'Supermodel' Goce satellite to fall to Earth

- Published

- comments

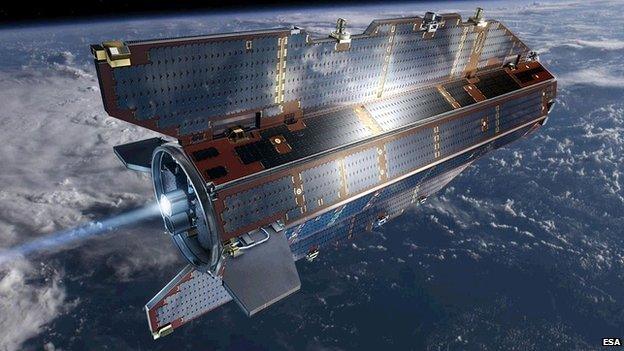

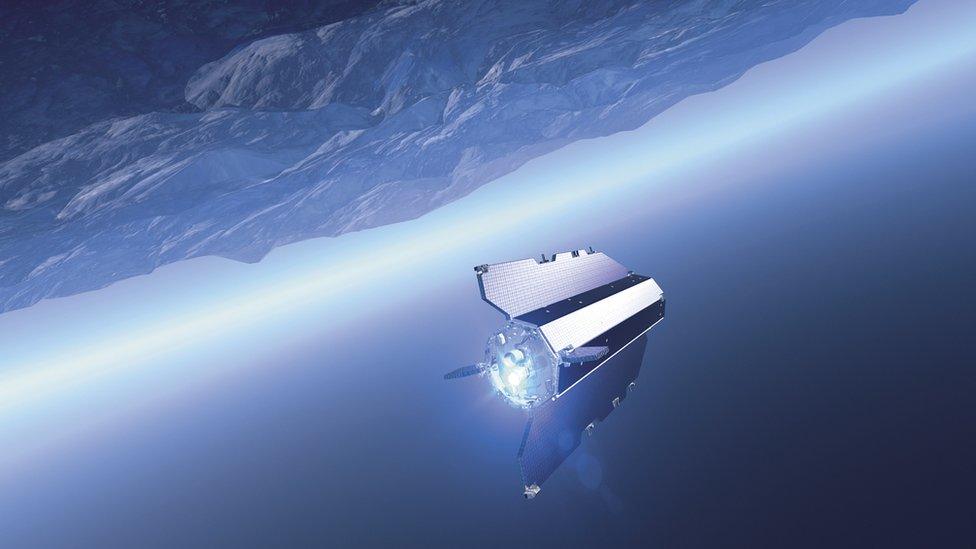

Goce uses an electric engine to push it through the wisps of air just 224km above the Earth's surface

The European Space Agency (Esa) is preparing for the fiery fall to Earth of its Goce gravity-mapping satellite.

The sleek spacecraft is flying just 224km above the planet, but its special electric engine that maintains this altitude is about to run out of fuel.

Current estimates suggest this could occur anytime between the end of this month and the start of November.

When it does, the one-tonne Goce will plunge rapidly through the atmosphere, burning up as it descends.

"Some satellites take decades to come back after finishing operations; we will re-enter in no more than three weeks," says Esa mission manager Dr Rune Floberghagen.

Modelling work indicates that perhaps up to 25% of the spacecraft may survive all the way to the surface.

Prof Reiner Rummel: "We now have a very good knowledge of ocean circulation"

But given the proportion of the Earth covered by ocean, it is highly likely that this debris will fall harmlessly into water.

There have been much bigger satellites making uncontrolled re-entries in recent years, such as Nasa's six-tonne UARS spacecraft in 2011 and the 13-tonne failed Russian Mars probe, Phobos-Grunt, last year.

Nonetheless, Goce's imminent descent is interesting on a number of fronts.

To start with, it represents the first uncontrolled re-entry of an Esa satellite in more than 25 years. The last was the magnetosphere mission Isee-2, which came back in 1987.

Another reason is that the rapid fall in just a couple of weeks after engine shut-off will be a good test for the systems used to monitor such events.

And it is also noteworthy because this will be a re-entry of a spacecraft that incorporates a lot of advanced materials.

Satellite manufacturers are increasingly using composites in their designs, and some of these will be more resistant to the forces that would ordinarily incinerate traditional components.

