Chicxulub asteroid impact: Stunning fossils record dinosaurs' demise

- Published

The seismic shockwave would have triggered a water surge, known as a seiche

Scientists have found an extraordinary snapshot of the fallout from the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

Excavations in North Dakota reveal fossils of fish and trees that were sprayed with rocky, glassy fragments that fell from the sky.

The deposits show evidence also of having been swamped with water - the consequence of the colossal sea surge that was generated by the impact.

The detail is reported in PNAS journal.

Robert DePalma is a University of Kansas doctoral student in geology

Robert DePalma, from the University of Kansas, and colleagues say the dig site, at a place called Tanis, gives an amazing glimpse into events that probably occurred perhaps only tens of minutes to a couple of hours after the giant asteroid hit the Earth.

When this 12km-wide object slammed into what is now the Gulf of Mexico, it would have hurled billions of tonnes of molten and vaporised rock into the sky in all directions - and across thousands of kilometres.

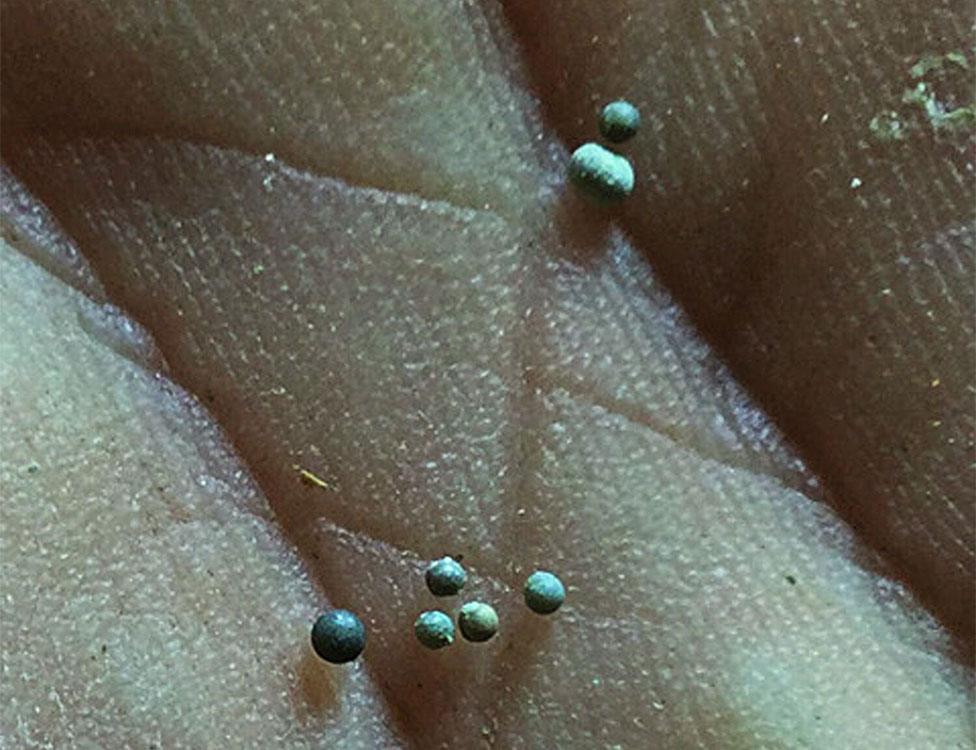

And at Tanis, the fossils record the moment this bead-sized material fell back down and strafed everything in its path.

Fish are found with the impact-induced debris embedded in their gills. They would have breathed in the fragments that filled the water around them.

There are also particles caught in amber, which is the preserved remnant of tree resin. It is even possible to discern the wake left by these tiny, glassy tektites, to use the technical term, as they entered the resin.

Fossilised fish piled one atop another as they were flung ashore by the seiche

Geochemists have managed to link the fallout material directly to the so-called Chicxulub impact site in the Gulf. They have also dated the debris to 65.76 million years ago, which is in very good agreement with the timing for the event worked out from evidence at other sites around the world.

From the way the Tanis deposits are arranged, the scientists can see that the area was hit by a massive surge of water.

Although the impact is understood to have generated a huge tsunami, it would have taken many hours for this wave to travel the 3,000km from the Gulf to North Dakota, despite the likely presence back then of a seaway cutting directly across the American landmass.

