Touring a county with 'special energy' - using a 1939 guidebook

- Published

In 1939, the newly established Penguin Books published six guides to English counties, complete with touring maps, aimed at the middle-class motorist. Emma Jane Kirby has been driving around the UK with those first-edition guides in her hand to see how Britain has changed since the start of World War Two. Next stop: Somerset.

"To tell the story of Glastonbury is difficult," protests my Penguin guide's pernickety author, "so cunning is the mixture of legend and history."

For the classically trained schoolmaster, S E Winbolt, today's Glastonbury might test his narrative powers further still, and especially on market day.

I've only been strolling the main thoroughfare for 15 minutes and I've already been offered the chance to have my chakras spring-cleaned, a three-for-two deal on incense sticks and I'm now getting guidance on whether to buy a rather beautiful hand-crafted wand.

"Birch is best for you," advises Howard the heavily tattooed wand maker thoughtfully, giving me the once-over. "Nothing too powerful to start with."

Howard, who spent most of his pre-wand-making career as a psychiatric nurse at Broadmoor, agrees that back in 1939, Glastonbury market would have been unlikely to be selling wands - which he thinks is a pity, as he makes each of his with a lot of love and a fair bit of sustainable, locally sourced wood.

We glance around the other stalls with their crystals, stones and tarot-card readings and, hitting my head on a dream catcher as I turn (Howard assures me it's not unlucky) I reflect that the very essence of Glastonbury has been completely transformed over the past 80 years.

Howard shakes his head.

"Glastonbury's always had its moments," he corrects me. "It has a special energy."

Enjoying the month of May in Glastonbury

It also has a very special music festival, of course, although this year the Glastonbury Festival is in a fallow year.

Had a time machine been available to transport S E Winbolt forward into summer 2018, however, I'm not sure he would have felt he was missing out.

"No," agrees Howard. "The traffic's terrible."

Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones appeared at Glastonbury in 2013

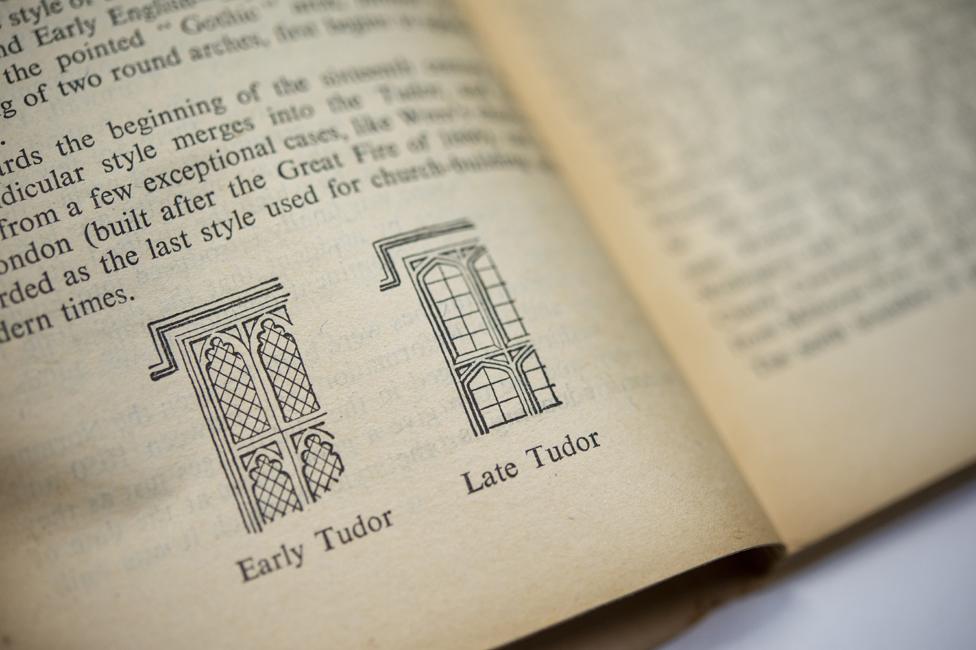

All the Penguin county guides are based around church-visiting, but Winbolt's passion for ecclesiastical architecture is perhaps in a class of its own. His pages are peppered with erudite information about north perpendicular windows, Norman towers, triple sedilia and rood-loft doorways, which he appeals to his readers to please "note" and "admire".

