Operation Gomorrah: Firestorm created 'Germany's Nagasaki'

- Published

The scale of the destruction caused shock and fear across Germany

This story contains graphic images.

The centenary of the RAF not only coincides with the 75th anniversary of one of its most famous missions - the Dambusters - but also with one of its most controversial.

Kate Hoffmeister, 19, was trying to escape the furnace her Hamburg neighbourhood had become.

"I struggled to run against the wind in the middle of the street... we couldn't go on across [the road] because the asphalt had melted.

"There were people on the roadway, some already dead, some still lying alive but stuck in the asphalt. They must have rushed on to the roadway without thinking.

"Their feet have got stuck and they had put out their hands to try and get out again. They were on their hands and knees screaming."

The attack on Hamburg, Germany's second largest city, would be known as Operation Gomorrah, after the biblical city wiped out by fire and brimstone.

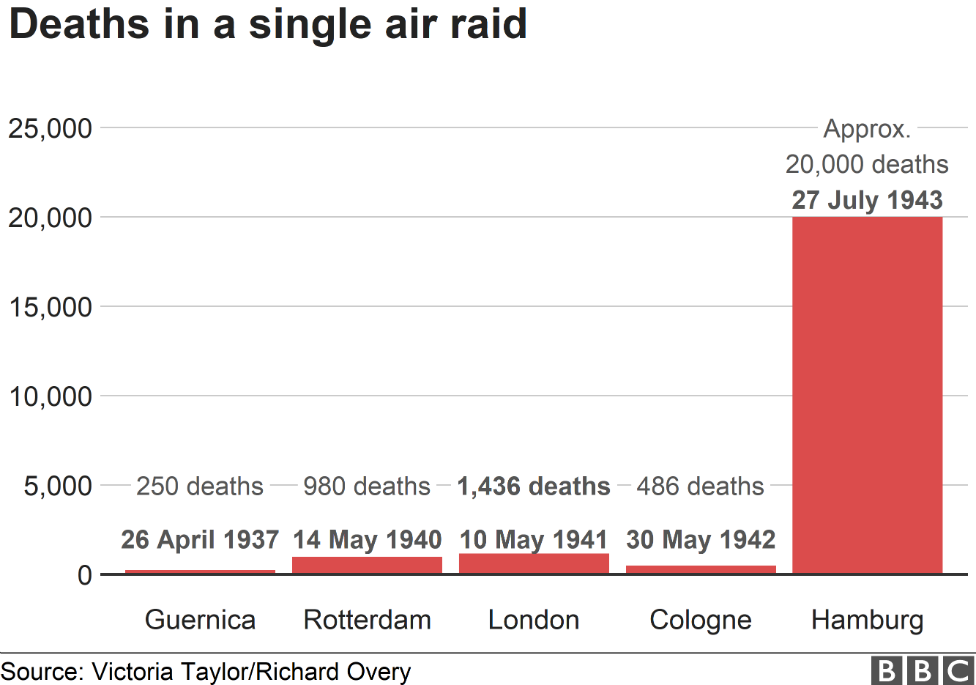

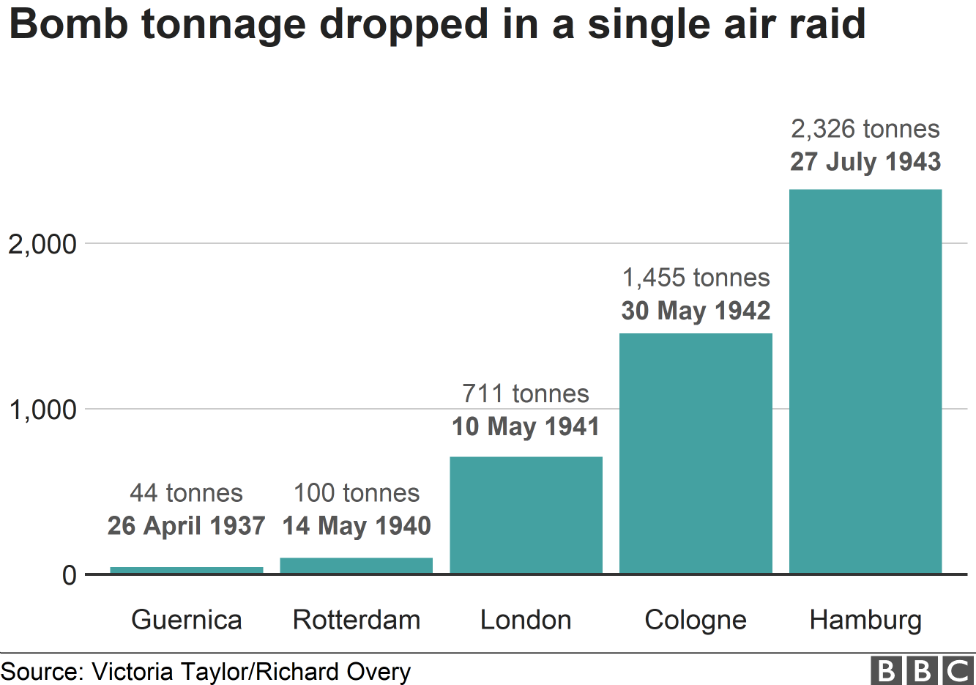

Air raids were nothing new. The agonies of Guernica, Warsaw, Rotterdam, London, Coventry and Cologne, where raids killed hundreds, were already seared on the international consciousness.

But Gomorrah in July 1943 would be on a new and terrible scale - unmatched by any other single Allied air attack in Europe during World War Two.

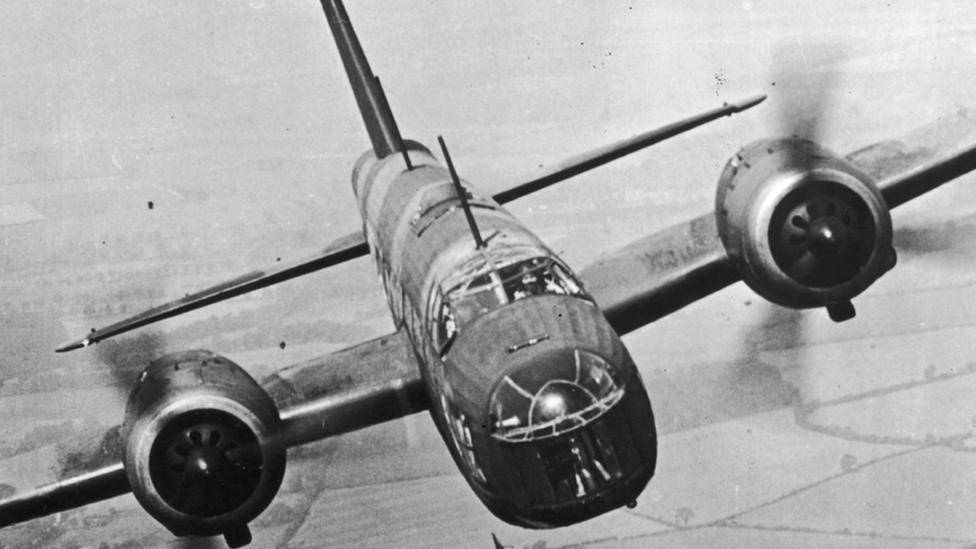

Hundreds of aircraft flew from dozens of airfields - here a Lancaster leaves RAF Syerston in Nottinghamshire

