How the plough made the modern economy possible

- Published

Imagine catastrophe. The end of civilisation. This complex, intricate modern world of ours is finished.

Don't worry about why. Maybe it was swine flu or nuclear war, killer robots or the zombie apocalypse.

And now imagine that you are one of the lucky few survivors. You have no phone - who would you phone anyway? No internet. No electricity. No fuel.

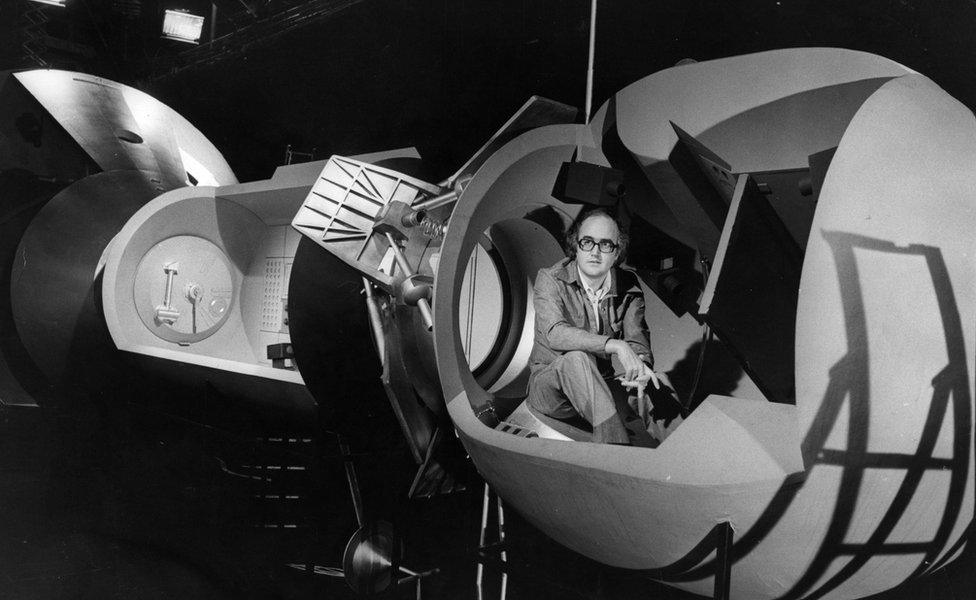

Four decades ago, the science historian James Burke posed that scenario in his TV series Connections, and asked a simple question.

James Burke asked which technology would be most useful in a post-apocalyptic world

Surrounded by the wreckage of modernity, without access to the lifeblood of modern technology, where do you start again? What do you need to keep yourself - and the embers of civilisation - alive?

And his answer was a simple yet transformative piece of technology: a plough.

And that's appropriate, because it was the plough that kick-started civilisation in the first place, and which - ultimately - made our modern economy possible.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world in which we live.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Around 12,000 years ago, humans were almost entirely nomadic, hunting and foraging their way into every niche they could find all across the world.

But the world was emerging from a cold snap: things started to get hotter and dryer.

People who had been hunting and foraging in the uplands found that the plants and the animals around them were dying. Animals migrated to the river valleys in search of water, and people followed.

