Six Nations 2017: George Ford & Owen Farrell - childhood friends to England axis

- Published

- comments

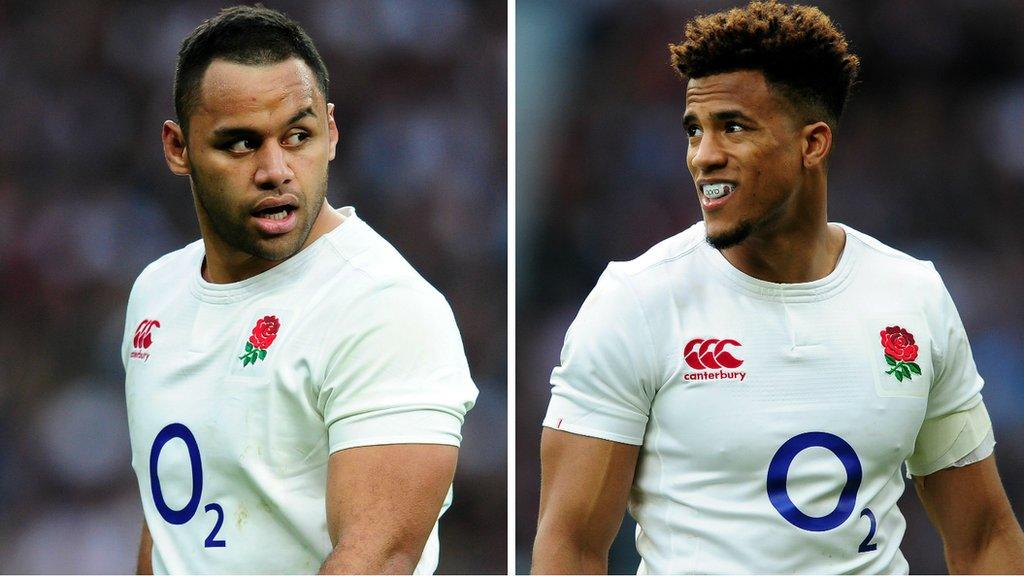

George Ford and Owen Farrell have been playing - and winning - together since they were kids

Six Nations 2017 |

|---|

Venue: Aviva Stadium Date: Saturday, 18 March Kick-off: 17:00 GMT |

Coverage: Listen on BBC Radio 5 live and follow text commentary on the BBC Sport website. |

A buccaneering England team with George Ford at fly-half and his friend Owen Farrell at inside centre. Scotland are the opponents. Early on, Ford sends Farrell into space; a pass later, Jonathan Joseph goes over in the corner.

Near half-time, the two instinctively swap positions, Farrell at first receiver, Ford at second. Off quick ruck ball, Farrell finds Ford, Ford passes round his back to Farrell, the ball goes right, Joseph dives over for his second try.

They say history repeats, not least because no-one listens. Sometimes too it's because very few were watching. This was not last weekend at Twickenham, in front of 84,000 in the stadium and nine million more on television, but a half-empty Kingston Park, Newcastle, in 2009, Ford aged 16, Farrell 17.

Much has changed since the pair were the standout stars in that England Under-18s side. For a long time at senior level they have been rivals in the Premiership and battled for the same number 10 shirt at international level, together but seldom in harmony, contrasting rather than complementary.

Much has stayed the same. This weekend the two - childhood friends, products of the same inadvertent yet remarkable rugby hot-housing, past and present linked by an almost telepathic on-field understanding - will start alongside each other in white once again, the essential pivot in a side with all sorts of history in its sights.

Eight years on from their Kingston Park efforts, can the pair guide England to a second Grand Slam in a row on Saturday?

"Rugby is about connections," says John Fletcher, the first coach to pick the two together, when he took a 15-year-old Ford on tour to Argentina with his England Under-18 side in the summer of 2008, who let the pair room together as they moved up the age groups over the next three years.

"What the two of them had from a very young age, because of their relationship, their experience and their upbringing, was a very strong connection.

