Gaia telescope's 'book of the heavens' takes shape

- Published

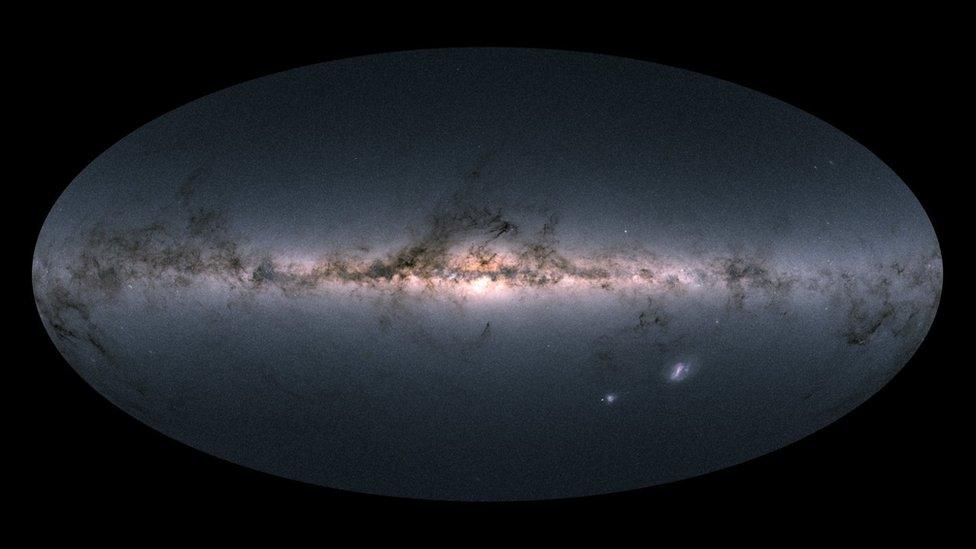

The Gaia observatory has released a second swathe of data as it assembles the most precise map of the sky.

The European Space Agency telescope has now plotted the position and brightness of nearly 1.7 billion stars.

It also has information on the distance, motion and colour of 1.3 billion of these objects.

Gaia's "book of the heavens", external will not be complete until the 2020s, but when it is the map will underpin astronomy for decades to come.

It will be the reference frame used to plan all observations by other telescopes. It will also be integral to the operation of all spacecraft, which navigate by tracking stars.

But beyond that, Gaia promises a raft of new discoveries about the properties and structure of our Milky Way Galaxy, its history and evolution into the future.

It will enable scientists to find new asteroids and planets; and to test physical constants and theories.

Gaia should even refine the techniques used to measure distances across the wider Universe, and reduce the uncertainties we currently have about the age of the cosmos.

Gerry Gilmore: "The release of this data is a transformational event"

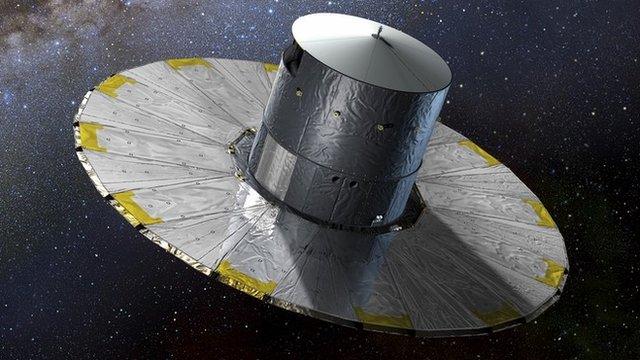

Gaia was launched in December 2013 to an orbit some 1.5 million km from Earth.

Its two identical telescopes throw their captured light on to a huge, one-billion-pixel camera detector connected to a trio of instruments.

A first tranche of measurements was released in 2016. This contained the position and brightness of "just" 1.1 billion stars, and information on the distance and motion of the two million brightest objects.

This second data release adds 600 times more stars with distances, covering a volume 1,000 times larger and all with precisions that are 100 times better.

"This is a unique moment," said leading British Gaia scientist Prof Gerry Gilmore. "This is the first time that mankind has had a significant 3D map of a significant volume of the Milky Way. It really is a breakthrough moment," he told a meeting at the Royal Astronomical Society in London.

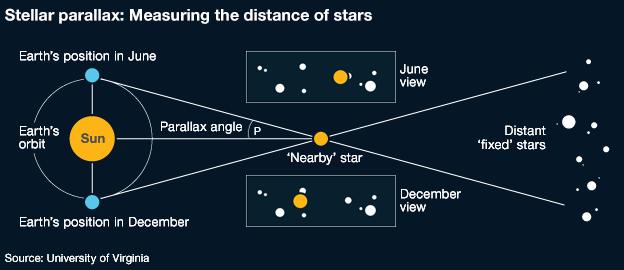

Gaia: How far is it to the nearest stars?

