Curiosity rover made near-perfect landing

- Published

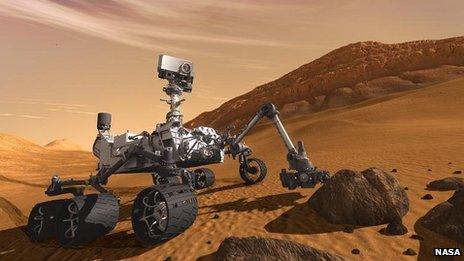

The rover put down on a flat spot inside a crater. The cliffs of the crater wall can be seen in the distance

Nasa engineers say they are thrilled at just how well the Curiosity Mars rover landing system worked.

They have now had a few days to examine data transmitted from the vehicle as it made its historic touchdown on Monday (GMT).

The analysis indicates that all events in the entry, descent and landing (EDL) sequence occurred at, or very close to, their predicted times.

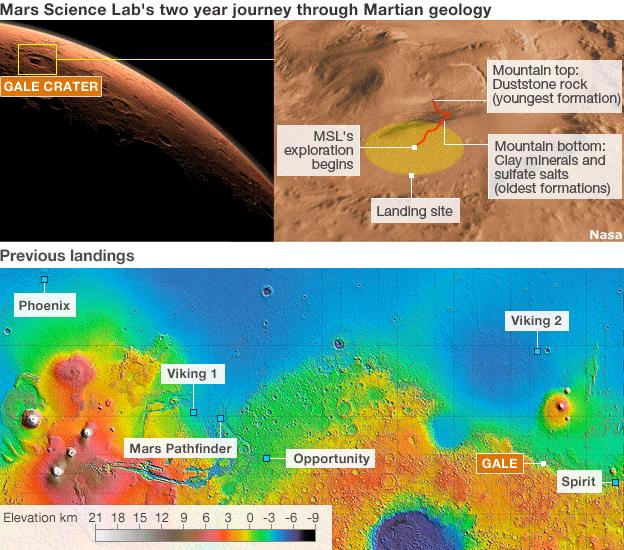

Curiosity, external put down just 2.4km from the targeted point on the planet's surface.

This was on the flat floor of Gale Crater, a deep depression on Mars' equator.

Allen Chen: "We can tell a lot from only 1MB of data"

Most of the data recorded by Curiosity's onboard inertial sensors has yet to be downlinked to Earth, but even the small fraction of information that is in the possession of engineers has allowed them to reconstruct the key moments of the landing sequence.

"Right now we've only got about 1MB of data - that's less than a camera phone picture," explained Allen Chen, the EDL operations lead at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

"That's the data that was sent back via [the satellites] Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Oribter (MRO) on the landing night.

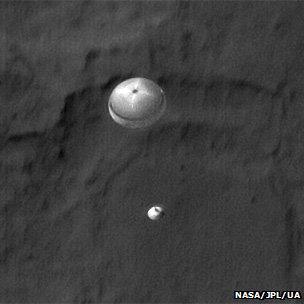

Perfect job: The satellite image of the descent parachute shows it did not rip

"That 1MB of data was intended to help us figure out what happened in case we failed. All the events that we saw during EDL happened within five to 10 seconds of the expectations. This was a very nominal EDL - very few surprises, everything went well," he told BBC News.

The time from touching the top of the atmosphere to touching the surface was seven minutes and 12 seconds - very close to a round "seven minutes of terror", which was the phrase used to describe the difficulties of EDL.

Curiosity's protective capsule entered the top of the atmosphere moving at Mach 24 (24 times the speed of sound), and took 3.5 minutes to slow to Mach 2 and get ready to deploy its parachute.

Most of the energy of entry was dissipated in the form of heat as the front shield pushed up against the Martian air.

"We pulled a little over 11 Earth gs (gravitational force). So if you were a human riding onboard, it would have been a bit of a rough ride. But, fortunately, Curiosity is made of some pretty sturdy stuff and she handled that just fine," said EDL team member Gavin Mendock from Nasa's Johnson Space Center.

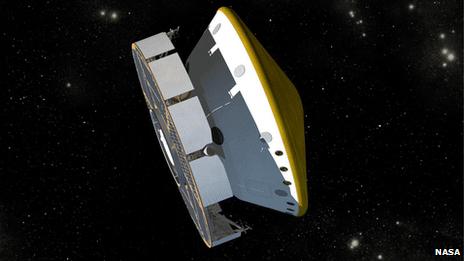

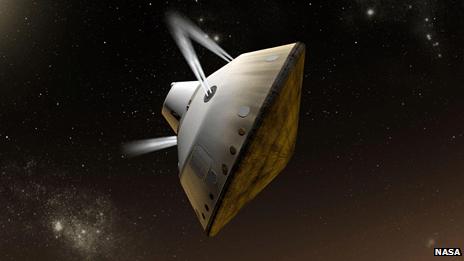

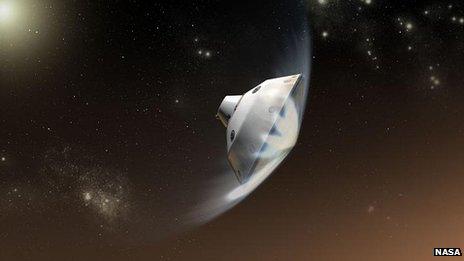

Step by step: How the Curiosity rover landed on Mars

As the rover, tucked inside its protective capsule, approached Mars, it dumped the disc-shaped cruise stage that had shepherded it from Earth

