Do passports restrict economic growth?

- Published

"What would we English say if we could not go from London to the Crystal Palace or from Manchester to Stockport without a passport or police officer at our heels? Depend upon it, we are not half enough grateful to God for our national privileges."

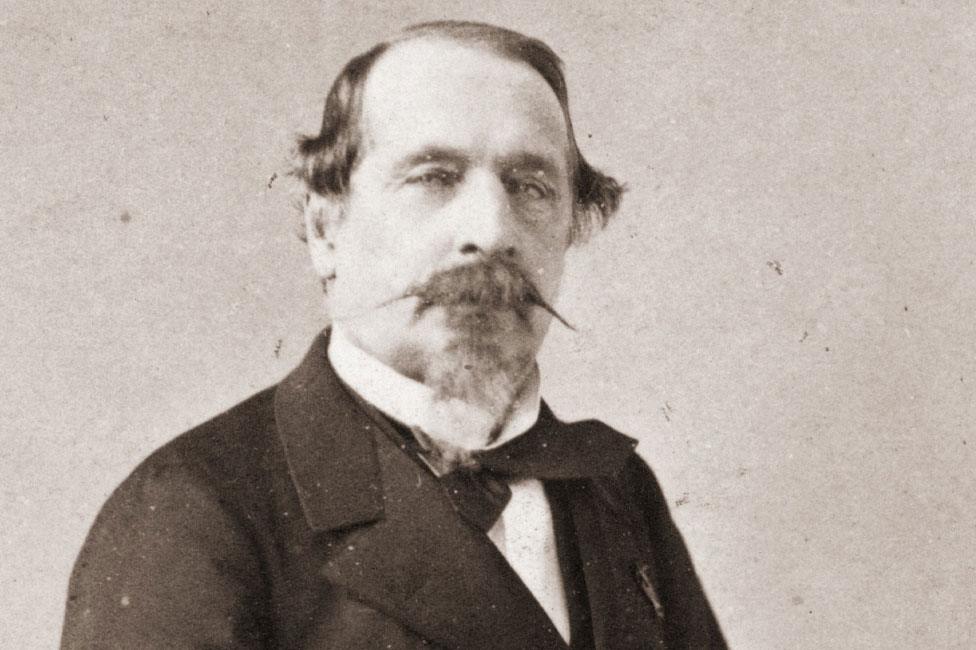

So wrote an English publisher named John Gadsby, travelling through Europe in the mid-19th Century.

This was before the modern passport system, wearily familiar to anyone who has ever crossed a national border.

You stand in a queue, you proffer your standardised booklet to a uniformed official, who glances at your face to check that it resembles the image of your younger, slimmer self.

Perhaps she quizzes you about your journey, while her computer checks your name against a terrorist watch-list.

For most of history, passports were neither so ubiquitous nor so routine.

They were, essentially, a threat: a letter from some powerful person requesting the traveller pass unmolested - or else.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

The concept of passport as protection goes back to biblical times. And protection was a privilege, not a right.

Gentlemen such as Gadsby who wanted a passport needed a personal link to the relevant government minister.

As Gadsby discovered, the more zealously bureaucratic continental nations had realised the passport's potential as a tool of social and economic control.

A century earlier, French citizens had to show paperwork not only to leave the country, but to travel from town to town.

'Oppressive invention'

While wealthy countries today secure their borders to keep unskilled workers out, municipal authorities historically used them to stop skilled workers from leaving.

As the 19th Century progressed, railways and steamboats made travel faster and cheaper. As Martin Lloyd details in his book The Passport, restrictive travel documents were unpopular.

France's Napoleon III abolished passports in 1860

France's Emperor Napoleon III shared Gadsby's admiration for the more relaxed British approach. He described passports as "an oppressive invention", and abolished them in 1860.

France was not alone. More and more countries either formally abandoned passport requirements or stopped enforcing them, at least in peacetime.

You could visit 1890s America without a passport, though it helped if you were white.

The visitors greeted by the newly installed Statue of Liberty in the 1890s did not need passports

Some South American countries enshrined passport-free travel in their constitutions. In China and Japan, foreigners needed passports only to venture inland.

By the turn of the 20th Century, only a handful of countries still insisted on passports to enter or leave. It seemed possible they might soon disappear altogether.

Migrant crisis

What would today's world look like if they had?

One morning in September 2015, Abdullah Kurdi, his wife and two young sons boarded a dinghy in Bodrum, Turkey, hoping to make it 4km (2.5 miles) across the Aegean Sea to the Greek island of Kos.

But the dinghy capsized in rough seas. Abdullah managed to cling to the boat, but his wife and children drowned.

When the body of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish beach and was photographed by a Turkish agency journalist, the image became an icon of the migrant crisis that had convulsed Europe all summer.