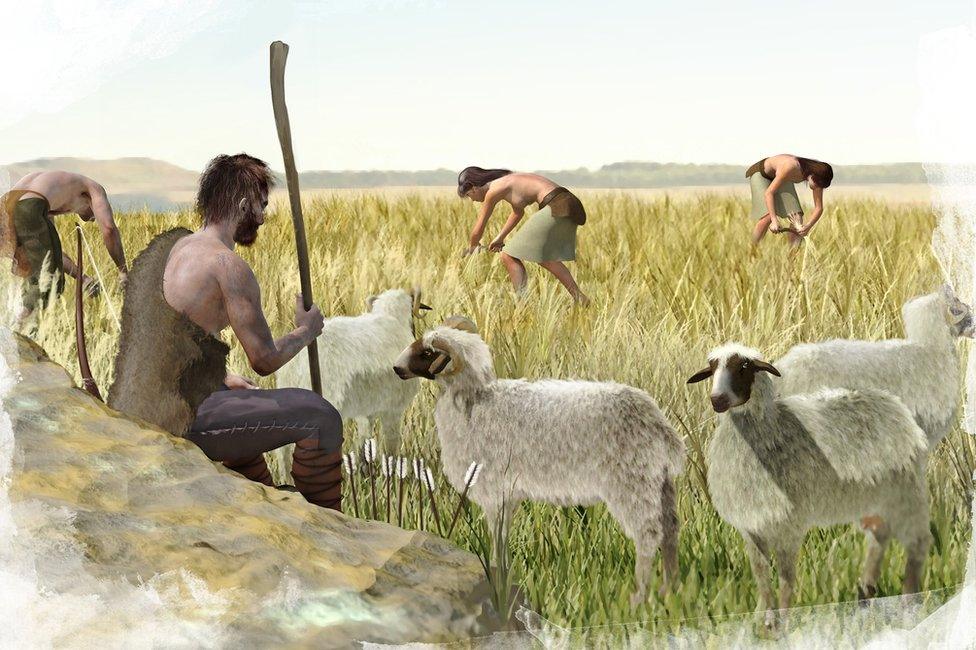

The roots of agriculture

This shift happened in many places: over 11,000 years ago in Western Eurasia, nearly 10,000 years ago in India and China, and more than 8,000 years ago in Mesoamerica and the Andes.

Eventually it happened almost everywhere.

Confined to these fertile but geographically-limited river valleys, people had to settle down and farm - which meant breaking up the surface of the soil, bringing nutrients to the surface and letting moisture seep deeper, out of sight of the harsh sun.

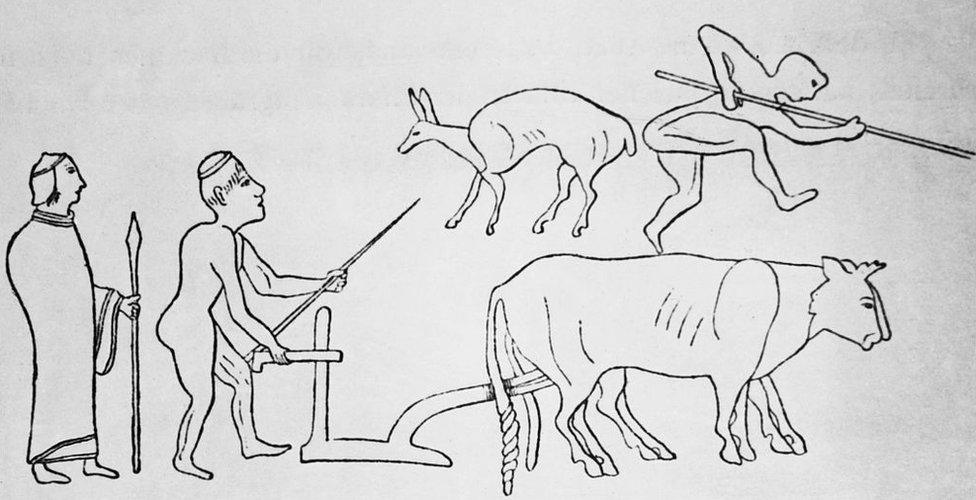

Ancient Greek farmers using a scratch plough, drawn by a pair of oxen, circa 400 BC

At first they used sharp sticks, held in the hand, but soon they switched to a simple scratching plough, pulled by a pair of cows. It worked remarkably well.

Agriculture began in earnest.

It was no longer just a desperate alternative to the dying nomadic lifestyle, but a source of real prosperity. When farming was well-established - 2,000 years ago in Imperial Rome, 900 years ago in Song dynasty China - these farmers were five or six times more productive than the foragers they had replaced.

Think about that: it becomes possible for a fifth of the population to grow enough food to feed everyone.

What do the other four-fifths do? Well, they're freed up to specialise in other things: firing bricks, felling trees, building houses, mining ore, smelting metals, constructing roads, making cities and building civilisation.

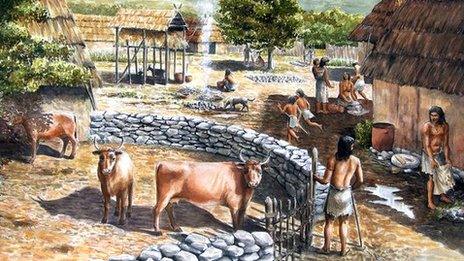

Inequality paradox

But there's a paradox: more plentiful supplies of food mean more competition for control of the surplus.

That competition creates rulers and ruled, masters and servants, and inequality of wealth unheard of in hunter-gatherer societies.

It enables the rise of kings and soldiers, bureaucrats and priests - to organise wisely, or live idly off the work of others.

