Gaia space telescope plots a billion stars

- Published

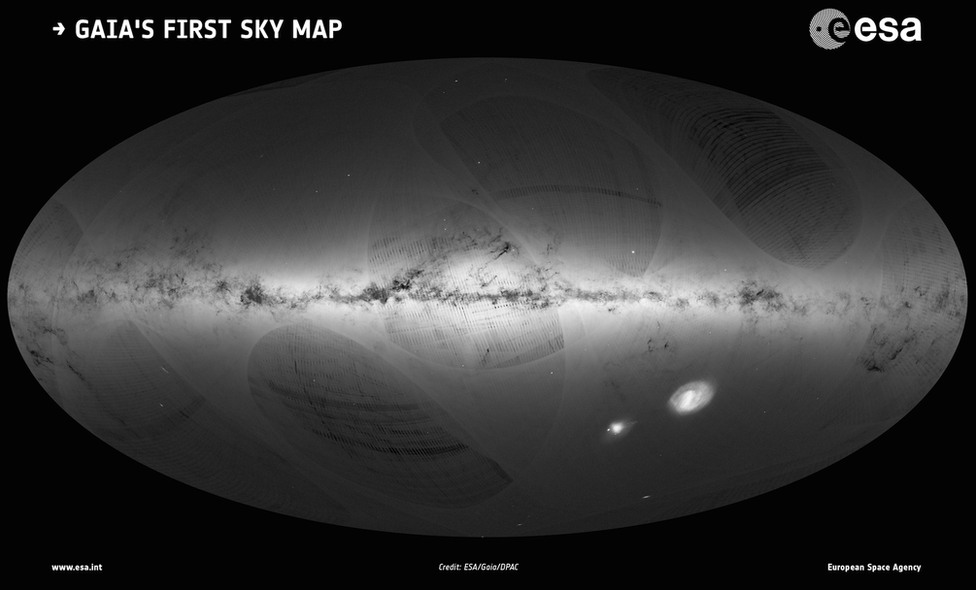

The most precise map of the night sky ever assembled is taking shape.

Astronomers working on the Gaia space telescope have released a first tranche of data recording the position and brightness of over a billion stars.

And for some two million of these objects, their distance and sideways motion across the heavens has also been accurately plotted.

Gaia's mapping effort is already unprecedented in scale, but it still has several years to run.

Remarkably, scientists say the store of information even now is too big for them to sift, and they are appealing for the public's help in making discoveries.

To give one simple example of the scope of Gaia: Of the 1.1 billion light sources in Wednesday's data release, something like 400 million of these objects have never been recorded in any previous catalogue.

"You're imaging the whole sky in basically [Hubble] space telescope quality and because you can now resolve all the stars that previously maybe looked as though they were merged as one star at low resolution - now we can see them," explained Anthony Brown from Leiden University, Netherlands.

An animation of the Milky Way galaxy as seen from the Gaia spacecraft.

Gerry Gilmore from Cambridge University, UK, was one of the mission's proposers. "Gaia is going to be a revolution," he said. "It's as if we as astronomers have been bluffing up until now. We're now going to see the truth."

A web portal has been opened, external where anyone can play with Gaia data and look for novel phenomena.

When a group of schoolchildren showed the BBC how to do it last week, they stumbled across a supernova - an exploded star.

Artwork: Gaia tells us there may be 2-3 times more stars in the Milky Way Galaxy than we thought

The European Space Agency (Esa) launched its Gaia mission in 2013.

Its goal was to update and extend the work of a previous satellite from the 1980s/90s called Hipparcos.

This observatory made the go-to Milky Way catalogue for its time - an astonishing chart of our cosmic neighbourhood.

It mapped the precise position, brightness, distance and proper motion (that sideways movement on the sky) of 100,000 stars.

Gaia, with its first release of data, has just increased that haul 20-fold.

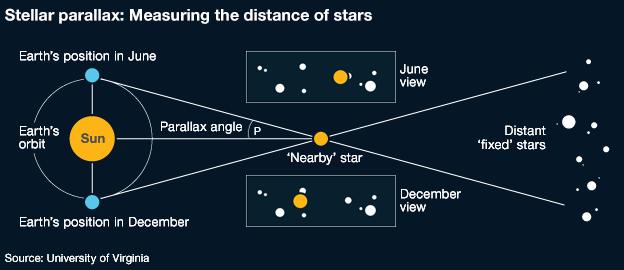

Gaia's imperative - To work out how far it is to the nearest stars

As the Earth goes around the Sun, relatively nearby stars appear to move against the "fixed" stars that are even further away

Because we know the Sun-Earth distance, we can use the parallax angle to work out the distance to the target star

But such angles are very small - less than one arcsecond for the nearest stars, or 0.05% of the full Moon's diameter

Gaia will make repeat observations to reduce measurement errors down to seven micro-arcseconds for the very brightest stars

Parallaxes are used to anchor other, more indirect techniques on the 'ladder' deployed to measure the most far-flung distances

It is a function of the leap in technology, of course.