As the Earth goes around the Sun, relatively nearby stars appear to move against the "fixed" stars that are even further away

Because we know the Sun-Earth distance, we can use the parallax angle to work out the distance to the target star

But such angles are very small - less than one arcsecond for the nearest stars, or 0.05% of the full Moon's diameter

Gaia will make repeat observations to reduce measurement errors down to seven micro-arcseconds for the very brightest stars

Parallaxes are used to anchor other, more indirect techniques on the 'ladder' deployed to measure the most far-flung distances

Gaia measures anything that moves - which is actually everything that is out there.

It sees stars' "proper motion", which is their general track across the heavens as they orbit the galaxy. The telescope also sees their "parallax" - their apparent looping behaviour, which is a function of Earth and Gaia changing their vantage point as they circle the Sun (It is the parallaxes that yield the distances).

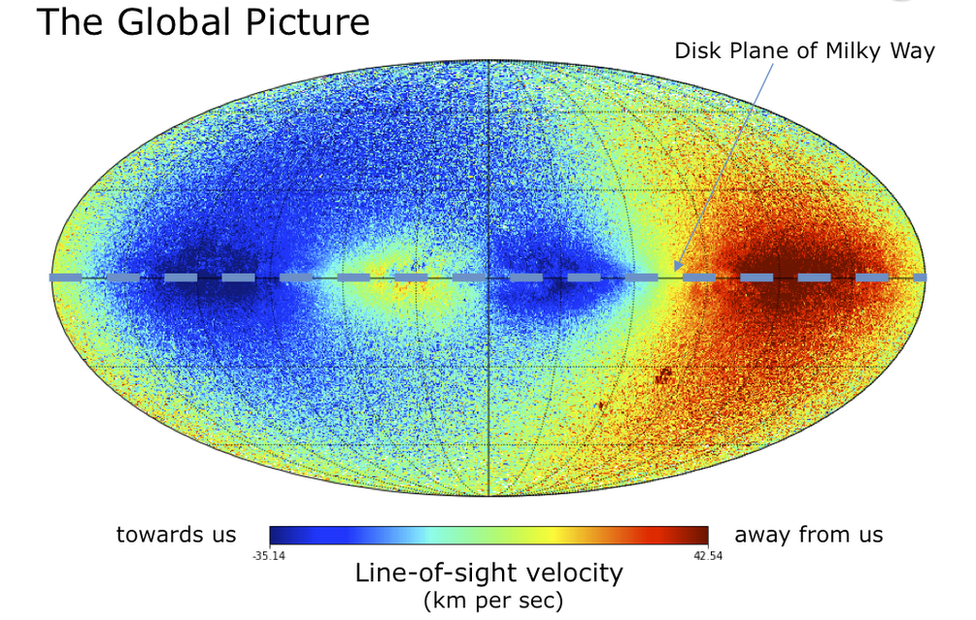

And what Gaia also sees is the stars' movement along its line of sight - their so-called "radial velocity", their true motion on the sky. Gaia delivers this data for the first time in the new release.

"We now have seven million line-of-sight velocities of stars which is more than all other measurements ever done. This is a huge sample compared with the few hundred thousand that we had before," said Prof Mark Cropper, from the Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London.

Gaia expects ultimately to plot line-of-sight motion for over 100 million stars

It is the radial velocities that allow researchers to make movies of the Milky Way, to run its life forwards and backwards in time, to determine, with the aid of other Gaia information, where stars were born and where they will likely end their days. It should be possible, for example, to find our Sun's siblings - the stars that were created in the same gas and dust cloud billions of years ago but then subsequently went their different ways.

There will be another two big data releases in the coming years. The more Gaia works, the more precise its measurements - and the more objects it will detect. There is an expectation, for instance, that tens of thousands of planets will eventually be found in Gaia's data.

The scale of the venture means there is too much information for professional astronomers to scrutinise, and amateurs and schools are being asked to get involved.

An alert system operates that throws up interesting objects that brighten or dim out of the ordinary. Some of these will be exploding stars - supernovae.

Many UK schools are now engaged in classifying these objects.

Meg Greet, a physics teacher from Eastbury Community School in the London Borough of Barking & Dagenham, said Gaia was a fantastic educational tool: "These long-term embedded enrichment projects, rather than school trips and one-off activities, are the things that make a genuine impact on our school-children scientists, helping them to develop their creativity, their questioning skills - the kind of things they need to become the scientists of the future."

- Published17 October 2017

- Published20 June 2017

- Published23 September 2016

- Published18 June 2014

- Published10 October 2011