1939 Glossary I

Sedilia - a group of three stone seats for clergy, set in the wall of a church

Rood loft - a gallery or platform at the top of a rood screen, which in some churches separates the nave and the chancel

Chancel - part of a church near the altar reserved for clergy and the choir, often at the east end

At North Curry, he persuades me that "it is well worth making a detour" to see the church and of course he's quite right. The church of St Peter and St Paul is a bucolic gem and inside I duly "note" the effigy of the 14th Century lawyer and, in the north aisle, another of a monk creepily reduced to skeleton form.

I also note that despite their entirely positive nature, the recent entries in the visitors' book are rather few and far between. Alas for S E Winbolt, the 21st Century holidaymaker appears to be looking for something a little more thrilling than chancels and bench ends, however exquisitely carved.

"I'm going to chuck up!" screams a schoolgirl delightedly as the fairground ride on Weston-super-Mare's Grand Pier catapults her and her friends into the air. "Oh my days, this is brilliant!"

Winbolt promises that the "air of Weston is a fine tonic" but I'm already catching a waft of candyfloss, chips and burgers, with perhaps the faintest hint of… is that whelks?

Find out more

Listen to Emma Jane Kirby's report from Somerset for the World at One on BBC Radio 4

Scroll down for links to her reports from Kent, Derbyshire, Cornwall and the Lake District

Weston's tourism manager, Caroline Darlington, has the excellent idea of abandoning the rides, slot machines and zombie interactive video games to head for a quieter area by the railings at the pier's edge. There, a few querulous seagulls dive-bomb a sign that warns tourists not to feed the birds because they can be extremely aggressive. They begin to circle a sleeping sunbather in her deckchair like vultures.

"In 1939, the railway companies used to advertise Weston-super-Mare as having air like wine!" Darlington informs me as we settle on some stools looking out over the mudflats.

It wasn't only the air, the mud too was once considered to have health-giving properties

She shows me tourist information leaflets on Somerset's churches and guided heritage walks. She assures me that a few people do still ask for them but admits that today's tourist generally has different priorities.

"Your 1939 guide barely mentions children. It was about what adults wanted," she says.

"Now it's all about the family holiday. And today's children, with all the TV and advertising they're exposed to, do want a bit more than sitting on the beach staring at seagulls. They're looking for activity like the waterpark or adventure park and the fun rides."

Winbolt referred to Weston as a "most astonishing mushroom" that suddenly grows in the holiday season. And it still is.

A donkey ride on Weston beach in the cool summer of 2011...

In the first week of July, even before the school holidays, up to 200,000 holidaymakers strolled up the grand pier, possibly (or possibly not) lured by a giant poster advertising The Wurzels in concert. (What a pity Winbolt missed out on that!)

On the huge, wide sands, the promise of donkey rides has several primary school children shrieking with delight. Darlington tells me that some of the families operating the donkey rides established their businesses as far back as the 19th Century.

... and in the scorching summer of 2018

"This scene replicates exactly what you'd have seen in the summer of 1939," she laughs as we watch a barefoot little boy and girl jigging around excitedly in the saddles of Rose and Minnie.

Not quite. As the handler patiently helps the children put their sandy feet in the stirrups, I notice they thank him shyly in Russian.

Winbolt may not have predicted foreign tourism but he did fear industrial competition from overseas. Particularly when it came to the business of weaving baskets from willow shoots known as osiers.

"Women and children strip the osiers in a brake and bundle them into wads getting four pence a wad," he wrote knowledgeably. "Will the industry stand up to foreign competition?"

"Well, there are only three willow-growing businesses round these parts now," says Nicola Coates as she welcomes me to her beautiful willow farm near Taunton. "But we're still here and still very busy!" (She adds a hasty disclaimer that child labour is no longer used.)

We stroll down towards the 100 acres of beautiful willow beds with Coates's spaniel, Floss, proudly leading the way down a shady path that's animated with intricate wicker sculptures. Coates shows me the youngest of the plantation beds, which was planted last year and which she expects to last for around 15 to 20 years.

