How Chinese mulberry bark paved the way for paper money

- Published

Almost 750 years ago, a young Venetian merchant named Marco Polo wrote a remarkable book chronicling his travels in China.

The Book of the Marvels of the World was full of strange foreign customs that Marco claimed to have seen.

But there was one that was so extraordinary, Marco Polo could barely contain himself: "Tell it how I might," he wrote, "you never would be satisfied that I was keeping within truth and reason."

What had excited Marco so much? He was one of the first Europeans to witness an invention that remains at the foundation of the modern economy: paper money.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world in which we live.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Of course, the paper itself isn't the point. Modern paper money isn't made of paper - it's made of cotton fibres or plastic.

And the Chinese money that so fascinated Marco Polo wasn't quite paper either.

It was made from a black sheet derived from the bark of mulberry trees, signed by multiple officials and, with a seal smothered in bright red vermilion, authenticated by the Chinese emperor Kublai Khan himself.

Kublai Khan announced that officially stamped mulberry bark was money - and lo, it was

The chapter of Marco Polo's book was titled, somewhat breathlessly: "How the great Khan Causes the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All over His Country".

The point is, that whatever these notes were made of, their value didn't come from the preciousness of the substance, as with a gold or silver coin.

Instead, the value was created purely by the authority of the government.

'Genius' system

Paper money is sometimes called fiat money - the Latin word "fiat" means "let it be done". The Great Khan announces that officially stamped mulberry bark is money - and lo, let it be done. Money it is.

The genius of this system amazed Marco Polo, who explained that the paper money circulated as though it were gold or silver itself. Where was all the gold that wasn't circulating? Well, the emperor kept a tight hold of that.

The Mulberry money itself wasn't new when Marco Polo heard about it. It had emerged nearly three centuries earlier, around the year 1000 in Sichuan, China.

Sichuan was a frontier province, bordered by foreign and sometimes hostile states. China's rulers didn't want valuable gold and silver currency to leak into foreign lands, and so they imposed a bizarre rule. Sichuan had to use coins made of iron.

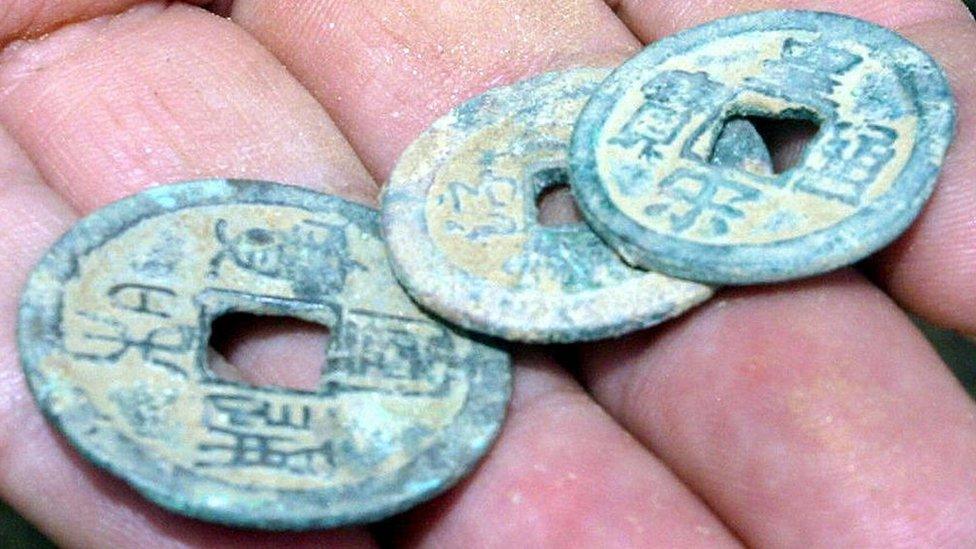

These Chinese coins dating back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279) were found in 2005

Iron coins aren't terribly practical. If you traded in a handful of silver coins - 50g worth - you'd be given your own body weight in iron coins.

