Battery bonanza: From frogs' legs to mobiles and electric cars

- Published

Murderers in early 19th-Century London sometimes tried to kill themselves before they were hanged.

Failing that, they asked friends to give their legs a good, hard pull as they dangled from the gallows to ensure their death. Their freshly hanged bodies, they knew, would be handed to scientists for anatomical studies.

They didn't want to survive the hanging and regain consciousness while being dissected.

If George Foster, executed in 1803, had woken up on the lab table, it would have been in particularly undignified circumstances.

In front of an enthralled and slightly horrified London crowd, an Italian scientist with a flair for showmanship placed an electrode into Foster's rectum.

Some onlookers thought Foster was waking up. The electrically charged probe caused his body to flinch and his fist to clench. Applied to his face, electrodes made his mouth grimace and an eye twitch open.

The scientist had modestly assured his audience that he wasn't actually intending to bring Foster back to life, but added, "Who knows what might happen?"

The police were on hand, in case Foster needed hanging again.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Foster's body was being galvanised - a word coined for Luigi Galvani, the Italian scientist's uncle.

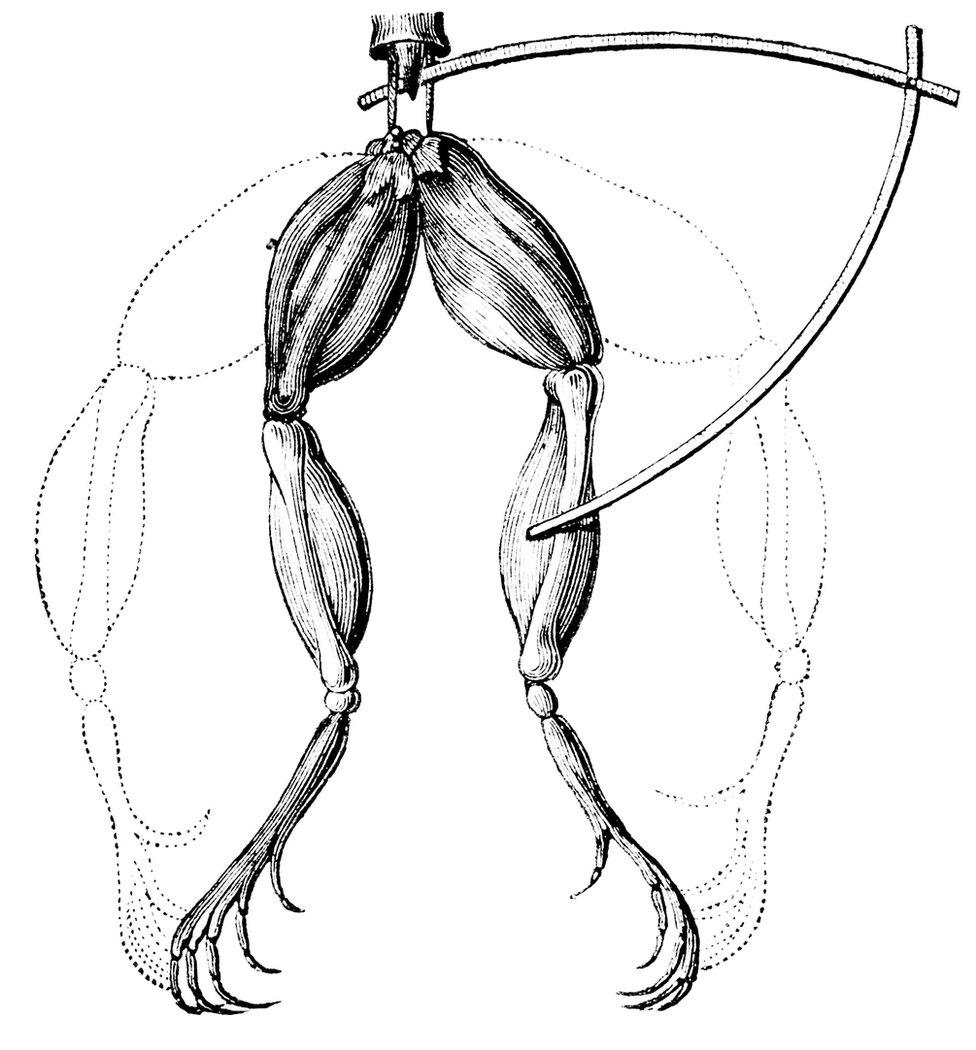

In 1780s Italy, Galvani had discovered that touching the severed legs of a dead frog with two different types of metal caused the legs to jerk.