Keith Lowe, author of Inferno, a book about the attack, said: "There is in the UK a tendency to equate what happened in Hamburg and Dresden with what happened in London and Coventry.

"But Hamburg is on a completely different level - it is more comparable with what happened in Nagasaki."

Gomorrah was rooted in failure. Bomber Command's early efforts were blackly laughable, with only a tiny percentage of bombs falling anywhere near their targets.

In 1941 it was calculated it took five tonnes of bombs to kill one German. The numbers of enemy dead were almost the same as Allied aircrews lost.

This prompted a change in tactics. Specific industrial targets were mostly abandoned.

Mr Lowe said: "Hamburg was the result of a deliberate policy. In a way it would be understandable - if you can't hit, say, an aircraft factory alone, you can try and hit anything around it.

"But this went further - it stopped trying to hit the aircraft factory, it specifically targeted the workers and their families."

In 1942 a decision was taken by the War Cabinet and the Air Staff to destroy all of Germany's cities with populations over 100,000, targeting "the morale of the enemy civil population - in particular the industrial workers".

By the following year Bomber Command had enough aircraft, a single-minded leader in Arthur Harris and the technical knowledge to carry this plan out.

Mr Lowe says: "Experience and extensive testing had shown a mix of high explosives and incendiaries was the most destructive combination.

"The big bombs blocked roads, shattered water mains and, crucially, blew out windows and roofs.

"Then thousands of incendiaries could start fires to cause intensive destruction."