Even something simple like salt was worth more, gram for gram, than iron - so if you went to the market for groceries, your sackful of coins on the way there would weigh more than the bag of goods that you brought back.

Sichuan merchants had a problem, as William Goetzmann explains in his book Money Changes Everything. It was illegal to use gold and silver coins, and impractical to use iron coins. It's no surprise that they began to experiment with an alternative.

That alternative was called "jiaozi", or "exchange bills". Instead of carrying around a wagonload of iron coins, a well-known and trusted merchant would write an IOU, and promise to pay his bill later when it was more convenient for everyone.

That was a simple enough idea. But then there was a twist, a kind of economic magic. These "jiaozi", or IOUs, started to trade freely.

More from Tim Harford:

Suppose I supply some goods to the eminently reputable Mr Zhang, and he gives me an IOU. When I go to your shop later, rather than paying you with iron coins - who does that? - I could write you an IOU.

Primitive paper money

But it might be simpler - and indeed you might prefer it - if instead I give you Mr Zhang's IOU. After all, we both know he's good for the money.

Now you, and I, and Mr Zhang, have together created a kind of primitive paper money - it's a promise to repay that has a marketable value of its own - and can be passed around from person to person without being redeemed.

This is very good news for Mr Zhang, because as long as people keep finding it convenient simply to pass on his IOU as a way of paying for things, Mr Zhang never actually has to stump up the iron coins.

Effectively, he enjoys an interest-free loan for as long as his IOU continues to circulate. Better still, it's a loan that he may never be asked to repay.

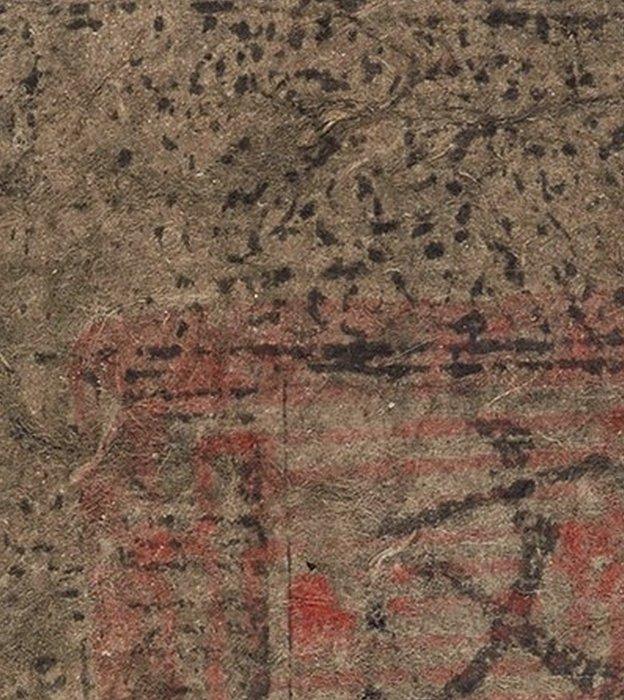

A fragment of one of the earliest surviving banknotes, which was printed in the early 1260s

No wonder the Chinese authorities started to think these benefits ought to accrue to them, rather than to the likes of Mr Zhang.

At first they regulated the issuance of jiaozi, but then outlawed private jiaozi and took over the whole business themselves.

Modern step

The official jiaozi currency was a huge hit, circulating across regions and even internationally. In fact, the jiaozi even traded at a premium, because they were so much easier to carry around than metal coins.

Initially, the government-issued jiaozi could be redeemed for coins on demand, exactly as the private jiaozi had been. This was logical: it treated the paper notes as a placeholder for something of real value.

But the government soon moved stealthily to a fiat system, maintaining the principle but abandoning the practice of redeeming jiaozi for metal. Bring an old jiaozi in to the government treasury to be redeemed, and you would receive a crisp new jiaozi.

That was a very modern step. The money we use today all over the world is created by central banks and it's backed by nothing in particular except the promises to replace old notes with fresh ones.

