The hidden strengths of unloved concrete

- Published

Nearly 20 years ago, poor families in Coahuila state in Mexico were offered an unusual handout from a social programme called Piso Firme. It was not a place at school, a vaccination, food, or even money. It was $150 (£118) worth of ready-mixed concrete.

Workers would drive concrete mixers through poor neighbourhoods, stop outside a home, and pour the porridge-like mixture through the door, right into the living room.

They showed the occupants how to spread and smooth the gloop, and made sure they knew how long to leave it to dry. Then they drove off to the next house.

Piso Firme means "firm floor", and when economists studied the programme, external, they found that the ready-mixed concrete dramatically improved children's education.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Previously, the floors were made of dirt, which let parasitic worms thrive, spreading diseases that stunted kids' growth and made them miss school.

Concrete floors are much easier to keep clean. So the kids were healthier, and their test scores improved. Economists also found that parents in the programme's households became happier, less stressed and less prone to depression.

That seems to be $150 well spent.

Beyond the poor neighbourhoods of Coahuila state, concrete often has a less wonderful reputation.

Soulless structures

It has become a byword for ecological carelessness: concrete is made of sand, water and cement, and cement takes a lot of energy to produce. The production process also releases carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.

That might not be such a problem in itself - after all, steel production needs a lot more energy - except that the world consumes absolutely vast quantities of concrete: five tonnes, per person, per year. As a result, the cement industry emits as much greenhouse gas as aviation.

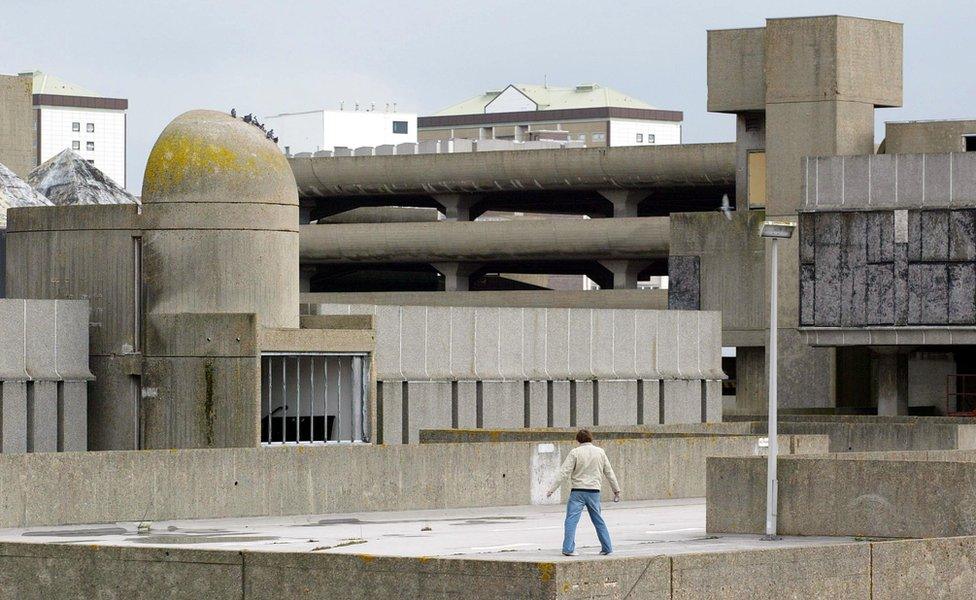

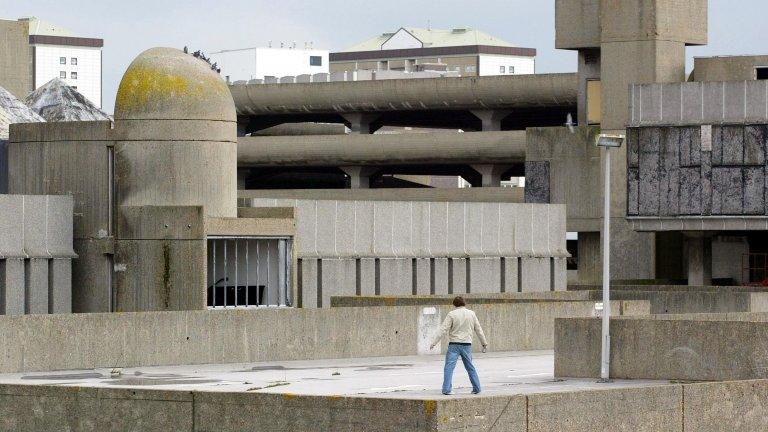

Architecturally, concrete implies lazy, soulless structures: ugly office blocks for provincial bureaucrats, multi-storey car parks with stairwells that smell of urine.