Aircrews were awed by the scale of destruction, indicated in this press photo of a smaller raid

Gomorrah - with eight days of bombing by the RAF and USAAF from 24 July - would prove these theories.

In the event, a number of circumstances magnified Hamburg's suffering.

Tuesday 27 July was another hot day in an already long summer and the city was tinder dry. Emergency teams were busy dealing with fires from earlier raids in the western districts.

And the RAF had a secret weapon - codenamed Window.

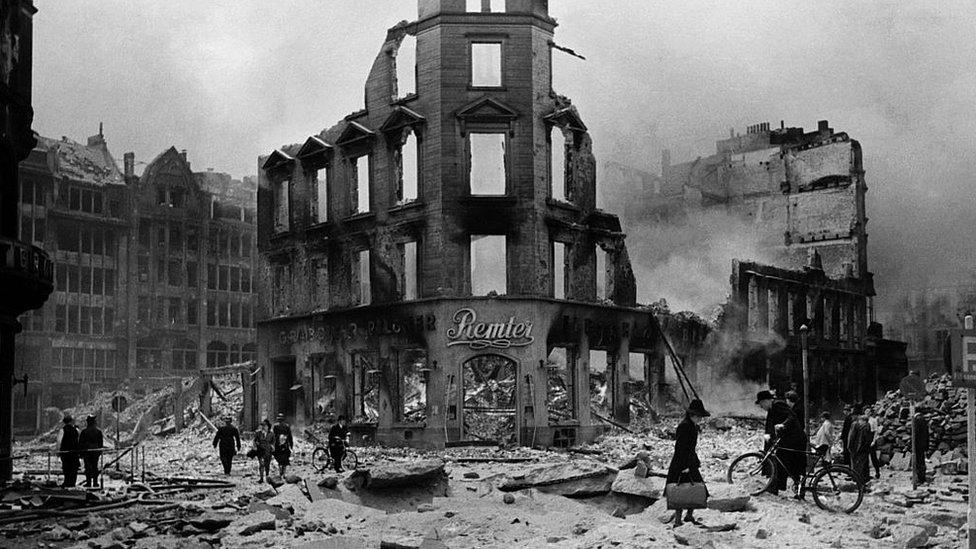

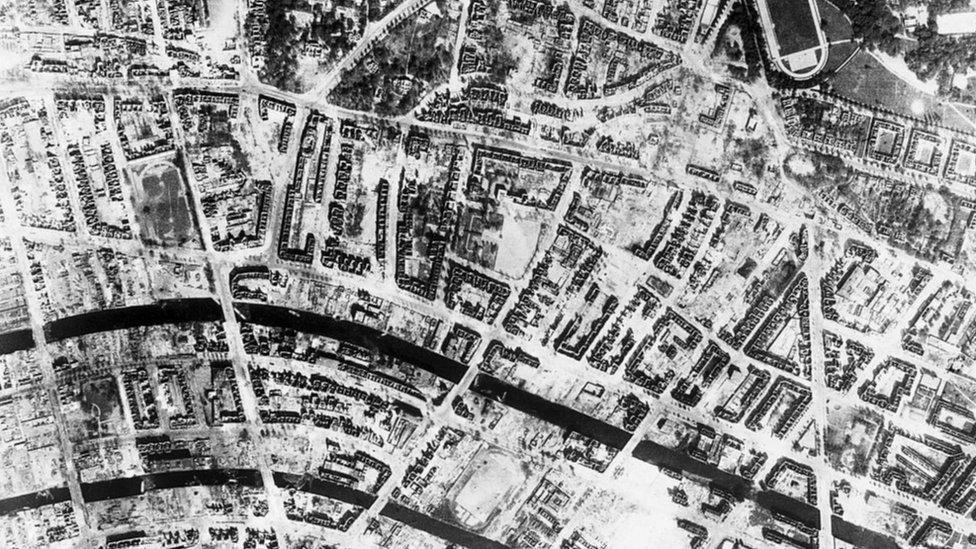

Even outside the firestorm area, large areas of the city were devastated

Tens of thousands of strips of aluminium paper were launched from planes, creating a snowstorm of reflected radar signals and effectively blinding the fearsome German defences.

Almost unhindered, at 00:55am the first of more than 720 heavily laden bombers arrived over the tightly packed workers' apartments in the east of the city.

In the next few hours, a new word was added to the dictionary of war - firestorm (feuersturm).