Wrong in a useful way

Galvani thought he had discovered "animal electricity", and his nephew was carrying on the investigations.

Galvanism briefly fascinated the public, inspiring Mary Shelley's novel, Frankenstein.

Galvani discovered frogs' legs would twitch when touched by electrodes

Galvani was wrong. There is no animal electricity.

You can't bring hanged bodies back to life, and Victor Frankenstein's monster remains safely in the realms of fiction.

But Galvani was wrong in a useful way, because he showed his experiments to his friend Alessandro Volta, who had better intuition about what was going on.

The important thing, Volta realised, wasn't that the frog flesh was of animal origin.

It was that it contained fluids which conducted electricity, allowing a charge to pass between the different types of metal.

When the two metals connected - Galvani's scalpel touching the brass hook on which the legs were hung - the circuit was complete, and a chemical reaction caused electrons to flow.

Volta experimented with different combinations of metal and different substitutes for frogs' legs. In 1800, he showed that you could generate a constant, steady current by piling up sheets of zinc, copper and brine-soaked cardboard.

Alessandro Volta described his findings in a letter to the President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, in March 1800

Volta had invented the battery, and gave us a new word - volt. His insight won him admirers. Napoleon made him a count.

The lithium breakthrough

But it wasn't especially practical, not at first.

The metals corroded, the salt water spilled, the current was short-lived, and it couldn't be recharged.

It was 1859 before we got the first rechargeable battery, made from lead, lead dioxide and sulphuric acid. It was bulky, heavy, and acid sloshed out if you tipped it over. But it was useful - the same basic design still starts our cars.

The first "dry" cells - the familiar modern battery - came in 1886. The next big breakthrough took another century.

In 1985, Akira Yoshino patented the lithium-ion battery, later commercialised by Sony.

Lithium was popular with researchers as it's very light and highly reactive: lithium-ion batteries can pack lots of power into a small space.

Lithium-ion batteries power many popular devices.

Unfortunately, lithium also has an alarming tendency to explode when exposed to air and water, so it took some clever chemistry to make it acceptably stable.

Without the lithium-ion battery, mobiles would likely have been much slower to catch on.

Consider what cutting-edge battery technology looked like in 1985.

Motorola had just launched the world's first mobile phone, the DynaTAC 8000x. Known affectionately as "the brick", it weighed nearly 1kg. Its talk time was 30 minutes.

More from Tim Harford

The technology behind lithium-ion batteries has certainly improved: 1990s laptops were clunky and discharged rapidly. Today's sleek ultraportables will last for a long-haul flight.

Still, battery life has improved at a much slower rate than other laptop components, such as memory and processing power.

Where's the battery that's light and cheap, recharges in seconds, and never deteriorates with repeated use? We're still waiting.

But there is no shortage of researchers looking for the next breakthrough.

