Cambridge spies: Defection of 'drunken' agents shook US confidence

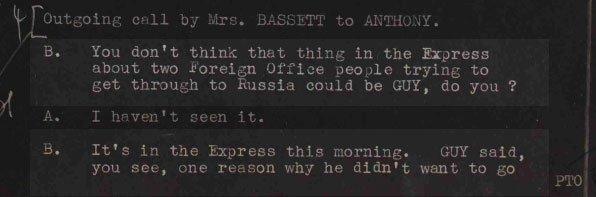

- Published

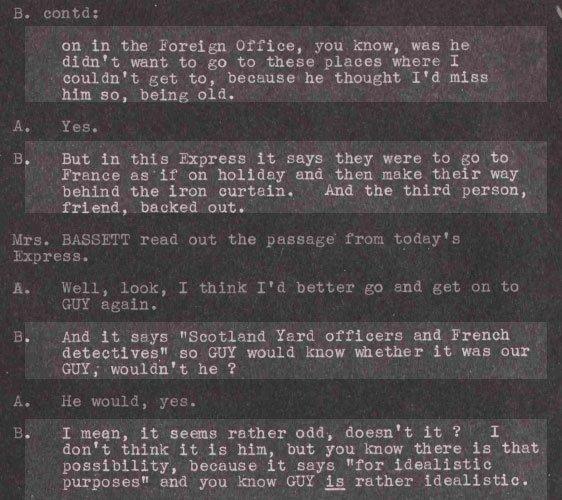

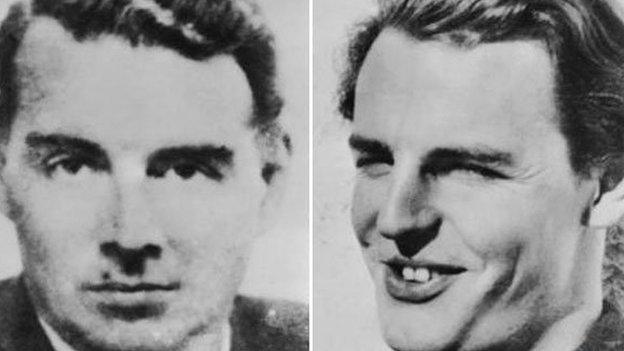

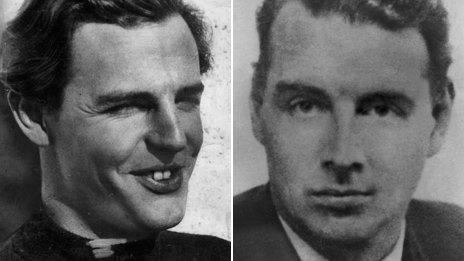

Donald Maclean (L) and Guy Burgess (R) fled to Russia in 1951

Two members of the Cambridge spy ring were so drunken and unstable that US officials were stunned they had been employed by the Foreign Office, papers released to the National Archives show.

The defection of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean to Moscow in 1951 left the US State Department's confidence in British officials "severely shaken".

Both had been involved in notorious drunken escapades, the files say.

US officials were "highly disturbed" and demanded Britain "clean house".

Burgess and Maclean were part of a group of Cambridge graduates working as double agents and passing official secrets to their spymasters in Moscow.

The files, released online on Friday, external, also reveal:

Fellow Soviet spy Anthony Blunt was used by MI5 to write to Burgess in Russia begging him not to return to the UK

Burgess's mother first learned of her son's defection in a newspaper

Kim Philby possibly hastened the fall of the spy ring - of which he was a member - by pointing out that a Russian defector had revealed that a Foreign Office source regularly reported to the Soviets

Philby was assigned to the case of a would-be Russian defector who said he had the names of dozens of British spies - and made sure the KGB got to him first

Elsewhere, an association between prominent Tory peer Robert Boothby and London gangster Ronnie Kray was the subject of an MI5 investigation

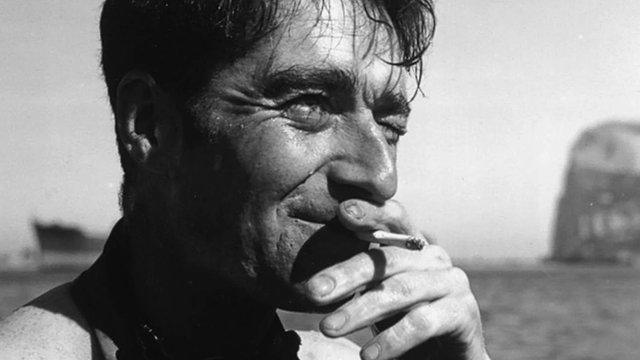

Mistakes in a Cold War spy operation in Portsmouth in which a Navy frogman, Colonel Lionel "Buster" Crabb, died

The spy ring was formed while the men were at Cambridge University

The files show that both Burgess - who had worked at the BBC, external before joining the Foreign Office - and Maclean had been involved in drunken escapades.

