Arctic sea ice volume holds up in 2014

- Published

Cryosat looks for areas of open water (leads) to help gauge sea-ice thickness

Arctic sea ice may be more resilient than many observers recognise.

While global warming seems to have set the polar north on a path to floe-free summers, the latest data from Europe's Cryosat mission suggests it may take a while yet to reach those conditions.

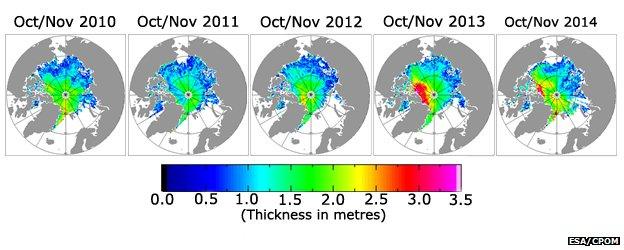

The spacecraft observed 7,500 cu km of ice cover in October when the Arctic traditionally starts its post-summer freeze-up.

This was only slightly down on 2013 when 8,800 cu km were recorded.

Two cool summers in a row have now allowed the pack to increase and then hold on to a good deal of its volume.

And while the ice is still much reduced compared with the 20,000 cu km that used to stick around in the Octobers of the early 1980s, there is no evidence to indicate a collapse is imminent.

Cryosat has funding to take it through 2017, but there is currently no planned successor

"What we see is the volume going down and down, but then, because of a relatively cool summer, coming back up to form a new high stand," said Rachel Tilling from the UK's Nerc Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM) at University College London (UCL).

"So, what may be occurring here is a decline that looks a bit like a sawtooth, where we can lose volume but then recover some of it if there happens to be a shorter melt season one year," she told BBC News.

The British researcher is presenting her work this week at the American Geophysical Union's Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

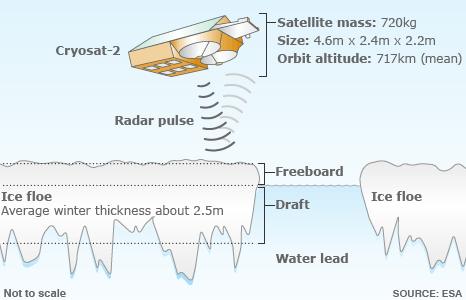

Cryosat is the European Space Agency's (Esa) dedicated polar monitoring platform.

It was sent up with a sophisticated radar system that enables scientists to work out the thickness of the sea ice covering the Arctic Ocean.

In the three years following its launch in 2010, the satellite saw a steady decline in autumn volume at the end of the summer melt.

The deep lows in this short series were 5,300 and 5,400 cubic km in 2011 and 2012, respectively. But then came the bounce back, with colder weather over the following two years resetting the minimum.

Indeed, Cryosat's five-year October average now shows pretty stable volume - even modest growth (2014 is 12% above the five year-average).

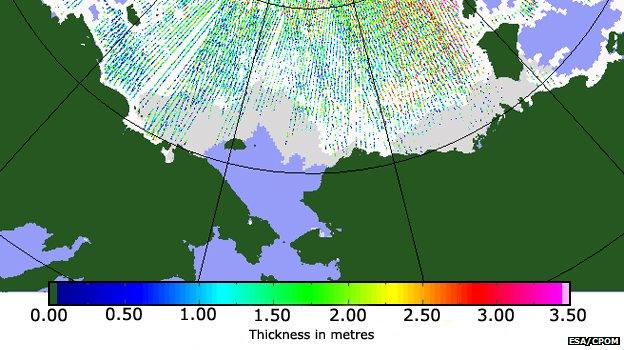

Cryosat's view of sea-ice thickness

What Tilling and colleagues see in the data is a very strong link between autumn thickness and the degree of melting in a year.

"You might think, for example, that wind conditions would be important because they can pile the ice up and make it less susceptible to melting, while at the same time exposing more water to freeze," the University College London researcher explained.

"But we've looked at this and other factors, and by far the highest correlation is with temperature-driven melting."

Long term that looks bad for the Arctic because average temperatures are climbing.

However, the Cryosat team cautions against extrapolating limited observations to predict future trends in Arctic sea ice.

Far more data is required, over a much longer period of time.

Cryosat: Delivering operational services

Point measurements of sea-ice thickness collected in the past month

Bright white area denotes sea-ice extent at the start (9 November)

Light grey shows the increase in extent by the end (8 December)

Information is useful for maritime and other actors in the Arctic

Scientists would like this information to be acquired by Cryosat.

But the Esa mission is currently categorised as a one-off scientific venture with no planned successor.

And although it has funding until 2017 and fuel reserves to work even longer, there is always the risk it could suffer a major hardware failure.

That is why Tilling and colleagues are using AGU to start a conversation about a follow-on mission.

The obvious solution would be for the European Commission to pick up the new satellite as part of its Copernicus programme.

This is a fleet of Esa-developed Earth-observing spacecraft known as the Sentinels, which are being rolled out over the next few years.

But to be included in this group, Cryosat would have to demonstrate its utility in delivering operational services - not just climate data. And that is what scientists now aim to do over the course of the next few months by delivering products such as ice maps for ship navigation.

"It's estimated that economic growth in the Arctic region will be worth $100bn over the next two decades," said CPOM director Prof Andy Shepherd from Leeds University and UCL.

"Now that Cryosat can deliver near real-time observations of sea-ice thickness that agree to within 1% of the climate-quality measurements, which are not rapid enough for operational purposes, Arctic nations will be able to make sure that any future maritime activities are done with safety and care."

Satellite altimetry: How to measure sea-ice volume

Cryosat's radar has the resolution to see the Arctic's floes and leads

Some 7/8 of the ice tends to sit below the waterline - the draft

The aim is to measure the freeboard - the ice part above the waterline

Knowing this 1/8th figure allows Cryosat to work out sea-ice thickness

The thickness multiplied by the area of ice cover produces a volume

Volume - not area - is the best guide to the status of Arctic sea ice

Cryosat's measurement technique works in autumn, winter and spring

Melt ponds on the ice make a mid-summer assessment very difficult

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 October 2014

- Published22 September 2014

- Published19 May 2014

- Published16 December 2013

- Published11 December 2013