger days when they were preparing for the national championships by staying at his girlfriend's parents' house.

Two nights before the race, Froome insisted on making everyone a potent Kenyan cocktail called a dawa. Except the ones he made for his team-mate were both more numerous and significantly stronger. He ended up beating his host by 10 enfeebled seconds.

Froome's prize sheet |

|---|

Tour de France general classification - 2013, 2015 and 2016 |

Tour de France mountains classification - 2015 |

Tour de France stage wins - seven |

Vuelta a Espana stage wins - four (three individual and one team time trial) |

Olympic medals - two (time trial bronze at London 2012 and Rio 2016) |

Made an OBE for services to cycling in 2015 |

Criterium du Dauphine titles - 2013, 2015 and 2016 |

Tour de Romandie titles - 2013 and 2014 |

There was also an engaging naivety. "Sometimes he had no idea about other riders," remembers Thomas.

"'Who was that guy? He looked strong today.' 'Yeah mate, that was Nibali. Only someone who's won every Grand Tour there is to win…'

"He's still like that now. Someone can switch teams and it will fool him. 'Who's that in the Trek jersey? He's quick!' 'Mate, that's Contador…'"

Sky's organisational and ethical struggles since the first revelations 10 months ago about Wiggins' use of the corticosteroid triamcinolone have both damaged the brand and leaked into the image of its other riders, no matter how removed from it some were.

Froome too will always have the unconverted in his congregation, unwilling to accept his improvement over the past seven years nor the explanation that blood parasite bilharzia was to blame for his previous inconsistencies.

Geraint Thomas has ridden loyally and brilliantly for Chris Froome - the Welshman reckons his team-mate is up with the very best of British cyclists

Then there is how British or not he is perceived to be, born in Nairobi, schooled in South Africa, resident now in Monaco, although it is not a unique story; Wiggins was born in Belgium to an Australian father, former England cricket captain Andrew Strauss spent his early years in Johannesburg and England rugby union captain Dylan Hartley was born and raised in Rotorua, New Zealand. Jenson Button and Lewis Hamilton also live in Monaco.

"I'd lived in Kenya but I didn't feel Kenyan," Froome told me after his first Tour win. "I'm British, with a British passport from birth."

English cricketing darlings Colin Cowdrey and Ted Dexter were born in Bangalore and Milan respectively. The first man to win a medal for Great Britain at a modern Olympics, way back in 1896, was Charles Gmelin, born in Krishnagar, India. Terry Butcher, the epitome of blood-soaked, badge-kissing Englishness, was born in Singapore.

You can pick your own path through that debate. What is unarguable is the manner in which Froome has won his Tours - with a solo attack at the top of Ventoux, with an ambush attack on the descent of the Col de Peyresourde, with an audacious uphill escape at the end of stage 14 this time around, having also ridden through picnics and survived a broken rear wheel.

Two years ago he had urine thrown at him by one spectator. He has been spat on. On this Tour he was jeered by partisan supporters of home favourite Romain Bardet. His composure has survived all that, with even French journalists who were charmed enough by Wiggins to dub him "Le Gentleman" coming round from acceptance to admiration.

"Cav is like the Muhammad Ali of cycling," says Thomas. "He's so close to Merckx's record for stage wins at the Tour.

"Brad had so much variety in all he achieved, Sir Chris did things no British rider had ever done before. It's so hard to compare across the different disciplines, but Froomey is right up there with them. He's not behind any of them."

- Published22 July 2017

- Published22 July 2017

- Published23 July 2017