Creating new life - and other ways to feed the world

- Published

How best to feed a growing population in a changing climate is fiercely debated with many new and emerging research fields hoping to provide a solution.

Estimates suggest that food production will have to increase by at least 60% by 2050 to feed a rapidly increasing population, which is expected to top nine billion.

The UK government has announced it will put £160m into agricultural industries "to deliver sustainable, healthy and affordable food for future generations".

Associate professor of crop genetics Sean Mayes says there are many reasons why producing enough food will be a "significant challenge".

"It's not a case of just doubling up what we're doing, because there isn't the land to do it. There isn't one solution and there never could be. We have to pursue as many strands as we can," he told BBC News.

Here are six ideas that scientists believe could help.

Crop yields

As global temperatures rise, scientists predict that flooding and drought will continue to affect food production. Combined with limited land on which to grow food, this means finding ways to be more efficient is becoming increasingly urgent.

A team has recently discovered a drought protecting chemical that could protect crops from high temperatures.

Plants treated with quinabactin (right) did not wilt after 14 days

The chemical, "quinabactin", mimics a naturally occurring hormone in plants that helps them to respond to stresses such as heat.

"When you spray it on plants it delays wilting, reduces water loss and improves stress tolerance," says Sean Cutler from the University of California Riverside, US, who led the research.

The chemical should be easy to produce cheaply in large quantities, he adds. And although it reduces growth, this could be a necessary cost.

"Drought is a major source of crop loss every year so the need for innovations like this is only going to get stronger," he says.

"Spraying a chemical is one strategy but there are a lot of different approaches being pursued in parallel. It's likely there will be better crop yields under adverse conditions in the future, as these approaches converge."

Printing food

Technology companies are developing increasingly efficient ways of printing everyday objects.

Now printing food is becoming a reality. Nasa is experimenting with printed food, external which could feed crews on deep-space missions. Another company, Modern Meadow, announced it can print artificial meat, and a team from Exeter University has also already printed chocolate.

Carlos Olguin, from technology company Autodesk, which helps design 3D software, says such technologies will soon come together "into a 3D printing ecosystem that will involve food, but will also involve drug printing and organ and tissue printing".

"In order to be able to solve the bigger problems it's still far away, but on the other hand we have an automated assembly production line that's producing goods layer by layer, and we've been doing that for decades."

Printed food could one day replace food deliveries on space missions

Producing life from scratch

The field of synthetic biology involves assembling artificial genes to create new life. It's still in its infancy but already some pioneering new findings could have far reaching applications.

It's essentially where nature is treated like engineering, where single artificial genes assembled on a computer form the building blocks of synthetic DNA. The UK government has recently announced it will pump £60m into the field.

A new strain of yeast has also been made by a team at John Hopkins University, US, where it added vitamins into the organism. When the yeast is baked into bread, it is enriched with Vitamin C.

Now scientists are on an even more ambitious project. They are building the world's first synthetic yeast which could massively increase the organisms productive potential.

Carlos Olguin says synthetic biology and 3D printing could work together in the future to provide the tools needed to add new functions in biology, whether for energy or food.

"We are working in the 3D bio-printing community to eventually create an underlying platform from which cross-pollination occurs more seamlessly. At that point we'll start to see much bolder initiatives."

Long forgotten grain

The Bambara groundnut is a very drought tolerant crop

Humans rely on very few plants to feed more and more people, with wheat, rice and maize providing over 60% of our diets.

Scientists in Malaysia are currently looking at some "forgotten" food grains, some from hundreds of years ago, which "show a remarkable drought tolerance and ability to grow in very poor soil", says Sean Mayes from Nottingham University, UK, who is currently working in Malaysia.

Taking these traits and applying them in commercial strains could help produce crops that cope better in a changing climate.

"We are looking to try and diversify what we grow food from. Essentially, we're extremely dependent on a very limited number of species worldwide.

"There are a lot of millets that are similar to grain crops which have evolved under low-input agriculture. Some of these are actually among of the most drought-tolerant crops," he explains.

The Bambara groundnut, for example, was a major crop grown in Africa before colonial powers introduced the peanut.

But the lack of resources and infrastructure in developing countries means there are many challenges ahead.

"Just producing enough food has to be the starting point. Looking at what we're producing, and looking for better alternatives, has the potential to help the stability of food production."

Genetically Modified food

Companies in the US have produced GM food for many years

Instead of cross-breeding crops, which can take years, genetic modification (GM) seeks to artificially tweak the genetic make-up of food in a laboratory. Scientists essentially take a desirable gene from one organism and insert it into another.

The UK government recently announced that GM crops could be safer than conventional plants. Most supermarkets have banned GM food but meat from animals fed on GM crops is now widely sold.

The majority of people are supportive of GM, says Dr Mayes, "but there's a vociferous minority of people who are against it in principle".

"We don't have the luxury of saying we won't use GM as an option because there may be circumstances where we come across an agricultural problem that we cannot solve conventionally, because there isn't the variation in the germplasm that allows us to bring in traits like disease-resistance.

"The perception people have is that GM is an all-or-nothing approach, but really GM is a part of conventional breeding in a sense. It can solve certain problems but it has to be in a background that's adapted to the environment through conventional breeding."

...and the incredible shrinking man

"A plant in a greenhouse grows very tall, but once it goes outside it will collapse as it cannot support itself."

That's the analogy Arne Hendriks, the conceptual artist behind the Incredible Shrinking Man, external, used when proposing that in the right environmental conditions, humans could shrink, or rather, they could evolve a smaller form.

"We are on a constant life support system in a culture of over-consumption that we have created. We are consuming much more sugar, protein and fat than we were at the beginning of the 19th Century," says Mr Hendriks

"This is not evolution. The growth we are seeing now is much more cultural."

Prompted by his own height of nearly 2m and observing how much more food he needs than someone smaller than him, he now encourages debate with experts in various fields to highlight the impact of people gradually becoming taller.

"If you look at science within nature, I'm convinced we can shrink. The tallest people in the world are much taller than the shortest. It's culturally and biologically programmed into us to want to grow taller."

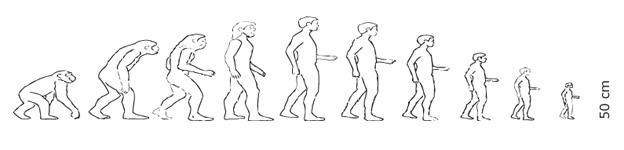

How an ancient human species may have shrunk as a result of island dwarfism

Evolving to be small is not a new notion in science. In fact, a species of a human-like creature on the Indonesian island of Flores is believed to have shrunk as an adaptation to its environment. One theory is that the metre-high small-brained hominin, nicknamed "the hobbit", evolved from the larger-bodied Homo erectus.

- Published11 October 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published13 September 2012

- Published2 December 2010