"Today we harvest with machines," she says. "In 1939, they'd have been harvesting with hooks and they'd have tidied up any problems, trimming dead bits. By doing that, they'd have got at least 30 years out of a bed. Machine harvesting has definitely shortened the life of the beds, but who wants to be out there in the depths of winter with a hook?"

Harvesting osiers on the Somerset levels in 1932

Coates explains that although foreign competition and rising labour costs contributed to the decline of the wicker industry after World War Two, it was the emergence of plastic that really hit hard. The convenience and cheapness of plastic, she says, meant that the craft of the wicker basket was forgotten. But perhaps in our Attenborough-influenced post-Blue Planet II society, I suggest, wicker could replace plastic again?

"Now that would be brilliant!" smiles Coates. "We've really adapted since 1939 - half of our crop now goes on making artists' drawing charcoal, but the biggest difference is that apart from furniture and baskets we are now making a lot of coffins.

"If you think about a pine coffin, it would take maybe over 50 years to create the planks of wood needed and another 50 to replace them. Willow coffins make a very sustainable alternative."

"On the road again, Buckland St Mary: this is the last place where the fairies were seen in Somerset," writes Winbolt. "If they followed the British in their trek westward, it seems not unlikely, because the Devon border is a short half mile away."

I'm supposed to be heading east towards Yeovil now, but am so startled by this rather whimsical entry into the guidebook by the habitually no-nonsense Winbolt that I feel forced to make a quick detour south into the folds of the Blackdown hills. I scour the sun-scorched grass in the graveyard of the beautiful Victorian church of St Mary the Virgin for signs of sprite life but find only rabbit droppings and a few sweet wrappers. Not a fairy, pixie or goblin in sight.

When I do reach "enterprising" Yeovil, Winbolt wants me to know all about leather and kid gloves.

"Gloves, as for centuries past, come from Yeovil."

The local football team, Yeovil Town, is still known as "The Glovers" but by the late 1980s the last of the glove manufacturers in the town had closed its doors, blaming cheap foreign imports. Yet one company, Pittards, which for most of the last two centuries was merely a leather supplier, has now brought glove-making back to the town - and it also makes other clothes, and bags. When it was founded, in 1826, Pittards worked only with local Somerset sheepskins, but now it sources its skins from Ethiopia. This shift began a long time ago; even 80 years ago, most Pittards leather was imported from Africa because it was recognised that the skins of the mountainous Cabretta or "Hairsheep" were more suitable for gloves.

Drying leather

"Back in 1939, we would have imported raw material but now the early processing is done overseas and we do the dyeing and finishing here," says Pittards' chief executive Reg Hankey as we watch workers on the plant floor stretching tanned leather under huge vacuum drying machines. "In '39, we would have hung the skins on a washing line to dry for at least three days - now, with these machines, it takes five minutes!"

Pittards is no longer a family business. It's now very much a global enterprise and 92% of the leather products it makes for the glove, shoe and automotive industries are exported. Although much of the production line has been automated, many of the finishing processes, such as staking [softening] and polishing, are still performed in exactly the same way they would have been 80 years ago.

"We haven't found a way of improving this method apart from with high skill," Hankey shouts to me over the deafening noise of the polishing machines, pointing out two of his workers who've been polishing leather here for 37 years. He lets me touch the cool, silky white leather that will soon be transformed into golfing gloves and explains that in September 1939, with the outbreak of war, Pittards really came into its own, developing waterproof leather for gloves worn by RAF fighter pilots.

"We used to be driven by the military requirement," he smiles. "And although we do still serve the armed forces, in this day and age we are really driven by sports requirements." He shoots me a sideways glance. "With the world that we're in at the minute, maybe that will revert back one day?"

It's a depressing thought for a holidaymaker. I imagine the tourists of 1939, their brand new orange and white Penguin guides in their hand, and I wonder whether, as they excitedly motored from place to place, the threatening cloud of impending war darkened their fun?

"People living in a region bounded by highlands are naturally tenacious of their soil and disinclined to migrate," asserts my guide. "Note how physical environment influences the folk of the Meare and Godney marshes - even today they seldom seem to quit their moors."

