Six Nations: How England 2017 team match up with 2003 World Cup winners

- Published

- comments

Highlights: England thrash Scotland to retain Six Nations title

Victory against Scotland on Saturday was a world record-equalling 18th in a row for the current England team, who were already on a longer winning streak than Sir Clive Woodward's 2003 world champions - their best was 14.

Extending their run to 19 in Ireland next weekend would secure Eddie Jones' side back-to-back Grand Slams, another feat beyond their legendary predecessors.

However, they will need to win a World Cup of their own to join the 2003 team in the pantheon of English sides.

Next Saturday, the current team do have the chance to do something that eluded Woodward's side in 2001 when, having beaten Scotland by 40 points, they failed in their shot at a Grand Slam as they lost in Dublin.

They are not yet the finished article - and have some way to go to match the achievement of the World Cup winners - but how do they compare man to man to the greats of 2003?

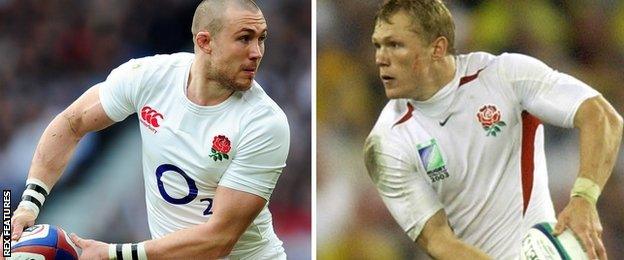

15. Mike Brown v Josh Lewsey

Whereas Josh Lewsey could alternate between the two positions, Mike Brown is definitely a full-back, not a winger.

He is the classic high-ball warrior, relishing the aerial battle that is such a big part of the modern game. Ireland's Rob Kearney, Wales' Dan Biggar and New Zealand's Ben Smith are among the best in the world at fielding the ping-pong kicking exchanges, but none are better than Brown.

Lewsey is a better all-rounder however. He eclipses Brown in attack with his speed, and was rock-solid in defence.

His rib-breaking hit on Australia's Mat Rogers, external the summer before the World Cup final left his opposite number unable to surf as lying on the board was too uncomfortable.

14. Jack Nowell v Jason Robinson

Poor Jack Nowell. Any wing in the world would suffer by this comparison because Jason Robinson had unique attacking skills.

He combined the best step I have ever seen with breathtaking acceleration that would leave defenders choking on dust.

Nowell has boundless energy and always wants to get his hands on the ball and take on the opposition. Still only 23, that attitude has fuelled his improvement with every game.

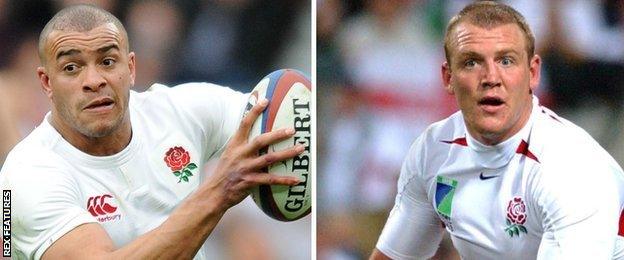

13. Jonathan Joseph v Mike Tindall

What a contrast. Jonathan Joseph and Mike Tindall are two totally different types of players, but each perfectly fitted their eras. Tindall was direct, confrontational and strong, but he also had an eye for the pass and the ability to deliver it.

He was uncompromising in attack and defence, relishing the collision with or without the ball.

Joseph's most eye-catching quality is his pace and ability to pick a defence-piercing line. We saw the perfect demonstration of that in his hat-trick performance against Scotland on Saturday.

His defence is more subtle than Tindall's crash-bang style, but it is equally effective.

12. Owen Farrell v Will Greenwood

While there were differences at outside centre, the two sides' inside centres bring similar assets to the table.

Will Greenwood was both a playmaker and try-scorer for the 2003 side. He was deceptively quick, picking clever lines and gobbling up the yards with his long stride. He has a superb rugby brain, and made time and space for others as well as finding holes to exploit himself.

Farrell has perhaps improved more than any other player under the guidance of England coach Eddie Jones. His running with ball in hand is now a real threat to the defensive line, he knows how to set traps for tacklers and then can deliver a decisive scoring pass. Add to the mix his metronomic goal-kicking and he is becoming world class.

