Chris Froome's Vuelta a Espana bid is a last chance for Ineos Grenadiers

- Published

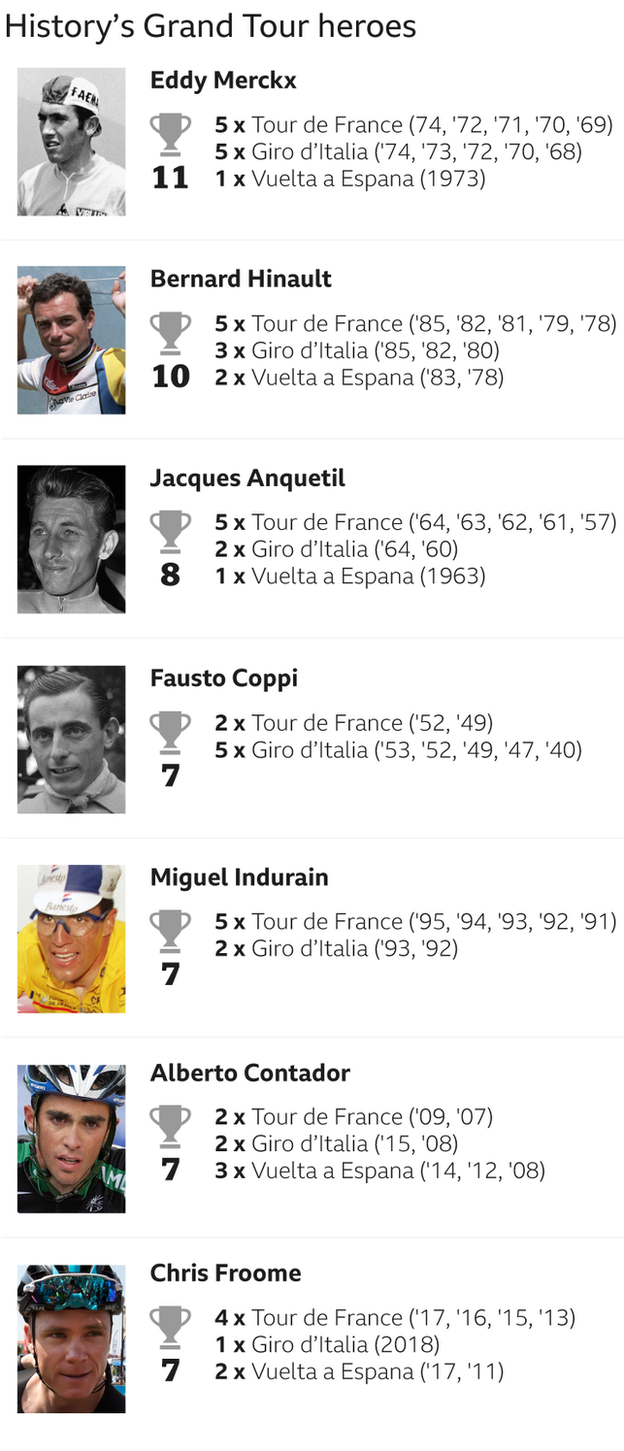

Chris Froome has won the Vuelta twice

It's been a strange year for us all, for very obvious reasons. But if Ineos Grenadiers fail to win a Grand Tour in 2020, you know the world will be in a state of change.

A maelstrom of a season, which began with Chris Froome not having his contract renewed by his near-lifelong paymasters, has the potential to end just as controversially whatever the outcome of the Vuelta a Espana, which begins on Tuesday.

Victory has eluded one of cycling's most decorated riders for more than two and a half years. It's largely due to a horrific crash that ruled him out of the 2019 Tour de France and last year's Vuelta, but it's still the longest he has gone without a win since joining the team in 2009, when they were sponsored by Sky.

So it's a strange world for Froome, who was not picked for the Tour this year and has been deemed surplus to requirements at Ineos at the end of 2020, following a more uncompromising period of negotiation than expected.

Froome, 35, is instead heading for Israel Start-Up Nation - a team largely funded by billionaire businessman Sylvan Adams - to try to win his fifth Tour de France next year.

I've been waiting for this moment - Froome

Back to what you know

But first, one last sortie as an Ineos rider at a race nearly as close to his heart as the Tour de France. A "quietly optimistic" Froome himself admits he has "no great expectations".

But win or lose, it could be controversial.

If he wins: redemption and a message to the team who chose to say goodbye to their most successful product.

Lose, and a fresh start awaits in Israel, as Ineos stare a tier three disaster of a season in the face - failure at all three of road cycling's Grand Tours, at least when it comes to overall victory.

Despite Tao Geoghegan Hart's win on Sunday's 15th stage at the Giro, Ineos acknowledge the season has not gone to plan, to put it mildly. But the atmosphere in the team is defiantly buoyant - driven as it is by the nature of the five stage wins during the ongoing Giro so far, and only after a stray bottle put paid to a general classification bid for Geraint Thomas, who looked like his form had more or less returned.