At the Sheppey Inn in Godney on the Somerset Levels, the fun is just starting. Loud upbeat music pours from the door and the first of the early evening drinkers is studying the draught ciders list with the knowledgeable barmaid. The same family ran the pub for 120 years in a space that was the size of what a creative estate agent might call "an occasional bedroom or study" but in 1976 the family, rather embarrassingly for Somerset, ran out of cider and the doors slammed shut.

The Somerset levels

Then, seven years ago, Lizzie Chamberlain from London and her partner Mark decided it was time to give Godney its pub back - but on a much grander scale. Lizzie looks tired as she hands me a lime and soda - the pub can now accommodate 250 diners as well as drinkers and last night they were again at full capacity. She steels herself for tonight's onslaught with a strong coffee.

"We do a lot of music nights," she laughs as I politely ask the bar staff to turn the music down a bit. "So people come from miles around and yet Godney is really on a road to nowhere. But it's turned into a lovely community pub, very much the heart of the village, with local staff and local produce… and we have an eclectic mix of people in the village now with artists and musicians, and the old villagers are living harmoniously with the new."

Lizzie introduces me to retired locals Phil Ryder and his wife, Amanda, who migrated to Godney 35 years ago and brought up three children here, including their daughter, Marigold - who is, in turn, bringing up her son here. Amanda tells me they were initially treated very much as outsiders by the villagers. But do they now feel what S E Winbolt describes as the pull of the Godney soil?

Lizzie Chamberlain, Marigold, Phil and Amanda Ryder

"This place suits me down to the ground," grins Phil showing me his hands, which are filthy with earth. "I'm reluctant to go on holiday or even into town. I don't like leaving my land and I don't like being indoors."

Amanda makes a snide aside about Phil's readiness to leave his land for last orders now the pub's reopened and the family laughs. Amanda says she rarely leaves Godney, largely because she doesn't drive and there's only one bus a week - although she notes that she's often the only passenger on that bus. (Whether this is because every other villager has a car, or - as Winbolt would have it - they have a genetic disinclination to migrate, she prefers not to speculate.)

Marigold, meanwhile, reflects that although she did leave to go to university, she found herself being magnetically pulled back to the marshes afterwards.

"l do feel a sense of belonging," she agrees. "And whenever I go to other places I like, perhaps on holiday, nowhere else really compares. In winter it's bleak and can be quite depressing but it's beautiful and people do tend to stay… or if they do go, they tend to come back."

We finish our drinks and stroll outside to sit at the coveted tables by the river for a while and we watch big, dark fish fin down deep in the clear water.

Back at Weston-super-Mare, a coach sporting a large sticker declaring that it's carrying the Cliff Richard Fan Club of Birmingham has just pulled up on the promenade. I wander over to a beach shack and treat myself to a rather grand-sounding lobster and crab burger and settle down with my guide book on the wide Weston sands for a moment of peace and reflection in the sunshine. That is when I'm mugged by a vicious swarm of seagulls, one of which snatches the luxurious fish from my fingers while its fellow gang members beat their wings in my hair until I relinquish most of the chips as well.

Chewing dejectedly on the small, rather sandy piece of bun the gulls have spared me, I open the fly leaf of S E Winbolt's Penguin guide and read that he follows two guiding principles in life: "Aristotle's energeia combined with Virgil's labor improbus."

1939 Glossary II

Energeia (Greek) - source of the modern English word "energy" but Aristotle's meaning is different... and not easily translated

Labor improbus (Latin) - steady work, as in the phrase "Labor omnia vicit improbus" from Virgil's Georgics, meaning "Steady work overcame all things"

I imagine S E Winbolt sitting on the beach here in 1939, perhaps dressed in a woollen bathing suit, a knotted handkerchief on his thinning hair to protect his head from the sun - and I fantasise about slapping him.

See also:

The guidebook that led me to a lost corner of England (Kent)

The forgotten guide that took me to another time (Derbyshire)

Touring the Lake District with an 80-year-old guidebook

'Nothing but a holiday resort?' Revisiting 1939 Cornwall

Touring a county with 'special energy' - using a 1939 guidebook (Somerset)

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.