Concussion in rugby: Brain expert calls for limit to contact training

- Published

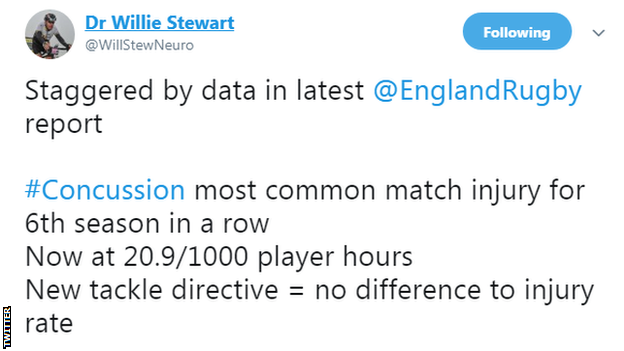

The concussion rate in elite English rugby has risen for six straight years

Rugby should limit - or ban entirely - contact training sessions during the season to reduce the risk of brain injury, a leading concussion expert has said.

Consultant neuropathologist Dr Willie Stewart believes the rates of concussion in the professional game are "unacceptably high" and the sport must change to keep its players safe.

English rugby's latest annual injury audit showed concussion was the most reported injury for the sixth successive season in 2016-17, while more than one-third of all injuries were sustained during training.

The rate of concussion rose for the seventh year running, reaching a level of 20.9 concussions per 1,000 hours of match play.

Although there are inconsistencies in data collection between sports, that figure is higher than similar reported rates in boxing and means that, for every elite English rugby match, one player is expected to suffer a brain injury.

A March report found 20.9 concussions were sustained per 1,000 hours of match play in English professional rugby - roughly one per game

The report also found World Rugby's heightened tackle sanctions for contact to the head had no effect on the frequency of concussion.

English rugby chiefs will now work with the global governing body to implement an eight-point plan designed to make the game safer.

Meanwhile, the concussion rate continues to rise, year on year, and nothing rugby's powerbrokers have done to date has proved an effective method of slowing it down.

"I know some former professional players who looked forward to the weekend match because it gave them a rest," Stewart told BBC Scotland. "During the week they were just getting destroyed.

"We're talking about diagnosable, recognisable brain injuries - there's more and more evidence coming that it's not just the ones that produce symptoms that are the problem, it's the cumulative effect of all the smaller ones as well, the ones that don't necessarily produce symptoms.

Fraser Brown saw a specialist this year after sustaining multiple brain injuries

"If, during the week, instead of having several days of contact training with more and more impacts on top of each other, you do away with that, you're going to phenomenally reduce the number of impacts over the season and that can't be a bad thing.

"There's a whole lot of unnecessary exposure. Professional rugby players don't forget by Monday or Tuesday how to play rugby, how to tackle, how to go into a ruck."

'The injury risk is far too high'

Fatigue was widely blamed for England's poor Six Nations campaign, with 12 of the squad that finished fifth having toured with the British and Irish Lions last summer, in addition to their club demands.

Players in Scotland and Ireland are centrally-contracted, with restrictions placed on the workload of internationalists.

"What was suggested for England's performances during the Six Nations? They'd played too much rugby," Stewart said.

Maro Itoje was one of 16 English players to tour with the 2017 British and Irish Lions

"Why were Ireland, Scotland successful? Perhaps better player management. The internationalists were protected.

"You get the best from the players over the season, but their careers should last longer as well. You can see players like Stuart Hogg lasting the course rather than having to pack it in early because they're struggling.

"If you want to see the best players playing the best game for as long as possible then it's sensible game management and sensible training management.

"That's easy and, if World Rugby were serious about it, they would say, 'This is a mandate from on-high, under World Rugby's code, professional players must not do contact training during the season any more than one day a week, for example, or not at all'.

Stuart Hogg helped Scotland to three wins from five Six Nations matches this year

"World Rugby is responsible for the game. If leagues choose to ignore that, they are then culpable for what happens 10-20 years down the line. World Rugby can say it did what it could.

"The injury risk is far too high and we know players who are tired and who have got niggly injuries are at risk of further injury.

"So it may be that, by cutting back on contact time during the week, you actually reduce injuries in matches as well."

'Referees have an impossibly hard task'

In response to the English data, World Rugby appeared to lay the blame at the door of referees, suggesting RFU match officials had not policed their directive as stringently as demanded.

Former Scotland prop and qualified physician Dr Geoff Cross says today's referees face a mountainous task in overseeing matches.

"There is a problem we want to be hard on - brain injury," said Cross, who won 40 caps from 2009 to 2015. "Looking for someone to lay the failure of a policy or a plan on is not being hard on the problem - it's being hard on the people.