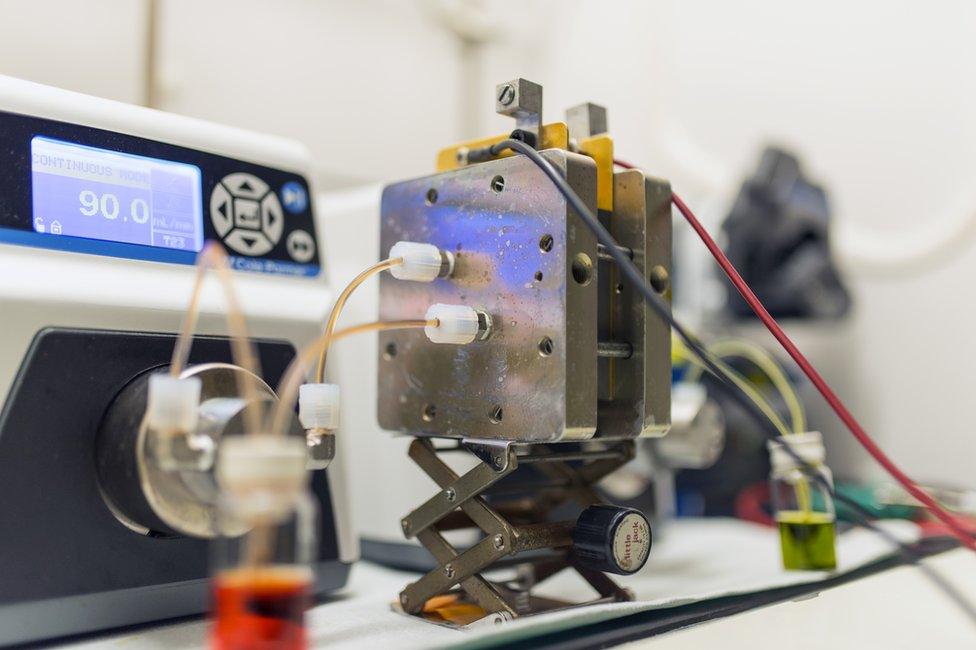

Some are developing "flow" batteries, which work by pumping charged liquid electrolytes.

Harvard researchers working on "flow" batteries have identified a new class of organic molecules, inspired by vitamin B2, that can safely store electricity

Some are experimenting with new materials to combine with lithium, including sulphur and air. Some are using nanotechnology in the wires of electrodes to make batteries last longer.

But history counsels caution: game changers haven't come along often.

Can batteries boost the grid?

In the coming decades, the truly revolutionary development in batteries may not be in the technology itself, but in its uses.

We think of batteries as things that allow us to disconnect from the grid. We may soon see them as the thing that makes the grid work better.

Gradually, the cost of renewable energy is coming down. But even cheap renewables pose a problem - they don't generate power all the time.

You'll always have a glut of solar power on summer days and none on winter evenings. When the sun isn't shining and the wind isn't blowing, you need coal or gas or nuclear to keep the lights on, so why not run them all the time?

Solar panels cannot deliver power all the time - even in sunny spots

A recent study of south-eastern Arizona's grid weighed the costs of power cuts against the costs of CO2 emissions, and concluded that solar should provide just 20% of power. And Arizona is pretty sunny.

Grids need better ways of storing energy to better exploit renewable power.

One time-honoured solution is pumping water uphill when you have spare energy, and then - when you need more - letting it flow back down through a hydropower plant. But that requires conveniently contoured terrain.

Could batteries be the solution?

Perhaps. It depends partly on the extent to which regulators nudge the industry in that direction, and on how quickly battery costs come down.

Elon Musk hopes they'll come down very quickly indeed.

The entrepreneur behind electric car maker Tesla is building a gigantic lithium-ion battery factory in Nevada. Musk claims it will be the second-largest building in the world, after the one where Boeing manufactures its 747s.

Quick-charging car batteries are essential for electric cars

Tesla is betting that it can significantly wrestle down the costs of lithium-ion production, not through technological breakthroughs, but through sheer economies of scale.

Tesla needs the batteries for its vehicles, of course. But it's also among the companies already offering battery packs to homes, businesses and power grids.

If you have solar panels on your roof, a battery in your house gives you the option of storing your surplus day-time energy for night-time use, rather than selling it back to the grid.

We're still a long way from a world in which electricity grids and transport networks can operate entirely on renewables and batteries.

But in the race to limit climate change, the world needs something to galvanise it into action.

The biggest impact of Alessandro Volta's invention may be only just beginning.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published3 April 2017

- Published16 January 2017

- Published9 December 2016

- Published21 November 2016

- Published2 September 2016