Gaia clocks speedy cosmic expansion

- Published

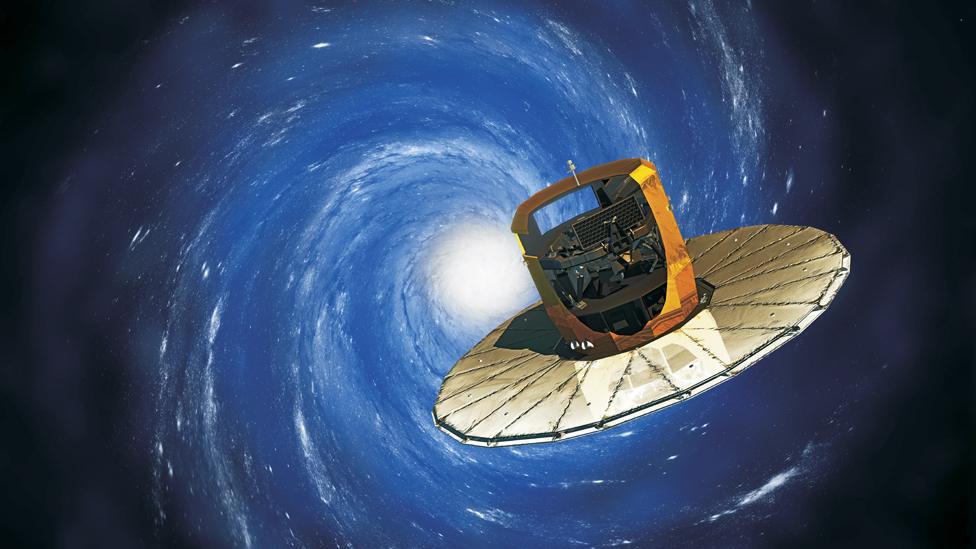

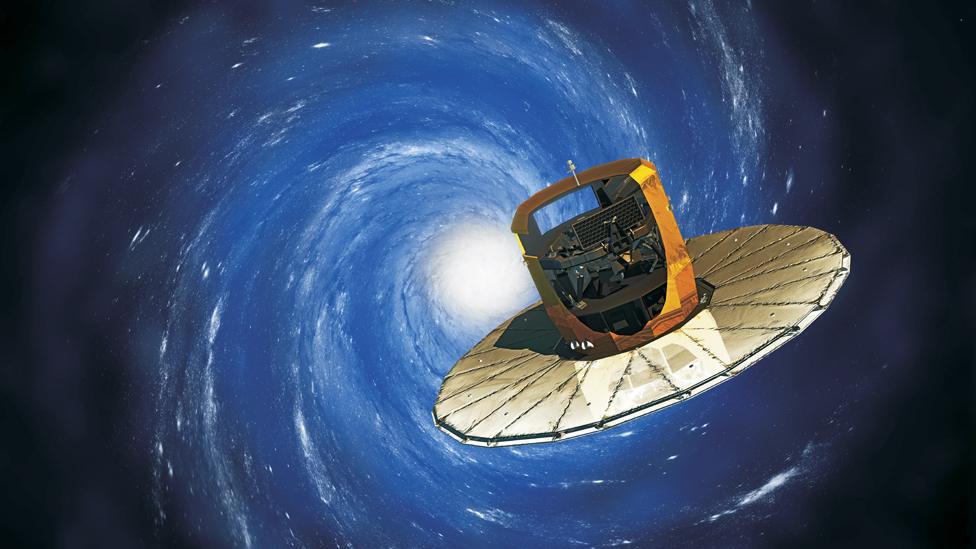

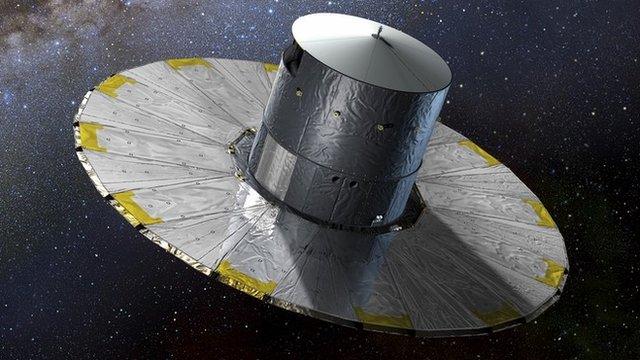

Artwork: Gaia is making the definitive map of our Milky Way Galaxy

Europe’s Gaia space telescope has been used to clock the expansion rate of the Universe and - once again - it has produced some head-scratching.

The reason? The speed is faster than what one would expect from measurements of the cosmos shortly after the Big Bang.

Some other telescopes have found this same problem, too.

But Gaia’s contribution is particularly significant because the precision of its observations is unprecedented.

“It certainly ups the ante,” says Adam Riess from the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and the Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, Maryland, US.

The inability to lock down a value for the expansion rate has far-reaching consequences - not least in how we gauge the cosmic timescale.

If the Gaia speedometer is correct, it would mean having to reduce the estimated 13.88-billion-year age of the Universe by perhaps a few hundred million years.