"You could tell they liked each other. They are fond both of each other's abilities and each other's personalities. They are very similar in lots of ways - both very driven, very determined, quite obsessive with their practice and preparation, and they spent so much time together they built an awareness of what the other one was going to do before he did it.

"Rugby is a sport where you see pictures, and you have to make decisions based on the pictures you see. What those two have always had is they often see the same picture.

"Both were ridiculously skilful for their age. Their run, kick, pass, their awareness, their decision-making, were really strong. And if you were to stop them at any time in a game or training session and ask them to vocalise what they're seeing and why they're doing it, they would be very similar."

Ford and Farrell were first introduced to each other's abilities while playing rugby league as under-11s, Farrell at the famous Wigan St Pat's club, Ford from 30 miles east in Saddleworth. But they were already linked, both born into league royalty, raised with ball in hand and obsession the all-around norm.

Former England defence coach and Great Britain rugby league player Mike Ford is George Ford's dad

Ford, the son of Mike, scrum-half for Wigan, Oldham and Castleford; elder brother Joe, a Premiership 10 himself; younger brother Jacob to scrap with and wrestle; his next-door neighbour Paul Sculthorpe, St Helens and Great Britain great, always happy to throw a ball around with the kid on the street outside.

Farrell, his dad Andy making his full Wigan debut at 16, winning the Challenge Cup at 17, playing for England at 18, becoming the youngest Great Britain skipper in history at 21; his uncle Wigan captain Sean O'Loughlin; his grandfather Keiron O'Loughlin, who played 260 times for Wigan and 119 times for Widnes, including at stand-off in the Challenge Cup final win over Wigan at Wembley in 1984.

"There were always rugby balls in the house," Farrell tells BBC Sport. "Pretty much everyone in my family used to play. My dad taught me how to kick.

"That's what you want to do as a kid - kick a ball. If there were two of you, you'd go to a field and kick it as far as you can, and the more you have the ball in your hands, messing around, the more you pick up. Just to have a ball in your hand, throwing it around, playing touch rugby with your mates."

When Mike became Saracens head coach in 2005 and made Andy his first major signing, the two families moved into adjacent houses on the same street in Harpenden. And then the burgeoning talents began to coalesce, pushing each other without realising, finding a bond in where they came from and where they wanted to go.

A legend as a rugby league player, Andy Farrell has also been part of the England coaching set-up

"It would be, 'we're not going in for tea until we do 20 perfect passes'," remembers Mike Ford, now head coach at French club Toulon.

"If you get to 19 and the 20th one isn't quite right, you start again. 'We're going to put 30 kicks together.' They've got to be perfect, or we start again. They could be out there a long time, but it mattered.

"They're just rugby nuts. They just wanted to play rugby. They both grew up in an environment that was rugby dominated, and they were very much alike.

"Rugby balls in the house when they were two, three and four, always being thrown about. Going to watch their dads play. Going to watch them train. Training themselves. Even talking over dinner, it was all about rugby.

"That was where they learned. Without thinking it, they were preparing to be where they are today. And it was all fun."

The young Farrell had sat in a Wigan dressing-room containing talents like Jason Robinson, Kris Radlinski and Denis Betts. Ford, 18 months younger but never deferring to his older and bigger friend, had followed his father through his peripatetic coaching career: living in camp with Ireland aged eight; going on the 2005 British and Irish Lions tour as an 11-year-old; sitting in England's dressing-room before the 2007 World Cup final., external

George Ford has known the likes of Jonny Wilkinson - England's all-time lead points scorer - since he was a kid

Hanging round the old Lansdowne Road when his dad was defence coach for Ireland, Ford would field the kicks of fly-halves Ronan O'Gara and David Humphreys. With England, he would cadge free tuition from Jonny Wilkinson. With Farrell, he would do all he could to ensure they had maximum time to put those lessons into practice.

"George was a bit more organised than me," admits Farrell. "He'd do his homework a week in advance, whereas I'd leave it to the last minute. So if I had a bit of homework for the next day, I'd do one and he'd do the other, so we could get out to play."