Maclean admitted he was a communist when he was drunk, but he was not believed, and Burgess revealed the identities of two British intelligence officers during a row in Tangiers.

They left for Russia when it looked as if Maclean's cover was about to be blown - and when Burgess's career looked to be over after he was found guilty of "serious misconduct" for drink-driving.

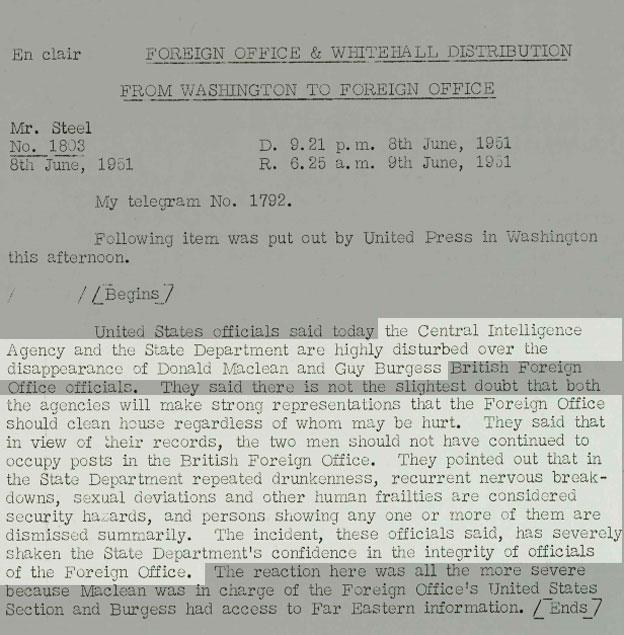

A telegram from the British embassy in Washington, in June 1951, reported that the US State Department and CIA were "highly disturbed" by the men's disappearance.

The message continued: "They pointed out that in the State Department repeated drunkenness, recurrent nervous breakdowns, sexual deviations and other human frailties are considered security hazards, and persons showing any one or more of them are dismissed summarily."

'Society scandal'

Dr Richard Dunley, records specialist at the National Archives, Kew, said the papers were the first to show the "inside story" of how the Foreign Office, Cabinet Office and secret services reacted to the shock defection.

"At the time, it was probably the biggest scandal in British society since World War Two," he said.

"It was a huge story - these hugely influential figures, suddenly going over to 'The Reds' as they were then called."