Cosmic 'ladder'

The European Space Agency (Esa) mission, launched in 2013, external, is making the definitive map of our Milky Way Galaxy, logging extremely accurate distances to a billion nearby stars.

Just last week, it issued the first tranche of separations to two million objects, and this information was immediately seized upon by thousands of astronomers worldwide - Prof Riess and his team among them.

The Nobel Laureate, external was interested in a specific subset of stars in the data dump known as cepheid variables.

These are pulsating stars that puff up and deflate in a very regular fashion and shine with a known power output.

They are a lower rung on the “ladder” that astronomers use to plot the separation between our galaxy and the positions of galaxies that lie billions of light-years away.

Once you know the cepheids’ exact distance, you can use their behaviour to calibrate higher rungs on the ladder - specifically, a class of supernovae, or exploded stars, that also shine in a standard way.

And by probing a sufficiently deep volume of space, it is then possible to trace the rate at which the modern cosmos is expanding.

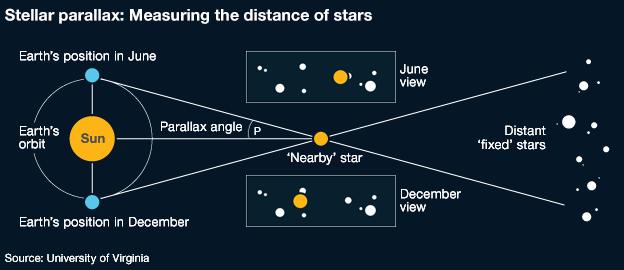

Gaia's imperative - To work out how far it is to the nearest stars

As the Earth goes around the Sun, relatively nearby stars appear to move against the "fixed" stars that are even further away

Because we know the Sun-Earth distance, we can use the parallax angle to work out the distance to the target star

But such angles are very small - less than one arcsecond for the nearest stars, or 0.05% of the full Moon's diameter

Gaia will make repeat observations to reduce measurement errors down to seven micro-arcseconds for the very brightest stars

Parallaxes are used to anchor other, more indirect techniques on the 'ladder' deployed to measure the most far-flung distances

The tell-tale is the way the light from progressively more distant galaxies becomes stretched to longer wavelengths.

This relationship is known as the Hubble Constant and tying down its value is one of the great quests in astronomy.

Working with a clutch of 212 Gaia cepheids, Prof Riess’s team gets a Hubble Constant for today’s Universe of 73.0 kilometres per second per megaparsec, external (a megaparsec is 3.26 million light-years).

Or put another way - the expansion increases by 73.0km/second for every 3.26 million light-years we look further out into space.

The number is almost exactly the same as the value the Riess group has produced using cepheids observed by the mighty Hubble telescope (73.2km/s per megaparsec). Both values have an uncertainty of just over 2%.

The problem is that these calculations come out quite a bit bigger than the one that has been determined using a very different method.

Galaxy UGC 9391: We still have much to learn about the "dark" components of the Universe

This alternative focuses on the Universe as it was just after the Big Bang and relies on what we know about the contents and the physics at work in the cosmos to predict a modern value of the expansion.

It has been done most recently using data from Esa’s Planck space telescope, which produced the most detailed description of the “oldest light” in the sky - a remnant glow of microwave radiation from the Big Bang itself.

Going with this method gives a Hubble Constant of 66.9km/s per megaparsec.

As Gaia repeats and extends its cepheid measurements in the years ahead (and it is expected to plot precise distances to at least 7,000), the confidence in its Hubble Constant calculation is likely only to increase.

This would put pressure on scientists to revise some of the components they plug into the Planck side to remove the tension that exists between the two approaches. And it is a fair bet that any such revisions are almost certainly rooted in what we know - or rather do not know - about the “dark Universe”.

This includes the unseen matter in galaxies (dark matter), the vacuum energy (dark energy) postulated to be driving an acceleration in cosmic expansion, and even as yet unidentified massive particles.

Planck mapped the "oldest light", more properly called the Cosmic Microwave Background

“Gaia is going to be a very important, really revolutionary, way to measure distances,” said Prof Riess.

“Ultimately, when Gaia is done, we ought to be able to measure the Hubble Constant to 1% precision. That’s the same precision that is predicted by the Cosmic Microwave Background. That will be really powerful.

"And if there is a discrepancy, if there's something interesting going on in the dark sector of the Universe, it should give us much better evidence of what that is,” he told BBC News.

Prof Gerry Gilmore was a proposer of the Gaia mission and is one of its senior researchers.

He said members of the Gaia science team had also run the cepheid numbers and produced a value very similar to Prof Riess’s.

Asked to list possible reasons for the discrepancy, the Cambridge University scientist raised the possibility that dark energy was time-dependent - that its influence evolves through the history of the Universe.

“Another idea that people have become quite keen on in the past year is that we actually live, by chance, in a low-density part of the Universe,” he explained.

“It’s still quite a big part of the cosmos, perhaps 1-2%, but because it’s a low-density part it’s accelerating faster than the average.”

- Published14 September 2016

- Published3 June 2016

- Published20 July 2010

- Published18 June 2014

- Published19 December 2013

- Published21 August 2013

- Published10 October 2011