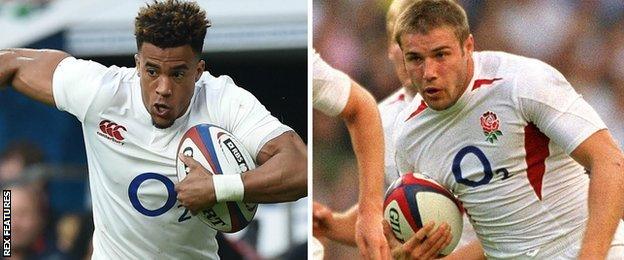

11. Anthony Watson v Ben Cohen

Anthony Watson, with just 23 years and 24 Tests under his belt, is still relatively raw. He has electrifying pace and great feet though and finishes his chances well. Add the greater awareness which should come with experience and he'll be very good.

Cohen had more physicality, but did not sacrifice much speed for it. He had an exceptional step and pace for a big man.

10. George Ford v Jonny Wilkinson

George Ford has a wonderful skill-set - his vision, passing and kicking from hand are generally exceptional. However, he was short of his best in 2016 as the uncertainty over his future at Bath dragged on. Now that his return to Leicester has been sorted, I would like to see the 23-year-old showing his pace with ball in hand and making yards for his team.

What can you say about Jonny Wilkinson? He would deliver just exactly what his coach wanted from him. He understood England's gameplan inside out and executed everything it in his methodical and clever way.

Defensively he set new standards for the position with shuddering hits and, crucially in that World Cup final, he was a penalty-kicking genius.

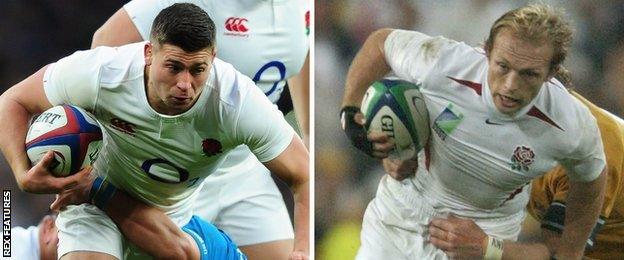

9. Ben Youngs v Matt Dawson

Ben Youngs has sublime matches, good matches and some poor ones. His best - such as the man-of-the-match display in December's 37-21 win over Australia - is world class. He just needs a bit more consistency.

Matt Dawson was another clever player. He had an eye for the gap, a step that would send cameramen the wrong way, and he took on the responsibility in the biggest of matches.

His half-break in the phase before made Jonny Wilkinson's decisive drop-goal that much easier in the World Cup final and his try in the first British and Irish Lions Test in South Africa was typical impudent opportunism.

1. Mako Vunipola v Trevor Woodman

Loose-head Trevor Woodman was probably the unsung hero of the 2003. He was an old-school prop with technical skills that weren't always easily identifiable, but were definitely there.

Mako is a prototype player who is ahead of his time. His ball-carrying ability gives England another option in the loose and his deft handling skills belie his size.

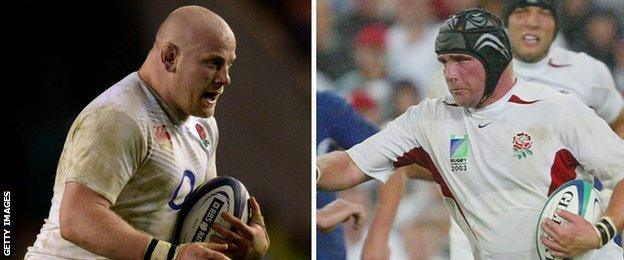

2. Dylan Hartley v Steve Thompson

Steve Thompson was a hooker who bristled with aggression in everything he did. Nothing unusual there perhaps, but he was also one of the best ball-carrying hookers who has played the game, combining pace and a piston-like hand-off.

Hartley leads the current England team by example, whole-hearted and relentlessly competitive. He is more of a set-piece specialist though and it has been noticeable in recent Tests that he has been replaced by the more mobile Jamie George early in the second half as the match opens up.