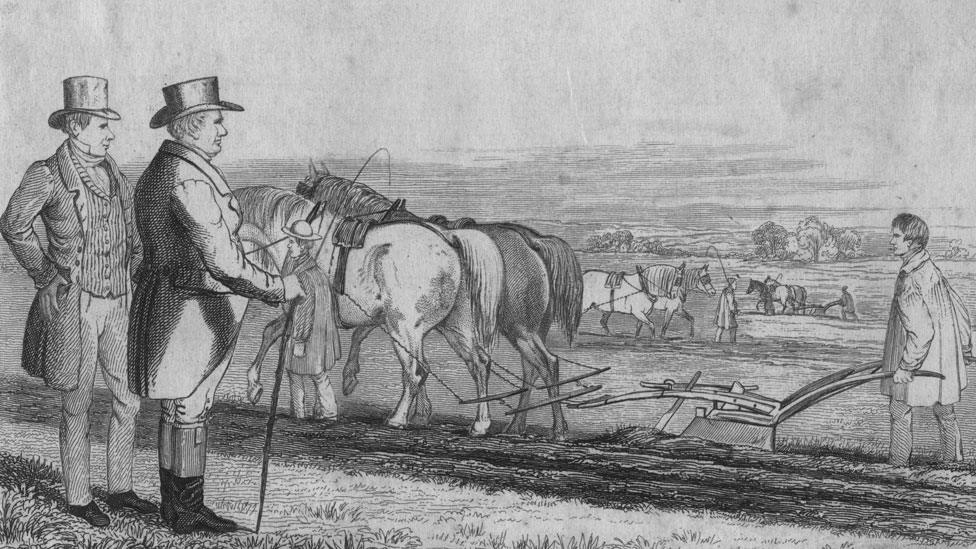

Social hierarchies developed, with agricultural labourers overseen by higher ranking individuals

Early farming societies could be astonishingly unequal.

The Roman Empire, for example, seems to have been close to the biological limits of inequality. If the rich had had any more of the Empire's resources, most people would simply have starved.

But the plough did more than create the underpinning of civilisation - with all its benefits and inequities. Different types of plough led to different types of civilisation.