However, Ineos are only too aware this is an unwanted drought in general classification victories not seen since 2010-11.

Ah yes, those golden autumnal days in Spain was where it all began.

Most will remember Froome's explosion onto the scene during the 2012 Tour de France, when the impatient domestique, as Froome then was, hurried up team-mate Bradley Wiggins to victory.

But it was the 2011 Vuelta in which Froome announced himself to cycling. He was allowed to get the better of Wiggins and eventually beat him to an, at-the-time, second place. That's when Froome's sheer force of will emerged.

In 2019, Froome was handed victory in that Vuelta after Juan Jose Cobo, who finished ahead of him, returned abnormal biological passport results.

Some riders just seem to have an affinity with certain races - it possibly comes with the habit and pattern of conditioning for races at certain times of the year. Froome always seemed to thrive in the warm, golden autumnal glow in Spain - mostly skipping spring's one-day races in the drizzle of northern France and Belgium to focus on the three-week tests.

In the five Vueltas he has completed, Froome has twice been a winner, twice finished second and had one fourth place.

His last Vuelta victory, in 2017, was preceded by his fourth Tour triumph and followed by winning the 2018 Giro as he became only the third man, after legendary pair Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault, to hold cycling's three most prestigious stage races at the same time.

So if there's a place for a Froome renaissance it's at the Grand Tour with the least disrupted start date - it's about six weeks later than usual thanks to the coronavirus pandemic.

Roglic cut a desperate, panicked figure as his Tour win disappeared

Who is he up against?

If any rider's form has been affected the most by Covid-19, it's Froome's. He has been fighting to regain fitness since the near career-ending crash at the 2019 Criterium du Dauphine, in which he sustained multiple serious fractures.

The pandemic-enforced break in racing came just as Froome needed time on the bike. And it showed in the Tour de France warm-up races during August this year, when he was well short of the performances of rival lead riders Geraint Thomas and especially Egan Bernal.

Although try telling to that to 2019 Tour winner Bernal, whose spectacular capitulation during the Tour this year began a trend perhaps never really seen in road cycling's hardest races - when riders simply imploded rather than gradually 'cracked' on the toughest tests.

Bernal's loss of more than seven minutes on stage 15 has largely been forgotten, though, thanks to the even more spectacular burnout of Jumbo-Visma's Primoz Roglic with about 10km of the Tour's nearly 3,000km left - where he lost the race to Tadej Pogacar in a jaw-dropping time-trial finale.

And there lies Froome's next challenge: if he is to beat his own form issues, he then faces a man surely just as furious with himself and sporting fate - Roglic must be determined to make amends by winning the Vuelta after being victorious in it last year.

He doesn't always sound so determined, but Roglic's laconic patter is probably more down to Slovenian to English translation than an aloof approach.

Even if he isn't that bothered about winning Grand Tours, he comes into this race by far the bookies' favourite. Froome a punt-worthy 16/1, below several other contenders, including Jumbo-Visma's other star rider Tom Dumoulin, Thibaut Pinot of Groupama-FDJ and Froome's own team-mate and other protected rider Richard Carapaz.

Will Madrid be ready?

That effect the Covid-led delay on this season may have had on riders' form is hard to measure, as is the risk of holding the race at all. Organisers will be painfully aware that cancellation is a real threat.

The Vuelta - which this year is based almost totally across northern Spain and the Basque region - is effectively run by Tour de France organisers ASO, who delivered that race without any riders contracting coronavirus back in September.

However, with a test and trace protocol almost identical, the ongoing Giro d'Italia lost three riders and two whole teams, who decided to leave amid calls for the race to end.

Once again, the Vuelta begins with the same template - pre-race tests, daily temperature checks and questionnaires. And two rest days where further tests are undertaken for all the riders and team staff.

The only difference this time is that whole teams will only be sent home if more than two riders test positive, instead of additional staff.

Whatever the set-up, it seems very little can stop an asymptomatic case of coronavirus making its way into the team bubbles, and subsequently the whole peloton.

Spain's capital city Madrid is even under a state of emergency imposed after a defiant local government resisted a lockdown.

The emergency measures are set to be over by the time the race reaches its finale in Madrid on 8 November. And if Froome is there, he will at least have got further than any Ineos team leader has managed at a Grand Tour so far this season.

Surely not even Froome truly knows what contribution he can make to this race until he is up and riding - a look at his finishing positions across this season make for uncomfortable reading, even if some were in support of other riders: 37th, 41st, 71st, 91st, DNF.

But few have returned with such ferocity as Froome - who can forget his epic attack from 80km out on stage 19 of the 2018 Giro - and in a year of strange events, who knows what the next three weeks has in store?