Nasa's Curiosity rover 'sniffs' Martian air

- Published

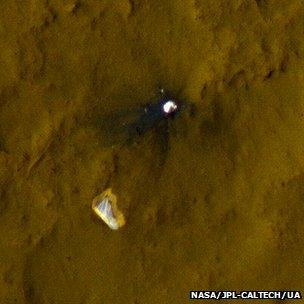

The blue patches in this false colour image are the scour marks left by the rover's rocket lander system

Nasa's Curiosity rover has measured the Red Planet's atmospheric composition.

The robot sucked the air into its big Sample Analysis at Mars (Sam) instrument to reveal the concentration of different gases.

The Sam analysis is ongoing but no major surprises are expected at this stage - carbon dioxide will dominate.

CO2 is the chief component of the Martian air, as found by the Viking probes in the 1970s and the Phoenix lander in 2008.

Of keener interest will be whether a signal for methane has been detected by Curiosity.

The gas has recently been observed by satellite and by Earth telescopes, and its presence on the Red Planet is intriguing.

Methane should be short-lived and its persistence suggests a replenishing source of some kind - either biological or geochemical. It is hoped Sam can shed light on the issue.

The results from this first test could be announced next week, said Curiosity deputy principal scientist Joy Crisp, but she cautioned that it would be some time before definitive statements could be made about the status of methane on Mars.

"When Sam is at its best it can measure various parts per trillion of methane, and the expected amounts based on measurements taken from orbit around Mars and from Earth telescopes should be in the 10 to a few 10s of parts per billion," she told reporters.

"But it's so early in the use of Sam, which is a complicated instrument, and we have to sort through the data."

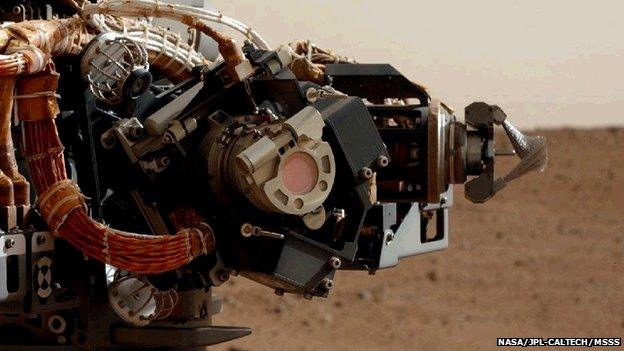

The turret is pictured by one of Curiosity's mast cameras. The pink disc is the lens cover on Mahli. The brushes at far right are used to remove dust from rocks under investigation

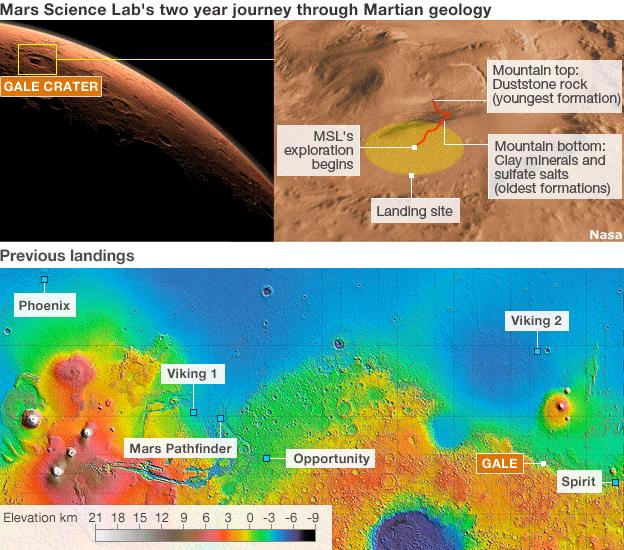

Curiosity - also known as the Mars Science Laboratory, MSL - has now driven more than 100m from the location on the floor of Gale Crater where it landed a month ago.

A new picture from the overflying Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft shows its progress.