Tens of thousands of migrant families have tried to cross from Turkey to Greece

The Kurdis hadn't planned to stay in Greece. They hoped eventually to start a new life in Vancouver, where Abdullah's sister Teema is a hairdresser.

There are easier ways to travel from Turkey to Canada than taking a dinghy to Kos.

Abdullah had money: the 4,000 euros (£2,500; $4,460) he paid a people-smuggler could have bought plane tickets for them all - if they had had the right passports.

Since the Syrian government denied citizenship to ethnic Kurds, the family had no passports. But even with Syrian documents, they couldn't have boarded a plane to Canada. Passports issued by Sweden or Slovakia, or Singapore or Samoa would have been fine.

It can seem natural that the name of the country on our passport determines where we can travel and work - legally, at least.

Discrimination?

But it's a relatively recent historical development, and, from a certain angle, it's odd.

Many countries ban employers from discriminating among workers based on characteristics we can't change: whether we're male or female, young or old, gay or straight, black or white.

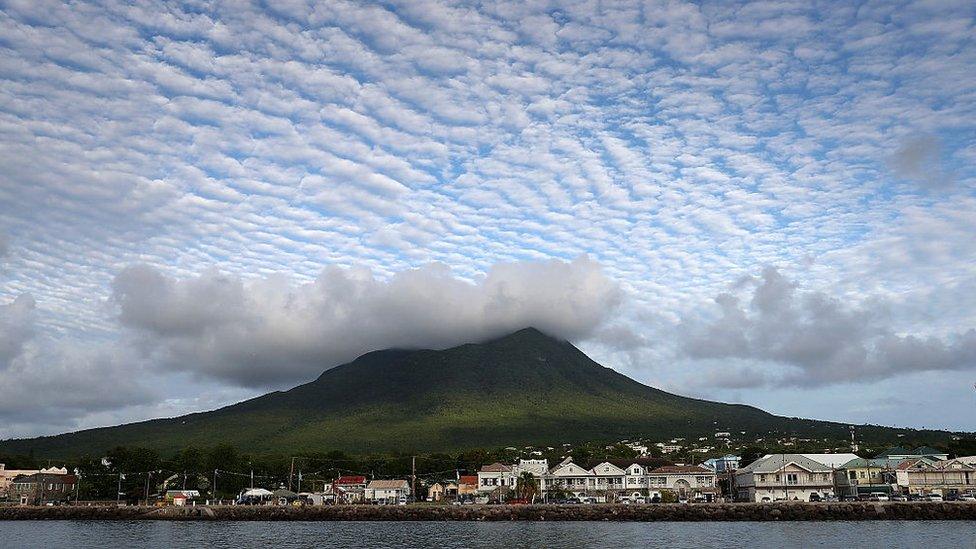

It's not entirely true that we can't change our passport: $250,000 (£193,000) will buy you one from St Kitts and Nevis, external.

St Kitts established its "Citizenship by Investment" programme in 1984

But, mostly, our passport depends on the identity of our parents and location of our birth. And nobody chooses those.

Despite this, there's no public clamour to judge people not by the colour of their passport but by the content of their character.

Less than three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, migrant controls are back in fashion.

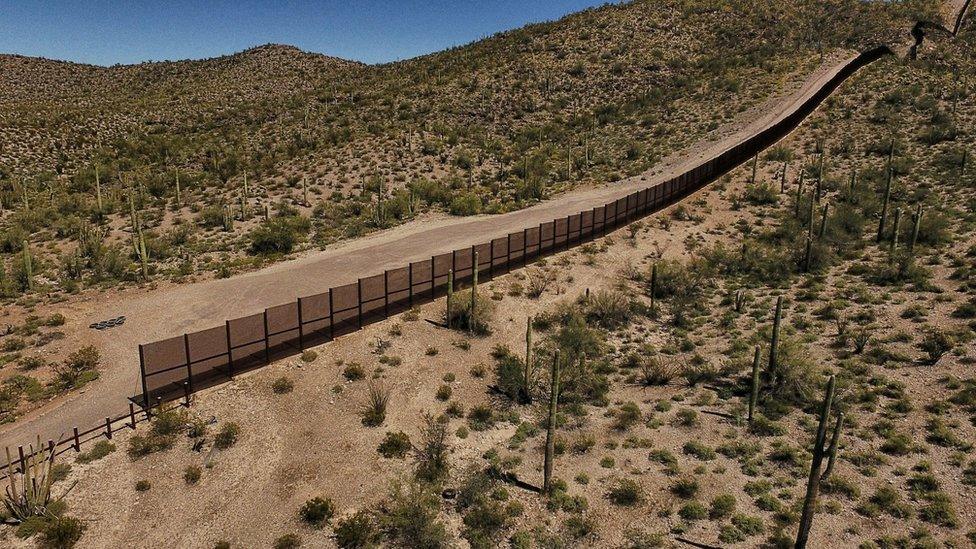

Donald Trump calls for a wall along the US-Mexico border.