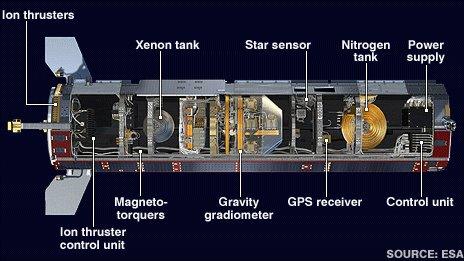

Goce, for example, made use of a carbon-carbon structure in its gradiometer.

This gave the instrument the necessary stiffness and stability to make delicate measurements of Earth's gravity field, but it also made for an extremely robust construction.

Dr Rune Floberghagen: "Carbon-carbon will be resistant to the heat load during re-entry"

"The major part of what survives to the surface will be the core instrument," says Dr Floberghagen.

"From the original mass which we have now in space, we have estimated that about 25%, about 250 kilos, will reach the surface, and these 250 kilos will be distributed over between 40 and 50 fragments."

The fragments' different sizes and masses mean they will likely impact the surface - be that land or water - in a narrow footprint some 900km (560 miles) long.

Parts of the gradiometer instrument will survive to the surface

It is simply not possible at this stage to say precisely when or where the debris fall will occur. More definitive statements will have to wait until experts have had a chance to study the degradation of Goce's orbit in its final days and hours.

The Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, external - the global forum on "space junk" - has chosen Goce as its special study project for 2013. This means large numbers of tracking and surveillance facilities around the world will be activated to monitor the gravity mission's descent to Earth.

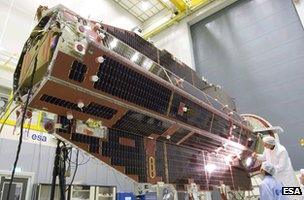

Goce was built in Italy where it was referred to as the "Ferrari of satellites"

This effort will start in earnest once Goce's ion engine depletes its xenon fuel tank.

The engine is essential to counteract the effects of atmospheric drag in its super-low gravity-mapping orbit. When the thrust stops, air molecules will act to pull Goce downwards.

Engineers are expecting the engine to die around 16/17 October, give or take two weeks.

There are no hazardous materials aboard like the hydrazine propellants used on many spacecraft. To fully passivate Goce before re-entry, all engineers have to do is switch off its transmitter. This will ensure the tumbling spacecraft does not interfere with other satellite communications.

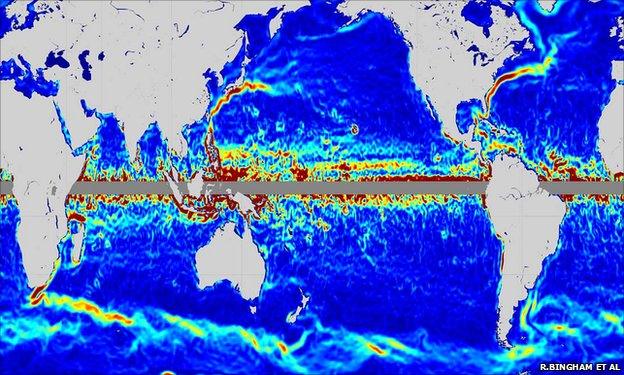

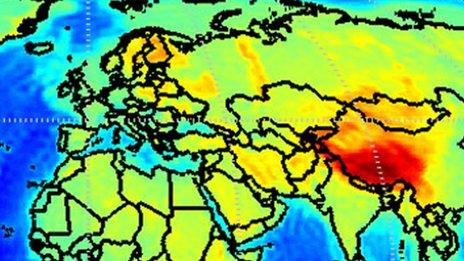

Goce has had a spectacular four-year mission. Its data has been used to build the most precise map ever obtained of the subtle variations in gravity across the surface of the Earth. This fundamental information is being used to improve our understanding of how the oceans move, and to frame a universal system to measure height anywhere on the planet - to name just two major applications.

Built from Goce data: To understand how ocean currents move you need to understand the role of gravity

Goce, of course, is famous for its looks, which are quite unlike any other satellite in operation today.

"Italian colleagues call it the Ferrari among all satellites and this is true because it is the fastest, and because it had to be built like an aeroplane to minimise external effects. This makes it an aesthetically beautiful satellite," says Prof Reiner Rummel from the Technical University of Munich, Germany, and a key figure on the Goce science team.

- Published10 March 2013

- Published19 November 2012

- Published14 July 2012

- Published12 March 2012

- Published31 March 2011

- Published21 December 2010