Portsmouth's Tricorn Centre was regularly described as the UK's ugliest building, before its demolition

Yet it can also be shaped into forms that many people find beautiful - think of the Sydney Opera House or Oscar Niemeyer's Brasilia cathedral.

Perhaps it is no surprise that concrete can evoke such confusing emotions.

The very nature of the stuff feels hard to pin down. "Is it stone? Yes and no," opined the great American architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1927. "Is it plaster? Yes and no. Is it brick or tile? Yes and no. Is it cast iron? Yes and no."

However, the fact that it is a great building material has been recognised for millennia - perhaps even since the dawn of human civilization.

There is a theory that the very first settlements, the first time that humans gathered together outside their kinship groups - nearly 12,000 years ago at Gobekli Tepe in southern Turkey - was because someone had figured out how to make cement, and therefore concrete.

Oscar Niemeyer's Brasilia Cathedral was constructed from 16 concrete columns, each weighing 90 tonnes

It was certainly being used over 8,000 years ago by desert traders to make secret underground cisterns, some of which still exist in modern day Jordan and Syria. The Mycenaeans used it over 3,000 years ago to make tombs you can see in the Peloponnese in Greece.

Shockingly modern

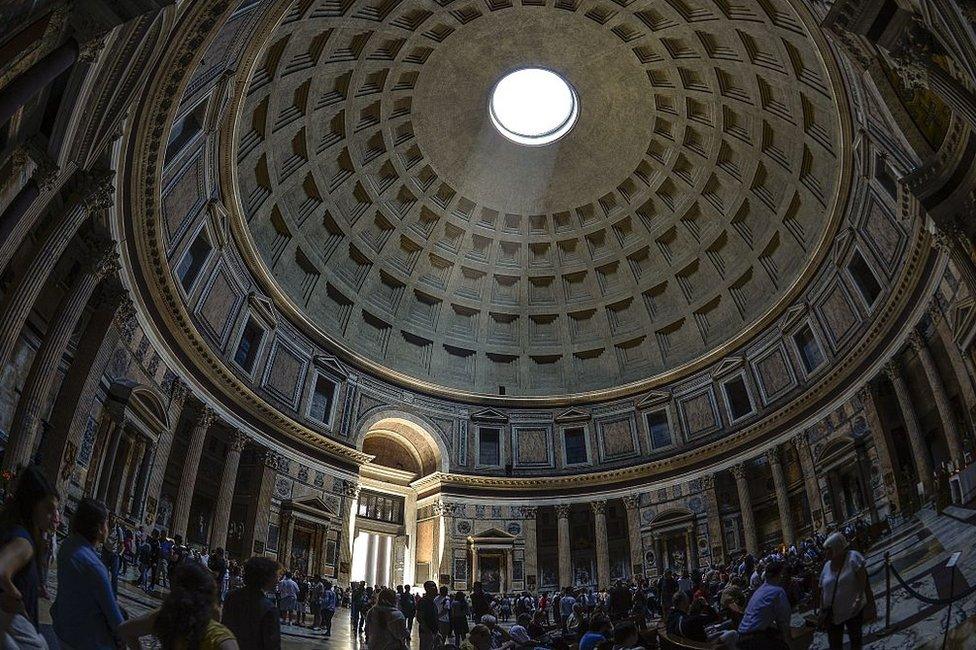

The Romans were also serious about the stuff.

Using a naturally occurring cement from volcanic ash deposits at Puteoli, near Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius, they built their aqueducts and their bathhouses with concrete.