US President Trump insists that Mexico will reimburse the US for the cost of the border wall, estimates of which vary wildly

The Schengen zone cracks under the pressure of the migrant crisis.

Europe's leaders scramble to distinguish refugees from "economic migrants", the assumption being that someone who isn't fleeing persecution - but merely wants a better job or life - should not be let in.

Politically, the logic of restrictions on migration may be increasingly hard to dispute.

Winners and losers

Yet economic logic points in the opposite direction. In theory, whenever you allow factors of production to follow demand, output rises.

In practice, all migration creates winners and losers, but research indicates there are many more winners. In the wealthiest countries - by one estimate - five in six of the existing population are made better off by the arrival of immigrants.

So why doesn't this translate into popular support for open borders?

More from Tim Harford

There are practical and cultural reasons why migration can be badly managed: if public services aren't upgraded quickly enough to cope with new arrivals, or belief systems prove hard to reconcile.

The losses also tend to be more visible than the gains.

Suppose a group of Mexicans arrive in America, ready to pick fruit for lower wages than Americans are earning. The benefits - slightly cheaper fruit for everyone - are too widely spread and small to notice, while the costs - some Americans lose their jobs - produce vocal unhappiness.

It should be possible to arrange taxes and public spending to compensate the losers. But it doesn't tend to work that way.

The economic logic of migration often seems more compelling when it doesn't involve crossing national borders.

Security concerns

In 1980s Britain, with recession affecting some of the country's regions more than others, Employment Minister Norman Tebbit notoriously suggested - or was widely interpreted as suggesting - that the jobless should "get on their bikes" to look for work.

Some economists calculate global economic output would double if anyone could get on their bikes to work anywhere.

That suggests today's world would be much richer if passports had died out in the early 20th Century. There's one simple reason they didn't: World War One intervened.

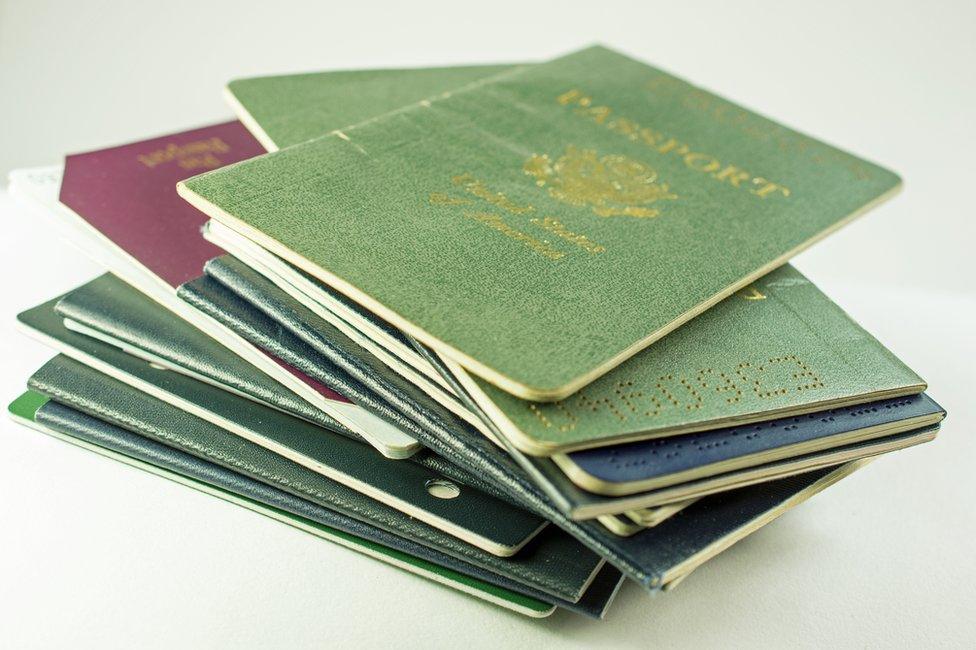

Modern passports are remarkably uniform in format

With security concerns trumping ease of travel, governments imposed strict new controls on movement, and they proved unwilling to relinquish those powers once peace returned.

In 1920, the newly formed League of Nations called an "International Conference on Passports, Customs Formalities and Through Tickets", which effectively invented the passport as we know it.

From 1921, the conference said, passports should be 15.5cm (6in) by 10.5cm, 32 pages, bound in cardboard, with a photo. The format has changed remarkably little since.

Like John Gadsby, anyone with the right colour passport can only count their blessings.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published31 March 2017

- Published15 April 2017

- Published5 April 2017

- Published15 January 2017

- Published4 June 2014