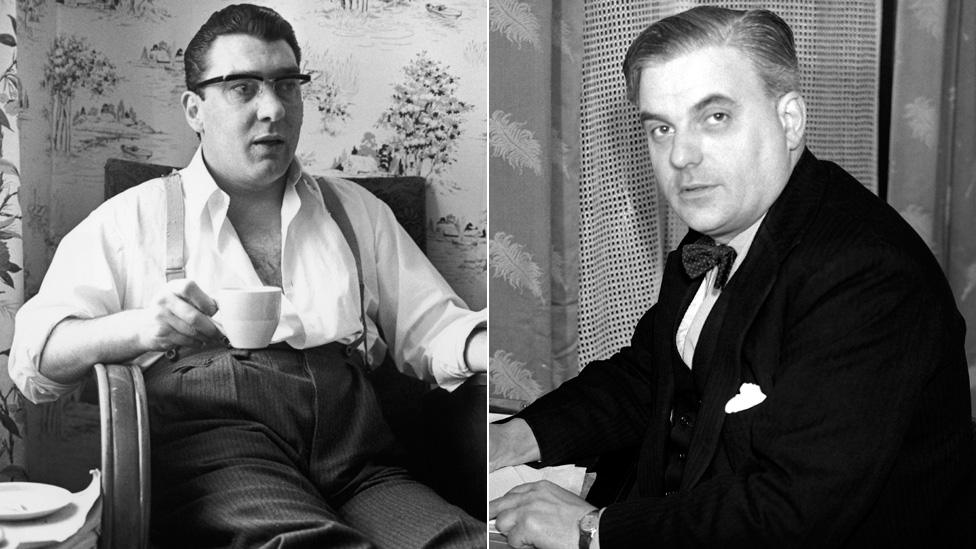

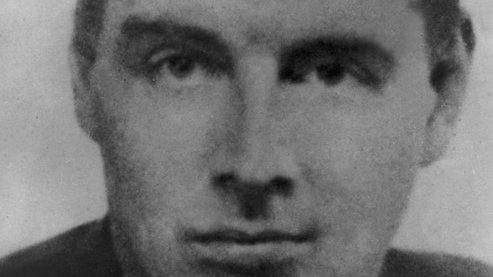

Burgess pictured around 1935, the time he was at Trinity College, Cambridge

Dr Dunley suggests Burgess and Maclean's behaviour should have raised suspicions before they suddenly left for Russia in the middle of the night.

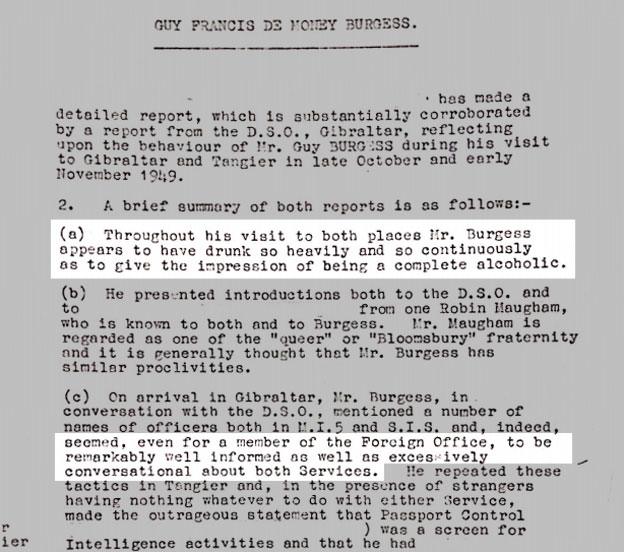

Burgess had travelled to Gibraltar and Tangiers in 1949 - a trip that his friend Goronwy Rees described as a "wild odyssey" of indiscretions.

And an MI5 representative in Gibraltar said: "Burgess appears to be a complete alcoholic and I do not think that even in Gibraltar I have ever seen anyone put away so much hard liquor in so short a time as he did".

'Too outrageous to spy'

"Both had almost breakdown-type incidents in the lead-up to their defection," said Dr Dunley.

"The idea of a relatively senior officer going around Gibraltar talking about MI5 and MI6, and who their agents were, to anyone - to modern eyes, it would seem like an instantly sackable offence."

Dr Dunley added: "In some ways, it worked well to protect him [Burgess] because everyone thought he was so outrageous there was no way he could be a Soviet spy."

Burgess's own mother also struggled to believe her son could be a spy, saying in a telephone call: "You don't think that thing in the Express about two Foreign Office people trying to get through to Russia could be Guy, do you?"

It was several years later that Burgess and Maclean surfaced in Russia.

Burgess exchanged letters with his mother from his village outside Moscow, but while boasting about his new life, there was evidence he was homesick and often "drunk and depressed", Dr Dunley said.

"There's the impression he wasn't entirely convinced by his own decision," he added.

'Mud would be slung'

In fact, the prospect that Burgess might return caused serious concern within the British government .

Not only was there relatively little evidence that could be put before a trial, due to the covert methods of information gathering used, but he was linked to many high-profile figures, including W.H. Auden, external and E.M. Forster.

In the end, Blunt - himself a member of the "Cambridge Five", external - was asked to write on behalf of MI5, pleading with Burgess not to return.

Blunt, who admitted his own treachery in 1964, knew his own loyalties would be questioned if Burgess returned.

"You would be arrested on landing - that is certain - and put on trial," he wrote.

"What the outcome of the trial would be is, of course, a matter of speculation, but on the way the whole story would be raked up again, many of your friends would certainly be called as witnesses, and mud would be slung in all directions."

In the end, neither Burgess or Maclean would return - Burgess drinking himself to death in 1963, aged 52. Donald Maclean also died in Russia, in 1983.

- Published23 October 2015

- Published23 October 2015

- Published23 February 2015

- Published7 July 2014

- Published17 January 2014

- Published18 November 2013

- Published26 October 2012

- Published30 June 2011