Dating the tektites gives an age for the impact - 65.76 million years ago

Instead, the researchers believe local water could have been displaced much more quickly by the seismic shockwave - equivalent to a Magnitude 10 or 11 earthquake - that would have rippled around the Earth. It is a type of surge described as a seiche, which would have picked up everything in its path and dumped it into the jumbled collection of specimens now being reported by the team.

"A tangled mass of freshwater fish, terrestrial vertebrates, trees, branches, logs, marine ammonites and other marine creatures was all packed into this layer by the inland-directed surge," said Mr DePalma.

"A tsunami would have taken at least 17 or more hours to reach the site from the crater, but seismic waves - and a subsequent surge - would have reached it in tens of minutes," he added.

Walter Alvarez pioneered the idea of an end-Cretaceous impact

The PNAS paper, which will go online on Monday, includes among its authors Walter Alvarez, the Californian geologist who, with his father Luis Alvarez, is credited with helping to develop the impact theory for the demise of the dinosaurs.

The Alvarez pair identified a layer of sediment at the boundary of the Cretaceous and Palaeogene geological periods that was enriched with iridium, an element commonly found in asteroids and meteorites.

Iridium traces are also found to be capping the Tanis deposits.

"When we proposed the impact hypothesis to explain the great extinction, it was based just on finding an anomalous concentration of iridium - the fingerprint of an asteroid or comet," said Prof Alvarez. "Since then, the evidence has gradually built up. But it never crossed my mind that we would find a deathbed like this."

Phil Manning, from the University of Manchester, the only British author on the paper, commented: "It's one of the most important sites in the globe now. You know, if you truly wanted to understand the last day of the dinosaurs - this is it," he told BBC News.

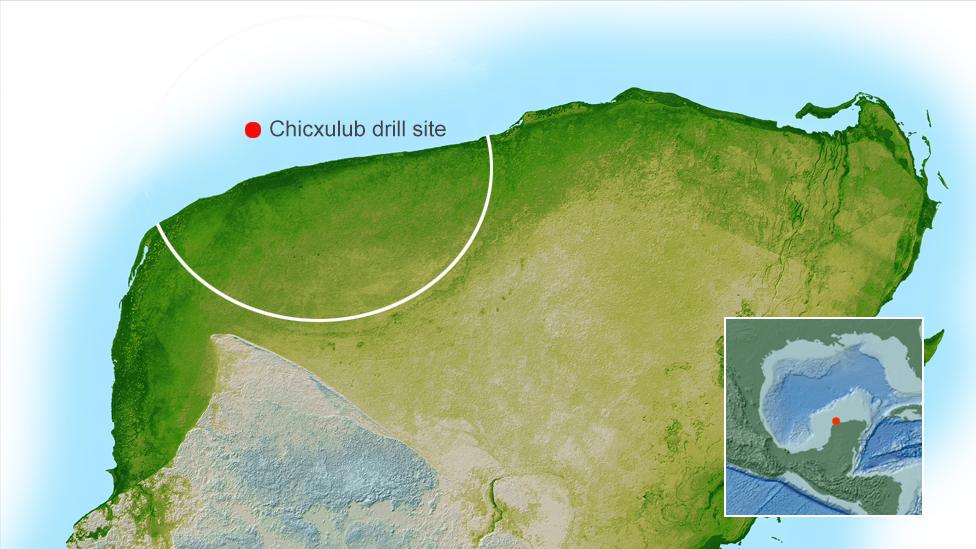

The Chicxulub Crater - The event that changed life on Earth

The outer rim (white arc) of the crater lies partly under Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula

A 12km-wide object dug a hole in Earth's crust 100km across and 30km deep

This bowl then collapsed, leaving a crater 200km across and a few km deep

Today, much of the crater is buried offshore, under 600m of sediments

On land, it is covered by limestone, but its rim is traced by an arc of sinkholes

Scientists recently drilled into the crater structure to learn about its formation

Mexico's famous sinkholes (cenotes) have formed in weakened limestone overlying the crater

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published31 October 2017

- Published15 May 2017

- Published23 March 2017

- Published13 December 2016

- Published18 November 2016

- Published7 November 2016

- Published11 October 2016

- Published25 May 2016

- Published5 April 2016