Nasa's Curiosity rover prepares to zap Martian rocks

- Published

This 7cm rock is about to become the first object on Mars to be zapped by Curiosity's laser instrument

Nasa's Curiosity rover is getting ready to zap its first Martian rock.

A small stone lying just to the side of the vehicle at its landing site on the floor of Gale Crater has been selected as a test target for the ChemCam laser.

The brief but powerful burst of light from this instrument will vaporise the surface of the rock, revealing details of its basic chemistry.

Dubbed N165, the object is not expected to have any science value, but should show ChemCam is ready for serious work.

"I'd probably guess this is a typical Mars basalt - basaltic rocks making up a large fraction of all the igneous rocks on Mars," Roger Wiens, the instrument's principal investigator, told BBC News.

"A basalt, which is also common under the ocean on Earth, typically has 48% silicon dioxide and percent amounts of iron, calcium and magnesium, and sodium and potassium oxides as well. We're not expecting any surprises," said the Los Alamos National Laboratory researcher.

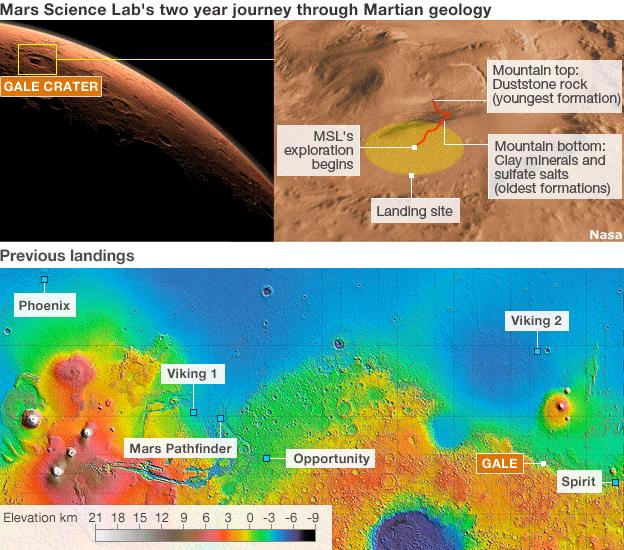

Curiosity, external touched down in its equatorial crater two weeks ago.

Hot spot

Its mission is to investigate the rocks at its landing site for evidence that past environments could have supported life.

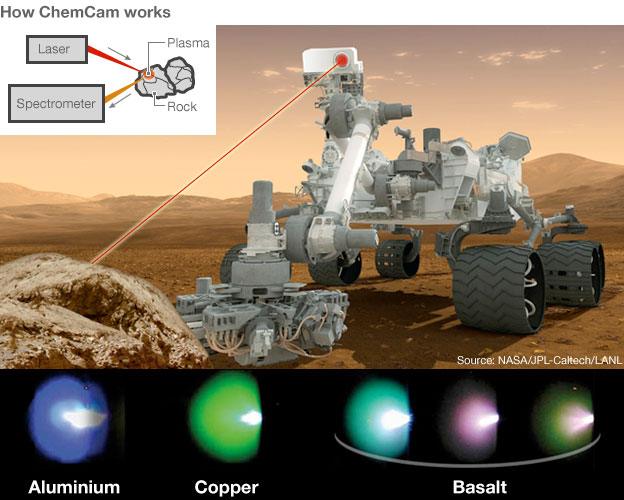

The rover carries a suite of instruments for the purpose, but its Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) experiment has probably garnered most attention because nothing like it has ever been flown to Mars before.

ChemCam sits high up on the rover's mast from where it directs a laser beam on to rocks up to 7m (23ft) away.

The spot hit by the infrared laser gets more than a million watts of power focused on it for five one-billionths of a second.

This produces a spark that the instrument observes with a telescope. The colours tell scientists which atomic elements are present in the rock.

ChemCam is going to be a key part of the process of selecting science targets during Curiosity's two-year mission.

If the laser shows up an interesting rock, the vehicle will move closer and deploy its other instruments for a more detailed investigation.

Fire marks

Assuming the test with the 7cm-wide N165 object goes well, ChemCam will move on to its first science target.

This will be rock exposed on the ground next to the rover by the rocket-powered crane used to lower the vehicle to the crater floor.

Goulburn Scour: The descent crane blew away pebbles and grit to expose underlying rock

Exhaust from this descent stage scattered surface grit and pebbles to reveal a harder, compact material underneath.

The crane made four scour marks in the ground - two either side of Curiosity. These have been dubbed Burnside, Goulburn, Hepburn and Sleepy Dragon.

The names, all related to fire, are taken from ancient rock formations in Canadian North America.

Goulburn Scour will be zapped by ChemCam.

"There's bedrock exposed beneath the soil with interesting patterns of colour," said John Grotzinger, Curiosity's project scientist.

"There're lighter parts; there're darker parts, and the team is busy deliberating over how this rock unit may have formed and what it's composed of. We'll aim the ChemCam [at Goulburn Scour], as well as taking even higher resolution images."

The science team has decided to send the rover to the intersection of three geological terrains

Curiosity has not moved since landing on 6 August (GMT). That is about to change.

The rover is going to roll forward briefly to test its locomotion system in the next few days. A reverse manoeuvre is planned, also.

Researchers want eventually to drive several kilometres to the base of the big mountain at the centre of Gale Crater to study sediments that look from satellite pictures to have been laid down in the presence of abundant water.

This journey to the foothills of Mount Sharp is going to have to wait a few months, however, because the science team intends first to go in the opposite direction.

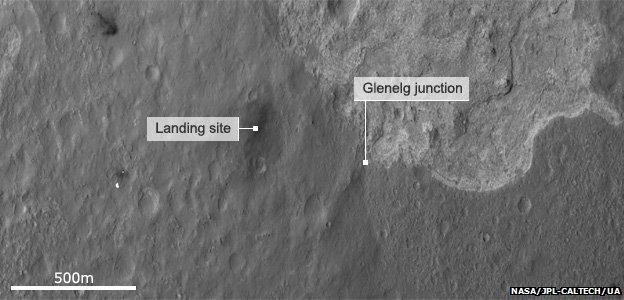

Several hundred metres to the east of Curiosity's present position is an intersection of three geological terrains.

Again, this location has been given a name - Glenelg. And, again, it is taken from the geology of North America.

The intersection is intriguing and a good place to compare and contrast with the bedrock exposed in Goulburn Scour.

In addition, it may provide access to older, harder rocks. These could make for a first opportunity for Curiosity to use its drill.

"Even though it is in the opposite direction from the path to Mount Sharp, it's the one place we can go to to capture a lot of the information that's persevered in our landing [location]," Prof Grotzinger told BBC News.

The laser focuses the energy of a million light bulbs on an area no bigger than a pinprick for a few billionths of a second

This heats the surface of the target rock to high temperatures, exciting the atoms present into producing a flash of light

A telescope and camera system observes the spark (plasma) and feeds the light signal to the rover's body via a fibre optic cable

Three spectrometers slice the light into its component colours. Every chemical element has a distinctive light signature

ChemCam can determine not only which atomic elements are present in the target rock but also their abundances

The laser can also burrow through dust or a weathered coating to see the true chemistry of Martian rocks

ChemCam will be the busiest instrument on Curiosity, helping to select the most interesting objects for investigation

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published14 August 2012

- Published13 August 2012

- Published11 August 2012

- Published9 August 2012

- Published9 August 2012

- Published8 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012