On his Scotland debut in 2009, Cross knocked himself out in a collision with airborne Wales full-back Lee Byrne

"We need the people onside to be hard on the problem. That's referees, players, officials in the governing bodies, managers.

"We can talk about conditioning, neck strength, tackle technique, law changes and how they are enforced by referees, who have an impossibly hard job, because there's more to watch and catch than you can possibly have the attention and time to do.

"The important thing is to find a way to structure the laws so that the behaviour is as safe as it can be - safe behaviour is rewarded and dangerous behaviour doesn't get a reward, so you stop doing it."

World Rugby statement in response to Dr Stewart's comments: |

|---|

"World Rugby and its unions are committed to an evidence-based approach to injury reduction at all levels of our sport, including the priority area of head injuries. We have implemented a number of education, management and prevention initiatives that are proven to be successful in further protecting players. These include the HIA, Graduated Return to Play and Tournament Player Welfare Standards at the elite level as well as lowering the acceptable height of the tackle, global education and the Activate warm-up programme across all levels of the game. Research highlights the importance of individual player load management in reducing injury risk in training and playing environments and we have previously outlined our view that everyone in the game should pay close consideration to this area." |

'If in doubt, sit them out'

Scotland is the first nation to adopt uniform, cross-sport guidelines on managing brain injuries, which advise rest, then step-by-step rehabilitation.

Cross is a strong advocate of cultural change, urging players to take responsibility for their own wellbeing.

"The recent grassroots key message - if in doubt, sit them out - and an attempt to change the culture from 'if you're tough, you keep going when injured and play through', to: 'if you're not able to play to the best of your ability and there are fit, capable, motivated people behind you, who you are preventing from getting on and contributing by not leaving the field, it's entirely possible you are in fact harming the performance of the team'," he said.

"That's a very important point for professional rugby players to consider. The reason it's particularly important with brain injury is because you're not yourself once you've had a concussion and things you would normally do, how you would take further collisions, how you respond to things around you, aren't the same.

"My suspicion is that's truer for brain injury than it is for musculoskeletal injuries, which rugby players are a lot more comfortable with."

'It's a very big and humble thing to ask'

How realistic, though, is expecting a player in the savage throes of a professional contest to willingly walk off - particularly while reeling from a potentially rationale-wrecking, sense-scrambling collision?

"I've certainly had that feeling: I'll just give it 'til the next play, the next 10 minutes, 'til half-time, then I'll decide," Cross admits.

"I was fortunate in spite of that decision-making.

Cross (with beard) scored the second of his two Scotland tries against Tonga in 2014

"What can we do to encourage people? If someone is looking to play rugby for as long as possible, if you can demonstrate to them that there's behaviour that shortens their career and leaves them with problems afterwards, they would listen to that.

"If you're interested in the team's performance, and there are people able to do a better job than you because they aren't in an injured and vulnerable position, the decision is clear.

"That's a very big and humble thing to ask. It's possible and the game would be better if we could achieve that."

'I'd take the benefits and the memories'

There is an ever-lengthening list of players whose careers have been stalled or halted altogether by the effects of multiple brain injuries.

There are retired rugby men of Cross's vintage who still grapple with the lingering toll of those blows, but many more who emerge from the game neurologically unscathed.

"If I was going into professional rugby now from school, on the balance of risk, I'd still want to do that," Cross said.

Numerous international players have had their careers curtailed by injuries to the head and brain

"I'd take the cardiovascular benefits and the memories.

"The difficult question to ask me is what would it have to look like for me to say, 'Actually, no thanks, it isn't worth it anymore'?

"Right now, I don't have an honest answer. That might be confessing some biases I have.

"The closest I could get to that was if I saw a regression in culture back to: 'just be tough, don't worry about tomorrow because you're living for today'.

"You have one brain for your whole life and most people are intending life to last a long time. It's worth having precautions and being careful with it."

'Rugby needs to change'

Stewart's "gut feeling" is that the benefits Cross describes still outweigh the risks of brain injury, but insists the sport must do more to tackle the problem.

"There comes a point where you have to say this is not an acceptable level and rugby reached that point several years ago," he said. "Rugby needs to change and cannot continue exposing people to a brain injury every match.

Dr Willie Stewart (left) was heavily involved in creating Scotland's cross-sport concussion guidelines

"If we think of boxing being a sport people shy away from because of the risks of brain injury then we're putting rugby in that league - that's why it has to change.

"They're getting better at spotting the injury but that doesn't take away from the fact that the injuries are happening.

"The bottom line is, we think brain injury is a problem and may pose a long-term problem for people who participate in these sports. Wouldn't it be better if we had the benefits and reduced the risks?"