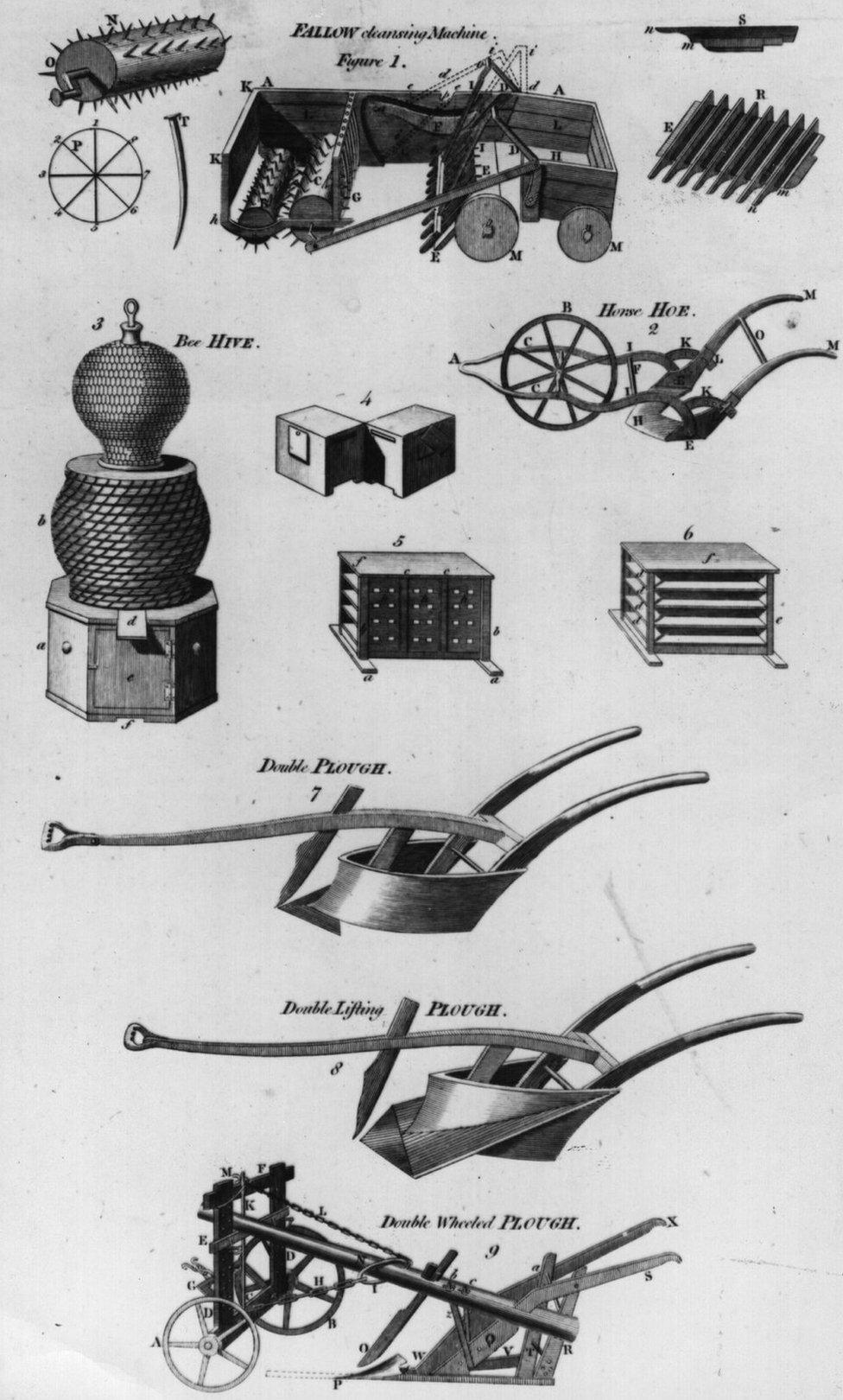

The first simple scratch ploughs used in the Middle East worked very well for thousands of years, and spread to the Mediterranean, where they were ideal tools for cultivating the dry, gravelly soils.

But then a very different tool - the mouldboard plough - was developed, first in China more than 2,000 years ago, and much later in Europe.

The mouldboard plough cuts a long thick ribbon of soil, and turns it upside down. In a dry soil, that's a counterproductive exercise as it squanders precious moisture.

But in the fertile wet clays of Northern Europe, the mouldboard plough was vastly superior, improving drainage and killing deep-rooted weeds, turning them into mere compost.

The dry-soil scratch plough needed only two animals to pull it, and worked best with criss-cross ploughing in simple, square fields. All this made farming an individualistic practice: a farmer could live alone with his plough, oxen and land.

Farming as community practice

But the wet-clay mouldboard plough required a team of eight oxen - or better, horses - and who had that sort of wealth? It was most efficient in long thin strips often a step or two away from someone else's long thin strips.

As a result, farming became more of a community practice: people had to share the plough and its animals, and resolve disagreements. They gathered together in villages. The mouldboard plough helped usher in the manorial system in Northern Europe.

The plough also reshaped family life. The equipment was heavy, so ploughing became seen as men's work. But wheat and rice needed more preparation than nuts and berries, so women increasingly found themselves at home preparing food.

The development of farming helped reshape gender roles

There's a study of Syrian skeletons from 9,000 years ago which finds evidence that women were developing arthritis in their knees and feet, apparently from kneeling, twisting and grinding grain.

And since women no longer had to carry toddlers around while foraging, they had more frequent pregnancies.

Agrarian societies may even have changed sexual politics.

If you have land, you can hand it down to your children. And if you're a man, that means you might become increasingly concerned about whether they really are your children - after, all, your wife is spending all her time at home. Is she really doing nothing but grinding grain?

So one theory - speculative but intriguing - is that the plough intensified men's policing of women's sexual activity. If true, that's never really gone away.

More from Tim Harford:

All of this raises the question of whether inventing the plough was entirely a good idea.

Not that it didn't work - it worked brilliantly - but along with all the benefits of civilisation, it seems to have enabled the rise of misogyny and tyranny.

Archaeological evidence also suggests that the early farmers had far worse health than their immediate hunter-gatherer forebears. With their diets of rice and grain, they were starved of vitamins, and stunted.

'Worst mistake'?

As societies switched to agriculture, the average height of both men and women shrank by around 6 inches (15cm), and there's ample evidence of the rise of parasites, disease and childhood malnutrition.

Archaeological evidence suggests early farmers were less healthy than hunter-gatherers

Jared Diamond, author of Guns, Germs and Steel, calls the adoption of agriculture "the worst mistake in the history of the human race", external.

You may wonder why, then, agriculture spread so quickly.

But we've already seen the answer: the food surplus enabled larger populations, and let societies afford soldiers.

Armies of even stunted soldiers will have been sufficiently powerful to drive the remaining hunter-gatherer tribes off all but the most marginal land.

Even there, the few remaining modern nomadic tribes still have a relatively healthy diet, with a rich variety of nuts, berries and animals.

One Kalahari bushman was asked why his tribe hadn't copied their neighbours and picked up the plough.

"Why should we," he replied, "when there are so many mongongo nuts in the world?"

So there you are, one of the few survivors of the end of civilisation.

Would you re-invent the plough, and start the whole thing over again? Or would you be content with the mongongo nuts?

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published11 November 2015

- Published16 July 2013

- Published7 April 2011

- Published10 November 2010