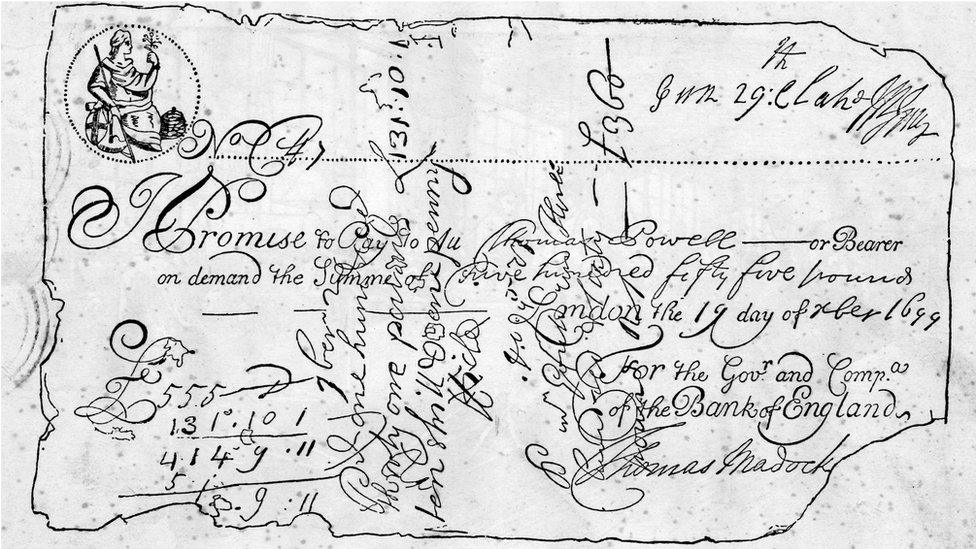

The oldest known British bank note, issued by the Bank of England in 1699

We've moved from a situation where Mr Zhang's IOU circulates without ever being redeemed, to the mind-bending situation where the government's IOUs circulate despite never being redeemed.

Temptation

For governments, fiat money represents a temptation: a government with bills to pay can simply print more money. And when more money chases the same amount of goods and services, prices tend to go up.

The temptation quickly proved too great to resist.

The Song dynasty issued too many jiaozi. Counterfeiting was also a problem. Within a few decades of its invention in the early 11th century, jiaozi was devalued and discredited, trading at just 10% of its face value.

Other countries have since suffered much worse. Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe are famous examples of economies collapsing into chaos as excessive money-printing rendered prices meaningless.

Zimbabwe has seen extraordinarily high inflation

The abysmal world record for hyperinflation is held by Hungary in 1946, where prices trebled during the course of every day. Walk into a Budapest cafe back then, and it was better to pay for your coffee when you arrived, not when you left.

The gold standard

These rare but terrifying episodes have convinced some economic radicals that fiat money can never be stable.

They yearn for a return to the days of the gold standard, when paper money could always be redeemed for a little piece of the precious metal held inside Fort Knox.

Gold has been used as currency for thousands of years

But mainstream economists generally now believe that pegging the money supply to gold is a terrible idea. Most regard low and predictable inflation as no problem at all - perhaps even a useful lubricant to economic activity.

And while we may not always be able to trust central bankers to print just the right amount of new money, it probably makes more sense than trusting miners to dig up just the right amount of new gold.

The ability to fire up the printing presses is especially useful in crisis situations.

After the 2007 financial crisis, the US Federal Reserve pumped trillions of dollars into the economy, without creating inflation. In fact, the printing presses were metaphorical: those trillions were simply created by key-strokes on computers in the global banking system.

As a wide-eyed Marco Polo might have put it: "The great Central Bank Causes the Digits on a Computer Screen, Made into Something Like Spreadsheets, to Pass for Money".

Technology has changed, but what passes for money continues to astonish.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published13 March 2017

- Published12 August 2016

- Published22 April 2016

- Published25 April 2014

- Published2 July 2012

- Published26 March 2012