English Grand Slams have always been built on the essential understanding between fly-half and inside centre: Wilkinson and Will Greenwood, Rob Andrew and Will Carling. Never before have they had the ability to switch roles so naturally and to such attacking effect.

After a spell when international 12s were supposed to be bulldozers and bashers, after four years when England's previous coaching regime tried and failed to find a second point to the attack, when Ford and Farrell were seen as an either/or rather than alliance, Eddie Jones' decision to reunite his northern axis has set his backline free.

Only twice in his 17 matches in charge has he not started Ford and Farrell together - the first time, against Wales last summer, when Farrell was unavailable because of club commitments. In the other, the first Test against Australia in Brisbane a fortnight later, it took him only 29 minutes to haul off Luther Burrell, push Farrell out to 12 and bring Ford off the bench.

It is an old partnership bringing a new look to England, two street footballers bringing a different accent to both dressing-room and style of play.

Wilkinson and Greenwood were public schoolboys, Andrew a Cambridge Blue, Carling an army man (and, like Greenwood, a product of the rugby nursery Sedburgh School, and Hatfield College at Durham University).

Andrew and Carling were integral parts of the last England team to win back-to-back Grand Slams in 1991 and 1992

Farrell and Ford are the league influence on English rugby union come full circle: born when league's brightest talents were being poached by union, raised when coaches were going the same way, maturing with the best of both codes in their feet and fingertips.

"If you grow up in rugby league you're making 20 tackles a game," says Mike Ford. "You're running with the ball 15 times.

"It's massive that they both played league. You look at their core skills. The try England scored at the end against Wales - it looks simple, but those passes George and Owen put together say it all."

Carling, the epitome of the old school, is relishing what the new breed can bring.

"It allows England to play in a variety of ways," he told BBC Sport.

"They are both footballers. They have both got great distribution, as we saw from Elliot Daly's try in the dying minutes against Wales. Both of them can kick, so you can do the tactical kicking game, or you can play with width, because both of them have great awareness of space.

"Rob [Andrew] was more of a Jonny Wilkinson-type, with other sorts of strengths, not least in terms of defence, whereas my role was basically to try to make tries for Jerry Guscott. Even Martin Johnson's team - they relied on Greenwood as that pivot to give them extra width if they wanted it.

"George plays that little bit flatter, which sometimes allows you to attack that little bit more freely than we might have done with Rob. Playing and defending against this England becomes pretty hard."

Mike Ford watched that England Under-18 match in 2009 alongside Wilkinson and the World Cup winner's father. Two years later he would watch his son in the Junior World Cup final, Farrell outside him, the two combining as intuitively as ever in the move that led to England's final try.

They came off second best that afternoon, alongside Joe Launchbury, Mako Vunipola, Daly and Joseph, to a New Zealand side featuring Beauden Barrett, Charles Piutau and Brodie Retallick.

Highlights: England thrash Scotland to retain Six Nations title

Against Ireland on Saturday, successive Grand Slams and a world record of 19 consecutive Test victories in their sights, second will only be seen as failure.

"I watched George and Owen play in every age group, and what they were doing at first and second receiver, we're only just seeing it at this level," says Ford Sr.

"Like against Scotland, how the ball comes off the top of the line-out and Owen's at first receiver and finds George and Joseph scores his first try, or how for Watson's try they swapped it round.

"They're both the same. They see each other driving to be the best they can every day, and being together it rubs off on them both. They both train that little bit harder. Get two, three, four players in your team who do that, and you've got a pretty special team - and that's what England have at the moment.

"They have their best rugby ahead of them. What Eddie [Jones] has done brilliantly is challenging them. Asking them to get better all the time.

"And they love that. You go back to the 20 passes. 'Lads, come in for your tea. Have you done your 20 perfect passes?'"

- Published16 March 2017

- Published16 March 2017

- Published16 March 2017

- Published17 March 2017