Walk into the Pantheon in Rome, a building that will soon celebrate its 1,900th birthday. Gaze up at what was the largest dome on the planet for centuries, arguably until 1881.

You're looking at concrete. It is shockingly modern.

Many Roman brick buildings are long gone - but not because the bricks themselves have decayed. They've been taken apart, cannibalised for parts. Roman bricks can be used to make modern buildings.

But the concrete Pantheon? One of the reasons it has survived for so long is because the solid concrete structure is absolutely useless for any other purpose.

Bricks can be reused, concrete cannot. It can only be reduced to rubble. And the chances of it becoming rubble depend on how well it is made.

Bad concrete - too much sand, too little cement - is a death-trap in an earthquake. But well-made concrete is waterproof, storm proof, fireproof, strong and cheap.

More from Tim Harford

That is the fundamental contradiction of concrete: incredibly flexible during construction, utterly inflexible afterwards.

In the hands of an architect or a structural engineer, concrete is a remarkable material. You can pour it into a mould, set it to be slim and stiff and strong in almost any shape you like. It can be dyed, or grey, it can be rough or polished smooth like marble.

But the moment the building is finished, the flexibility ends: cured concrete is a stubborn, unyielding material.

'Fatal' flaw

Perhaps that is why the material has become so associated with arrogant architects and autocratic clients - people who believe that their visions are eternal, rather than likely to need deconstructing and reconstructing as circumstances change.

In a million years, when our steel has rusted and our wood has rotted, concrete will remain.

But many of the concrete structures we're building today will be useless within decades. That's because, over a century ago, there was a revolutionary improvement in concrete - but it's an improvement with a fatal flaw.

In 1867, a French gardener, Joseph Monier, was unhappy with the available range of flower pots, and devised concrete pots, reinforced with a steel mesh.

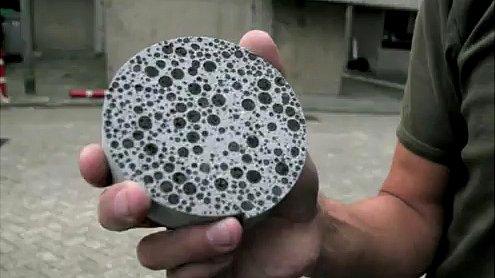

Well-made reinforced concrete is much stronger and more practical

Less than 20 years later, the elegant idea of pre-stressing the steel was patented. This allowed engineers to use much less of it, and less concrete too.

Reinforced concrete is much stronger and more practical than the unreinforced stuff. It can span larger gaps, allowing concrete to soar in the form of bridges and skyscrapers.

But if cheaply made, it can rot from the inside as water gradually seeps in through tiny cracks, and rusts the steel.

This process is currently destroying infrastructure across the United States. In 20 or 30 years' time, China will be next.

China poured more concrete in the three years after 2008 than the United States poured during the entire 20th Century, and nobody thinks that it was all made to exacting standards.

Environmental rewards

There are many schemes to make concrete last longer, including special treatments to prevent water getting through to the steel.

There is "self-healing" concrete, full of bacteria that secrete limestone, which re-seals any cracks. And "self-cleaning" concrete, infused with titanium dioxide, breaks down smog, keeping the concrete sparkling white.

The concrete sails of Rome's Dives in Misecordia church include titanium dioxide

Improved versions of the technology may even give us street surfaces that can clean up cars' exhaust fumes.

Researchers are trying to make concrete with less energy use and fewer carbon emissions. The environmental rewards for success will be high.

Yet ultimately, there are many more things we could be doing with the simple, trusted technology we already have.

Hundreds of millions of people around the world live in dirt-floor houses. Their lives could be improved with a programme like Piso Firme. Other studies have shown large gains from laying concrete roads in rural Bangladesh - improving school attendance, agricultural productivity and boosting farm workers' wages.

Perhaps concrete serves us best when we use it simply.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published5 May 2016

- Published4 May 2016

- Published17 August 2015

- Published2 August 2014

- Published4 March 2014

- Published30 October 2012

- Published12 November 2011