3. Dan Cole v Phil Vickery

Tight-heads tend to be lone wolves, who live for the scrummage and the chance to cause the opposition front row pain. Phil 'Raging Bull' Vickery though moved out of that comfort zone and carried in the loose to great effect. That was his point of difference.

The current England team are evolving into an all-round footballing side in which one to 15 can run with the ball effectively, but Dan Cole does not fit that model. In addition to his primary role keeping the scrum solid, he is predominantly a breakdown cleaner and is far more effective there than as a runner.

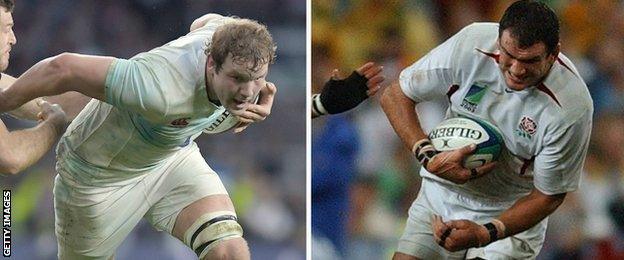

4. Joe Launchbury v Martin Johnson

Martin Johnson was the complete second row, adapting brilliantly throughout his 10-year international career to changing times in rugby. He had a marathon runner's durability, a heavyweight boxer's capacity to fight and a gladiator's instinct for survival. Add in his ferocity in the tight, soaring leaps in the line-out and quiet authority on the pitch and you have one of the best players ever.

Joe Launchbury is a workaholic, getting though his defensive duties, doing the hard yards from first receiver and decorating his performances with slick handling skills.

5. Courtney Lawes v Ben Kay

Ben Kay got the dirty work done for the 2003 England team. He was a clever player on the field, knowing where to put himself for maximum effect. He may have been overshadowed by other bigger names in the public imagination, but he was as important as any of them on the pitch.

Courtney Lawes' muscularity around the pitch means he is unlikely to be similarly overlooked. He has developed his game over the past year. The monster straight-to-showreel hits are still there, but now he has become a more prominent ball carrier as well. That added dimension is something that he needs to keep his shirt in a highly competitive position in the 2017 side.

6. Maro Itoje v Richard Hill

In my opinion, Richard Hill was England's best player for a number of years. He had the pace and intelligence of an open-side flanker and the warrior's instinct of a blind-side flanker. He was truly world class.

It is hard to believe Maro Itoje is only 22 years old. His unique selling point is his rugby intelligence. He makes a veteran's decisions on whether to go into the breakdown, stand out to make a tackle on the fringes or run out wide to plug a gap in the defensive line. He is the prototype modern back-five forward.

7. James Haskell v Neil Back

Two totally different players with different skill-sets and different characters off the field as well, if you judge by their social media skirmish in the wake of the last World Cup., external

Neil Back was the try-scoring tackle jackal at open-side flanker, linking play, covering every blade of grass and rarely making a mistake. He also complemented the rest of the 2003 back row perfectly. Eddie Jones, who indentified England's lack of an out-and-out fetcher like Back as one of their weaknesses before taking charge, is still searching for the perfect balance in that area.

Back was frequently told that he was too small to make it in international rugby before proving his critics wrong. It is never a charge that could be laid against the physically imposing Haskell. Recently he has come up against the best players in the world in his position and held his ground, most noticeably nullifying Australia's Michael Hooper and David Pocock in two Tests in the summer.

8. Billy Vunipola v Lawrence Dallaglio

Just imagine these two running at each other. They are both massive warriors. Lawrence Dallaglio allied raw athleticism from his early days on the sevens circuit to a stubbornly competitive mentality.

He just refused to allow his opposite number to get the better of him. That will ensured he was a world-class player rather than merely an excellent one.

Vunipola seems to brought some of that steely focus to his game after being challenged to establish himself as the best number eight in the world. He has started to dominate games and opposition.

He has a huge amount of natural ability and, at 24, a lot will come down to whether he can continue to climb that steep learning curve he is on.

Jeremy Guscott was talking to BBC Sport's Mike Henson

- Published12 March 2017

- Published13 March 2017

- Published11 March 2017

- Published12 March 2017

- Published11 March 2017

- Published11 March 2017

- Published17 March 2017