The capsule hit the top of the atmosphere at over 20,000km/h. It ejected ballast blocks and fired thrusters to control the trajectory of the descent

Most of the entry vehicle's energy was dissipated in the plunge through the atmosphere. The front shield was expected to heat to more than 2,000C

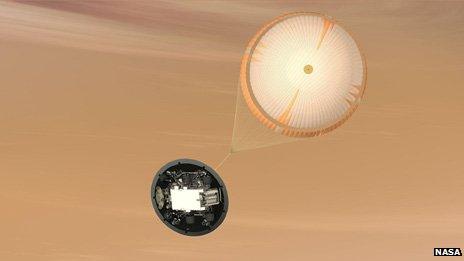

The parachute deployed when the capsule was still more than 10km above the ground but still moving at supersonic speed

A key event was the dropping of the heatshield. This permitted imaging and radar instruments to monitor the approaching surface

At about 1.5km above the ground and still moving at 80m/s, the rover and its sky crane dropped away from the parachute and capsule backshell

Rockets on the skycrane slowed the descent to about 0.75m/s. Cords spooled the rover to the surface. The cords were cut and the crane flew to a safe distance

The rover is now on the surface but is not expected to start moving until September. Its drive is now being planned by scientists

The best data on just how well the parachute performed is probably the picture of the canopy acquired by the overflying MRO satellite.

This extraordinary image shows the chute gently lowering the rover, which by that stage was still tucked away inside the backshell of its capsule.

"It's got its inflated shape perfectly," said Devin Kipp, another EDL team member from JPL.

"You can see the dark area at the top which is the vent that allows some air to escape. The shape is exactly what we expected to see. And you don't see any apparent damage. There are no holes visible; there's no tearing visible."

The final phase of EDL saw the rover drop out of the backshell and ride its rocket-powered crane to the ground.

The rover's cameras caught sight of a feature on the horizon that is not in later images

After spooling Curiosity to the surface on nylon cables, this crane then retreated to the rear of the vehicle and crashed at the safe distance of 600m.

Remarkably, the engineers think they can see the dust plume from this impact in low-resolution pictures taken by Curiosity just 40 seconds after touchdown.

The plume appears as a smudge in the thumbnail images, explained Steve Sell, the JPL team member responsible for the powered flight phase of the rover's descent.

"The evidence we have that this is something that we've caused is the fact that the same camera took another image 45 minutes later - that artefact is not there. And we do know the artefact is real because it appears in multiple hazcam images from the rear of the rover," he said.

Curiosity had a slight error (250m) in its understanding of where it was as it entered the atmosphere, but two main reasons are being given for why it overshot the bulls-eye by 2.4km.

One is errors that arose as a result of a late steering manoeuvre by the capsule intended to correct the course of the descent. This banking manoeuvre lifted the vehicle slightly and sent it long. The second is suspected to be tail winds which pushed Curiosity further down range than expected.

Nonetheless, there is huge satisfaction that the landing system performed as well as it did, and there is high confidence that given the opportunity again, the accuracy of landing could be improved still further.

"We flew this right down the middle. It's absolutely incredible to have worked on a plan for so many years and then just see everything happen exactly as it should," said Steve Sell.

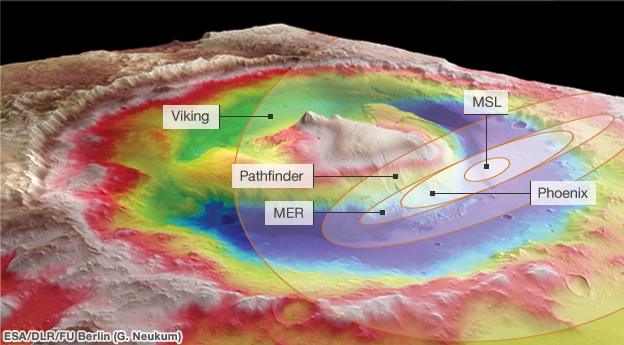

Engineers define an ellipse in which they can confidently land

Successive landings have become ever more accurate

Viking's ellipse was 300km across - wider than Gale Crater itself

Phoenix (100km by 20km) could not confidently fit in Gale

Curiosity's landing system allowed it to target the crater floor

The rover's projected landing ellipse was just 7km by 20km

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published9 August 2012

- Published8 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012

- Published5 August 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published4 August 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published26 November 2011

- Published24 November 2011

- Published22 July 2011