Chris Froome wins Vuelta: 'A friendly accountant off the bike, a cold-eyed winner on it'

- Published

- comments

Froome will win his fifth Grand Tour title in Madrid on Sunday

There was a time, as recently as the start of July, when many in cycling wondered whether Chris Froome might not be what he was: not a single win all year, fewer days racing going in to the Tour de France than ever before, his rivals, many younger and in punchier form, lining up on his wheel.

Three months on, having bagged his fourth Tour and become the first Briton in history to win the Vuelta a Espana, they have been proved right. Froome is not the rider he was. He is a superior one.

When sporting success comes as frequently and in such dominant fashion as this it can be easy to assume it also came easily. A yellow jersey one month, a red the next, towed up the road by a line of Sky team-mates in white or black.

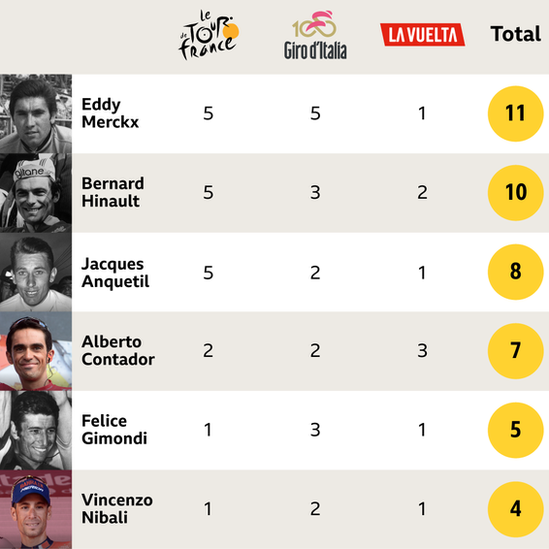

Even for a remarkable rider like Froome this double is an exceptional achievement. Only two Frenchmen, Jacques Anquetil in 1963 and Bernard Hinault 15 years later, have pulled it off before.

Froome said he had "unfinished business" before starting this year's Tour of Spain

He has done it in a style all of his own. Eddy Merckx, arguably the greatest cyclist of them all, was nicknamed The Cannibal for his insatiable hunger for wins, chewing up his rivals, ravenous whether the race was Grand Tour or little spin.

Froome, the serial winner - polite and friendly off his bike, as aggressive as an accountant - is transformed in the racing frenzy into a cold-eyed killer of others' ambitions, taking them out one by one, never with a single blow but the slow accumulation of pressure until they can take no more.

Anquetil loved the solo attack. Hinault stamped his mood and judgement all over the peloton. Merckx would take them anywhere he could - rampaging up mountains, tearing through time-trials, sprinting and always fighting, fighting.

Froome does it by stealth. A few seconds here, a few more there. A late push up a steep summit finish, squeezing out a little more on a solo ride against the clock.

It is not spectacular but it is brutal, a cruel constriction of his rivals, the inexorable application of a superior strength.

By the end of the Tour de France the other principal contenders for the general classification - Fabio Aru, Rigoberto Uran, Romain Bardet - were reduced to scrapping among each other for distant second. In this Vuelta it has been the same. His rivals start the race thinking what a nice chap Froome is and finish it having nightmares about him.

On Saturday, on arguably the most brutal climb in cycling, in conditions so grim that northern Spain in early September felt more like the north of Scotland in mid-November, he gave one final demonstration of all that has brought him so far.

Anquetil and Hinault never had to go up a mountain like this. The Alto de l'Angliru was a cattle track until the start of this century. Even now the tarmac hangs on to the mountain for dear life.

It is not the height. There are bigger climbs than its 1,573 metres. At 12.5km it is long but not endless. Its average gradient of 10% appears spiteful but not exceptional.

It is the ramps that break men - sections at 15% and 17%, the sort of thing a club cyclist struggles to keep moving on, then inhumane segments of almost 24%, less a route to the summit than a wet grey wall.

Riding up 15% makes your heart feel like it is jumping out of your chest; 24% makes you want to pick your bike up and throw it back down the cruel slopes.

To drive up it in Saturday's black cloud and thundering rain was nightmarish - a relentless steepness, brutal ramped hairpins, the smell of burning clutch acid in the nostrils.

Cycling up it appeared to make no sense. "What's the point of riding up a mountain that it would be quicker to go up by foot?" fumed the Italian Marzio Bruseghin after being pummelled by it nine years ago.

A vindictive mountain, so cold even watching that you wore all the clothes you had in your suitcase simultaneously, transformed by Froome into the peak of the British sporting summer.

It was Anquetil's burden that he was not loved as much as Raymond Poulidor, the eternal second place to his first. A greater tranche of the French public found it easier to empathise with Poulidor's obvious exertions and the limited reward they brought.

Froome too has struggled to win over his own sporting public in the same way as Bradley Wiggins, the first Briton to win the Tour. By rights, the past nine weeks should correct that curious imbalance.

Froome has been backed once again this summer by the dominant team in the peloton. Wout Poels, Mikel Nieve and Gianni Moscon have provided the same peerless support for him in August and September as Mikel Landa, Sergio Henao and Michal Kwiatkowski did in July.

He has also triumphed in a more competitive landscape. Anquetil had 12 other teams to contend with at the 1963 Tour and eight at the Vuelta. Hinault came up against 10 others in France and nine at the Vuelta. Froome has had to compete with 21 squads of nine riders at both the Tour and Vuelta.

Both Anquetil and Hinault won their own doubles when the Vuelta was held in April. Marshalling finite reserves of energy across spring and then mid-summer is arguably marginally easier than attempting to do the same from mid-summer to late summer. There were only 26 days between the Tour ending in Paris this year and the Vuelta beginning in Nimes.

Froome needs to win the Giro d'Italia if he wants to join the riders to have won all three Grand Tours

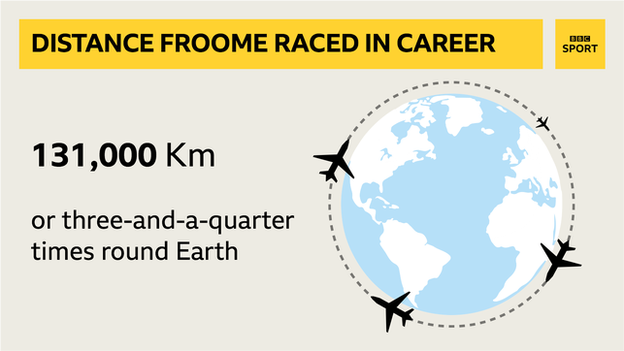

It is not just the physical exertion, but also the mental. Across his two Grand Tours Froome has raced for more than 4,200 miles, across 42 stages, through six countries, in blazing heat and pouring rain, all of it with opponents waiting to pounce on the slightest lapse of concentration.

He was in the leader's jersey for most of that, with news conferences to do every day, meaning he often leaves a finish more than an hour after his team-mates, eating later, resting less, the expectation going ahead of him and the pressure waiting for him on every new morning's start line.

No blow-outs after Paris, no allowing himself a week of cold lager or chips or even steak after three weeks of Gallic torment.

Anquetil used to take a glass of red wine with his main course during races, let alone the dessert and post-prandial cigar outside his competition schedule. Froome has been on steamed fish and wilted greens and a rumbling tummy for day after sapping day.

After more than 160 hours of racing this summer his final combined margin of victory will be just over three minutes.

It sounds like a small divide between him and rest. Do not be fooled.

- Published9 September 2017