MRO has also acquired a new view of Curiosity's descent parachute and capsule backshell

"You can see the rover with the white deck on top and the black wheels, and you can see our tracks behind us," explained mission manager Mike Watkins.

"We're about a football field or so away from the touch-down point - from Bradbury Landing."

Curiosity is heading to a point dubbed Glenelg by scientists.

This is about 300m further to the east from its current position. Satellite pictures point to Glenelg being an intersection of three distinct types of rock terrain. Researchers think it will be a good place to start to characterise the geology of Gale Crater.

The rover's arrival at the junction is still some weeks away, however.

Arm exercises

Engineers have parked the vehicle for a few days to practise using the 2m-long robotic arm. This carries a 30kg tool turret on its end and the mission team needs to learn how to move the device in the weaker gravity conditions that exist on Mars.

"Mars has about 38% of Earth gravity," said Matt Robinson, the lead engineer on Curiosity's arm.

"Under Earth gravity, the arm sags to a certain position. On Mars, if you were to command the arm to the exact same joint angles, the turret would be at a higher position than it was on Earth.

The 30kg tool turret and robotic arm move in a slightly different way in Mars' gravity

"To compensate, we have flight software that does the mathematics to position the arm lower to recreate the exact same pose of the turret with respect to the hardware on the rover.

"So a big part of this exercise is to verify that flight software is doing that compensation properly," he told BBC News.

Once the arm check-out is done, Curiosity will pick up the pace to get to Glenelg.

En route, the rover will watch for an early opportunity to test its turret instruments on a rock.

This will involve putting the "hand lens" known as Mahli (Mars Hand Lens Imager) close to the test object.

Mahli is essentially a close-up camera that can resolve rock minerals down to the size of a grain of talcum powder.

The other turret instrument engineers want to see in action is APXS, an X-ray spectrometer that can determine the abundance of chemical elements in rocks.

Also in line to make its debut soon is the turret's scoop mechanism (Collection and Handling for Interior Martian Rock Analysis, or Chimra). The robot arm will pick up a sample of soil and deliver it to the labs inside the rover body for analysis.

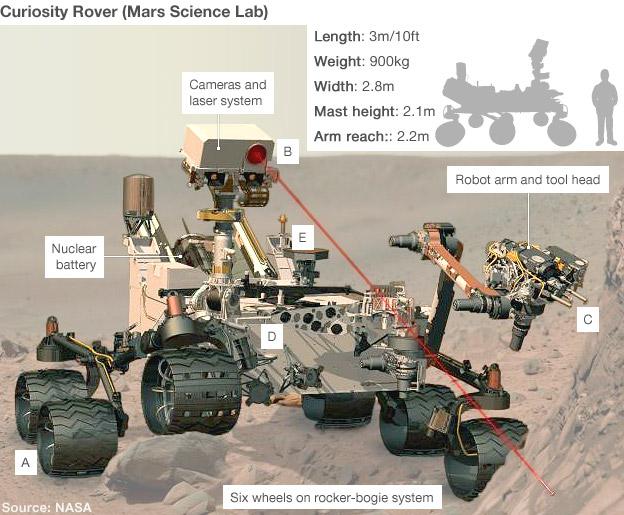

(A) Curiosity will trundle around its landing site looking for interesting rock features to study. Its top speed is about 4cm/s

(B) This mission has 17 cameras. They will identify particular targets, and a laser will zap those rocks to probe their chemistry

(C) If the signal is significant, Curiosity will swing over instruments on its arm for close-up investigation. These include a microscope

(D) Samples drilled from rock, or scooped from the soil, can be delivered to two hi-tech analysis labs inside the rover body

(E) The results are sent to Earth through antennas on the rover deck. Return commands tell the rover where it should drive next

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published30 August 2012

- Published28 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published23 August 2012

- Published21 August 2012

- Published20 August 2012

- Published20 August 2012

- Published17 August 2012

- Published14 August 2012

- Published13 August 2012

- Published11 August 2012

- Published9 August 2012

- Published9 August 2012

- Published8 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012