Masters 2015: Jordan Spieth - the making of a major champion

- Published

- comments

Spieth's record-breaking Masters win

It began early for Jordan Spieth: when he was three years old and ready for potty-training, his mother Chris decided to bribe him out of nappies by hiding his plastic golf clubs on top of the washing machine until he had done what he had to do.

That bargain could have backfired in a way that was neither good for his golf nor his social standing. Thankfully for the Spieth family, the lure of the clubs was too strong to resist. Eighteen years on, the obsessive kid has become a record-breaking champion.

Ben Crenshaw, another Masters winner schooled in the high winds and heat of Texas, has spoken of looking into the 21-year-old's eyes and seeing the dead-eyed stare of Wild West gunslinger Wyatt Earp.

The final day here at Augusta is often a shoot-out. The pressures of the back nine - greens like glass, fairways steep and narrow, water, water everywhere - have broken older men with far greater experience of these beautiful and brutal yards.

Spieth admitted afterwards that he had struggled to sleep on Saturday night, self-effacingly pointing to his prematurely receding hairline as an indication of the stress he has been under.

Yet even with so many big guns lurking - world number one Rory McIlroy, three-times Masters champion Phil Mickelson, major winner Justin Rose - the callow kid never looked like backing down.

If it seemed less thrilling a finale than we have come to expect from Augusta, it is worth a reminder of the dramatic context: the second youngest winner in Masters history, the first to go to 19 under (before a bogey on the last), more birdies across his four rounds than any player here has ever made, the first man to win it wire to wire in 39 years.

For those who have become desensitised to the scale of his achievement by the very fact that he had led so handsomely throughout, this might help: Rose and Mickelson's score of 14 under for second would have have been the winning tally in all bar five of the previous 78 Masters that have been played.

Spieth has always been aimed at this day. He won the US Junior Amateur title twice (something only Tiger Woods had ever done before), tied for 16th in the Byron Nelson Championship as a 16-year-old (better than Woods ever managed as an amateur in a PGA Tour event) and became the youngest PGA Tour winner in 82 years when he won the John Deere Classic aged 19 years and 11 months.

There is footage of him aged 14 declaring that his ultimate goal in life is to win the Masters. Goals like that are supposed to be good for young sportsmen. They also bring their own burden.

Out on the course, beery breath and cigar smoke swirling in the cool breeze, there were groans and gasps when his overnight lead of four strokes was cut to three at only the second hole and again at the seventh.

So locked in tradition is Augusta that no radios, phones or tablets are allowed through the gates, which preserves a certain atmosphere but also creates its own strange drama.

How was Spieth doing? Was Mickelson closing, was Woods - full of promise of a charge through the front nine - rampaging along as of old?

The only indication, for both players and patrons alike, is first when a volley of noise rolls in through the pine trees from a distant hole and then when the large wooden scoreboards are slowly adjusted by a troupe of men climbing up ladders, like stagehands dressing a particularly elaborate set.

This sort of information vacuum frays the nerves of those watching, let alone a 21-year-old within touching distance of his greatest ambition.

First a hole appears on the board next to the name of the player. Everyone turns and stares. Then, with minimal regard for the anxiety all around, an official will slowly insert a new numbered board.

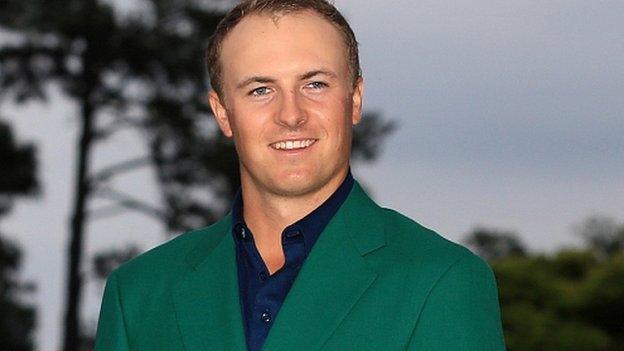

Spieth is the second youngest player to don the Green Jacket at Augusta

That was how Spieth found out that Mickelson was slipping, that McIlroy was improving too slowly, that Woods - name taken off the board entirely - was not the danger of old.

Spieth would not give them a breath of hope.

By the 10th - Rose three-putting the ninth - the lead was back to five. In the pine needles on 11, he bumped and ran beautifully to the right of the green before flicking on a wedge that stopped as if he had it on string.

The crowds here were willing a Mickelson miracle. No-one is loved in these parts in the same way. Mickelson's avuncular grin, relaxed physique and famed generosity (few waitresses leave Phil's table less than $100 better off) have made him some sort of utopian Everyman for the American golf fan.

Spieth's display rendered it instead first a procession and then a coronation.

As he slipped on his first Green Jacket, with all the awkwardness that this sometimes painfully corny ceremony can offer, thoughts wandered off already to where he might go next.

These debut grand triumphs are a lovely stage for a young sportsman, a point in time where everything seems possible, the future unchecked by the vagaries of injury, form or motivation.

Masters 2015: Jordan Spieth receives first Green Jacket

Spieth is still young enough to do exactly what his mother tells him - which is a good thing, when she spots you rather lost for words on the 18th green and tells you to congratulate your playing partner and thank the whooping crowd.

It is a potent reminder of Woods at the same age, winning his debut Masters by exactly the same score and in the same nerveless fashion.

It would take Woods almost two and-a-half years to win his next major. He would reach world number one rather sooner, within two months of his breakthrough at Augusta, and with Spieth already up to second in the rankings that particular piece of history may well repeat.

It was easy to pick out what made the young Woods stand out - his huge driving, a power game that would cause even this living museum of golf to be radically altered.

Even Spieth has trouble describing the best part of his own game, settling on the rather more prosaic "playing badly well" - what others would call course management and precocious self-control.

Crenshaw, poetic in his Masters farewell, spoke of a "jeweller's touch". That does rather better in illustrating how beautifully precise Spieth was in adorning these greens with his short game.

The only man who has putted like this at Augusta is Woods. Different characters in different eras, but in their graduation to the wider world with so much to share.

- Published13 April 2015

- Published13 April 2015

- Published7 April 2015

- Published28 September 2018

- Published12 April 2015

- Published12 April 2015