The new mission actually carries two telescopes, which it scans across the Milky Way from a location about 1.5 million km from Earth.

The telescopes' mirrors throw their captured light on to a huge, one-billion-pixel camera detector connected to a trio of instruments.

It is this ultra-stable and supersensitive optical equipment that Gaia uses to pick out its sample of stars with extraordinary confidence.

The called-for specification was to get to know the brightest objects' coordinates down to an error of just seven micro-arcseconds.

This angle is equivalent to the size of a euro coin on the Moon as seen from Earth.

In addition to their position and proper motion, the stars are having their physical properties analysed by Gaia.

Its instruments are acquiring details such temperature and composition. These are markers needed to help determine the stars' ages.

Not all of this information can be gleaned at once. It will take repeat viewing, but by the end of five years of operations the 100,000 stars fully profiled by Hipparcos should become at least a billion in the Gaia catalogue. That is a conservative estimate, however.

If one thing is clear from the new data it is that Gaia is seeing many more fainter stars than anyone anticipated. Once the project is complete it could have plotted 2-3 billion light sources.

Gaia - The discovery machine

The Gaia space telescope was launched in 2013

Gaia will make a very precise 3D map of our Milky Way Galaxy

It is the successor to the Hipparcos satellite which mapped some 100,000 stars

The one billion to be catalogued by Gaia is still only 1% of the Milky Way's total

But the survey's quality promises a raft of discoveries beyond just the star map

It will find new asteroids and planets; It will test physical constants and theories

Gaia's sky map will be the reference to guide future telescopes' observations

Astronomers around the world will have dived into the data the moment it went live on servers on Wednesday - and for all manner of reasons.

Some of the 1.1 billion light sources will not actually be stars; they will be the very bright centres of very distant galaxies - what are known as quasars.

The nature of their light can be used to calculate the mass of all the stuff between them and us - a means, in effect, to weigh the Universe.

A good number of other data-users will be planet-hunters. By studying the way Gaia's stars appear to wobble on the sky, it should be possible to infer the gravitational presence of orbiting worlds.

"Gaia is going to be extremely useful for exoplanets, and especially systems that have the Jupiter kind of planets," said Esa's Gaia project scientist, Timo Prusti.

"The numbers are going to be impressive; we expect 20,000. The thing is, you need patience because the exoplanets are something where you have to collect five years of data to see the deviation in the movements."

By way of comparison, in the past 20 years of planet-hunting, astronomers have confirmed 3,000 worlds beyond our Solar System.

'Galactic movie'

One eagerly anticipated measurement is the radial velocity of stars. This describes the movement they make towards or away from Gaia as they turn around the galaxy.

If this measurement is combined with the stars' proper motion, it will lay bare the dynamics of the Milky Way.

It should be possible, for example, to make a kind of time-lapse movie - to run forwards to see how the galaxy might evolve into the future, or to run backwards to see how our cosmic neighbourhood came to be the shape it is today.

At the outset of the mission, scientists had hoped to get radial velocity data on about 150 million stars.

But this was thrown into doubt when it was realised soon after Gaia's launch that unexpected stray light was getting into the telescope. This made the observation of the faintest stars and their colours far more challenging.

Engineers think they understand the problem: in part it is caused by the way sunlight bends past the 10m-diameter shade that Gaia uses to keep its telescopes in shadow.

And the good news according to the scientists is that they think they can work around the difficulties.

The longer the mission runs, they believe, the closer Gaia will get to its target of 150 million radial velocity measurements - and that movie.

"Clearly, with the stray light we lost sensitivity. On the other hand, it happens to be that there are more stars than were thought before. So we're still talking about 100 million radial velocities," Timo Prusti told BBC News.

At Gaia's heart is a British billion-pixel camera-detector

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 June 2014

- Published6 February 2014

- Published19 December 2013

- Published21 August 2013

- Published10 October 2011

- Published20 July 2010