Gino Bartali: How a cyclist's key work saved lives

- Published

"I want to be remembered for my sporting achievements. Real heroes are others, those who have suffered in their soul, in their heart, in their spirit, in their mind, for their loved ones. Those are the real heroes. I'm just a cyclist."

The world has been plunged into a pandemic. There are no sporting events for now, and governing bodies are working tirelessly to find a new time to get the show on the road - as our key workers battle to help saves lives.

Everyone else, athletes and non-athletes alike, have found themselves with time on their hands...

On this day 20 years ago, the iconic Italian cyclist Gino Bartali died of a heart attack. Nearly 80 years ago, the three-time Giro d'Italia and two-time Tour de France champion, too, found himself with time on his hands after cycling's biggest events were interrupted by World War Two. The Giro was on a five-year hiatus, Le Tour on a seven-year break. It robbed him of his best years in racing.

Instead, Bartali saved the lives of more than 800 people - information which only came to light in the years following his death. This is how he did it.

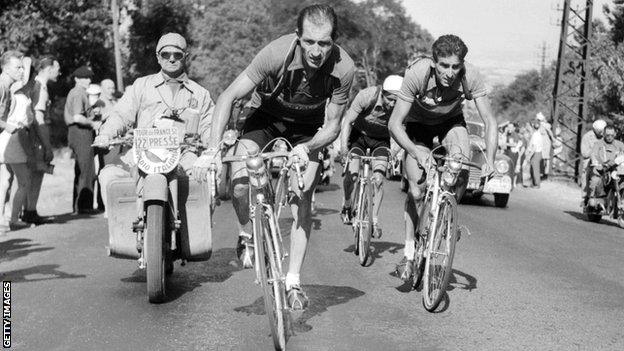

Bartali and Fausto Coppi (right) - great rivals on the bike, opposing roles in war time

Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer

Bartali remains one of cycling's most heroic riders, and was fabled to be the second most popular man at the time in Italy after Benito Mussolini, the leader of Italy's fascist party, following his first Tour de France win in 1938 - although the two were quite dissimilar.

But it was a bad time to be a professional cyclist in the era of Mussolini, particularly one who didn't want to get involved with politics.

In the 1940 Giro d'Italia, the final one before the event was halted, Bartali was introduced to a man who would become his fiercest rival, Fausto Coppi - a skinny 20-year-old who came from a family of farmers in rural northern Italy.

The rivalry began when Coppi was bumped from domestique duties to team leader after champion Bartali suffered with his injuries from a collision with a dog on stage two.

Coppi shocked the peloton by taking the Maglia Rosa (pink leader's jersey) during his first grand tour. But the big mountains in the Dolomites were yet to come. On Stage 16 Bartali found Coppi on the side of the road suffering with stomach problems.

A humble Bartali coaxed him back on his bike, convincing his team-mate and rival to continue. Success. The pair motored through the Dolomites tearing up the unforgivable mountainous terrain and teamed up for the remainder of the race with Bartali taking two stage wins and the overall King of The Mountains jersey, easing Coppi to overall victory with a lead of two minutes and 40 seconds.

"Some medals are made to hang on the soul, not the jacket," he once said, albeit in different circumstances - but it is a fitting sentiment to helping his rival and being graceful in defeat.

Don't look now: Bartali risked his life to deliver false documents on training rides and defy the Fascist Party

War horse

Coppi and many other riders had already been called up for national service, but were allowed time away to compete in the few events which continued through the war.

Bartali who was a devout Christian, continued his long training rides, bordering on daily audaxes around northern Italy. Later he was given a job to do by the Cardinal of Florence, the Archbishop Elia Dalla Costa.

Until 1943, Italy was a safe place for Jewish people until the Nazis began operating in the northern regions and sending them, as well as those who fought against the regime, to concentration camps. Bartali joined the underground Assisi Network run by the Catholic church, which protected those at risk.

On his long training rides he would deliver false identity documents in the handlebars and seatpost of his bike to families across Italy from a secret printing press, enabling them to escape their fate, in turn saving the lives of at least 800 people.

On occasion he was stopped and questioned by the secret fascist police, but since he was high profile - the equivalent of Chris Froome or Bradley Wiggins meandering solo on their bikes around rural areas in the UK - most were hesitant to thoroughly search him and his bike, fearing possible repercussions.

He asked that it not be touched as to disrupt his aerodynamic set-up, thus never revealing the real mission of his long rides.

Not only did Bartali deliver documents, but he harboured his Jewish friend Giacomo Goldenberg and his family in his home with his wife. It was risky business - anyone caught doing such a thing would be killed, as the Oscar-winning film JoJo Rabbit demonstrated.

Bartali inspects graffiti honouring him and other Tour winners

Gino the Pious

"To win the Giro-Tour double is the Holy Grail for stage racers. Very few achieve it and it goes without saying that those who do are freakishly talented," Bradley Wiggins, the 2012 Tour de France winner once wrote, and Bartali - or Gino the Pious as he was nicknamed - fits that mould perfectly.

All of those rides spanning hundreds of miles stood him in good stead for when the war was over and bike racing was back, though he was now much older, perhaps past his peak.

However, Bartali remains the only rider to win two Tours de France 10 years apart - either side of the war. In 1948, he won his second of La Grande Boucle by 26 minutes and 16 seconds.

As the Italian people had long suffered through fascism, a world war and a time of political unrest following the death of Mussolini, their hero was back. Triumphing in France was thought to be the morale boost the country needed, with historians claiming it averted a civil war.

Racing continued, and Coppi, now 10 years older and closer to his peak long after returning from Africa as a British prisoner of war, was gathering as much fame as Bartali with their rivalry. As told to The New York Times in 2009: "In Italy the rivalry of Coppi-Bartali is a religion... your heart is either with one or the other."

"You learn about them at home, at school. They are more famous than almost everyone in Italian history because they gave the country hope."

Their rivalry became so strong, in the same year as Bartali's successful post-war Tour, the pair represented Italy at the World Championships in Holland.

It's reported that both were determined to not let the other win. They fiercely marked one another and despite being two of the greatest cyclists in the world at the time, they did not follow the breakaway group and Briek Schotte of Belgium won. The two did not finish, and were reprimanded by team managers, and various miffed sponsors.

Coppi went on to win a total of five Giro d'Italia and two Tours, but died in January 1960 after contracting malaria. However, in 2002, the BBC reported Italian authorities were looking into claims that Coppi was poisoned. The case remains a mystery.

Bartali's son Andrea visited the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial museum in Jerusalem in 2013, where his father was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations

Humble endings

"You must do good, but you must not talk about it. If you talk about it you're taking advantage of others' misfortunes for your own gain." Late into his life, Bartali finally detailed to his son the feat he had undertaken during the war which had been a secret until then. He even urged Andrea to continue to keep the information under wraps.

Today, to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, Italians sing from balconies in locked-down homes to keep morale up. In the UK we stand on doorsteps applauding our key workers.

Bartali wanted to be remembered for his sporting career on his bike, but when asked about his wartime excursions, he used to say: "I did the only thing I was good at, I cycled."

Sometimes, that's enough.