Heussweg, a street in central Hamburg, before the bombings

The same view in the aftermath of Operation Gomorrah

The phenomenon matched the apocalyptic name of the operation. Something akin to the wrath of God was visited on the city.

Concentrated, unchecked fires linked up to turn parts of Hamburg into a furnace. Hot air soared into the sky, sucking more from street level.

Winds reached speeds of up to 150mph (240km/h) and temperatures reached at least 800C. Wood, fabric and flesh blazed. Glass exploded, metal twisted, stonework glowed dull red.

Packed apartment blocks became shells within minutes.

Streets became tunnels of screaming hurricane-force winds - one survivor recalled a noise "like an old church organ when someone is playing all the notes at once".

Operation Gomorrah timeline

24-25 July: Night raid by about 790 RAF bombers. First use of Window

25 July: Day raid by about 120 USAAF bombers

26 July: Day raid by about 50 USAAF bombers

27-28 July: Night raid by about 780 RAF bombers. Firestorm

28 July: Evacuation of Hamburg ordered

29-30 July: Night raid by about 770 RAF bombers. Second Firestorm

2-3 August: Night raid by about 740 RAF Bombers, which were scattered by bad weather

Already stretched fire crews were overwhelmed.

They faced a "sea of fire", with clothes and vehicles bursting into flames. One described rescue efforts as like "throwing a drop of water on a hot stone".

The tornado, filled with fire, embers and debris, sucked people - especially the old and young - towards the fire.

Many Hamburg residents died together when overwhelmed by heat or struck by debris

Henni Klank fled her apartment with her husband and baby only when the curtains were on fire and the ceiling began to crack.

"At this moment something snapped in a neighbour and, caught up in a panic, he took his bed cover and wanted out.

"None of us could stop him. We saw him still, but only as a living torch carried by the firestorm, 'flying through the air'."

Cowering in a shelter, her family faced the same terrible choice as thousands of others that night: stay put and risk being buried, suffocated or even cooked, or chance the hellish conditions outside.

The damage was beyond anything previously achieved by aerial bombing

With oxygen becoming so thin candles were fading, they broke down a cellar wall to escape.

They faced a scene from the end of days.

She said: "We came out... into a thundering, blazing hell. The streets were burning, the trees were burning and the tops of them were bent [by the wind] right down to the street.

"Burning horses out of the Hertz hauling business ran past us. The air was burning; simply everything was burning."

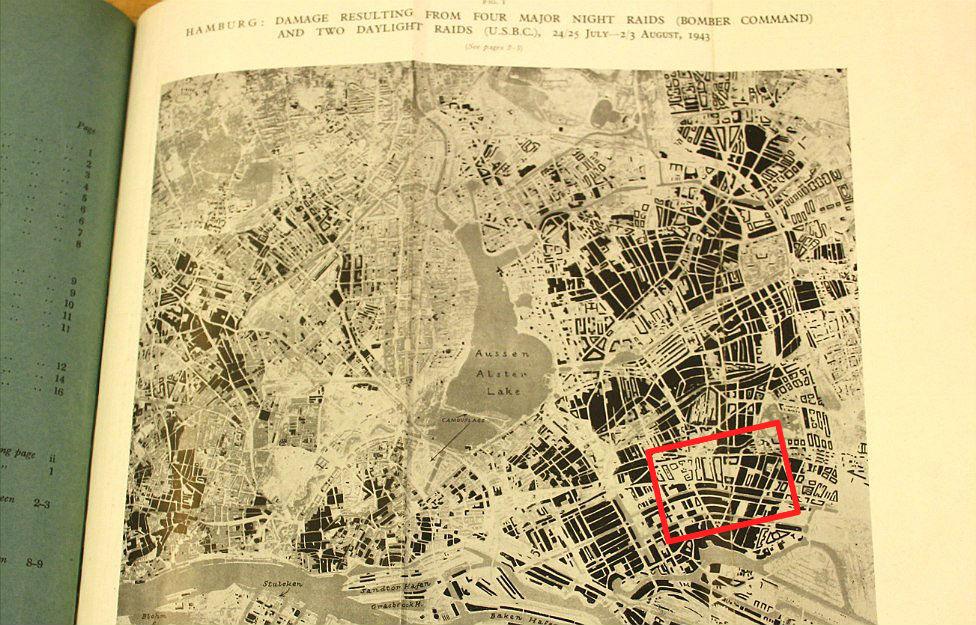

An area of about 4 sq miles (10 sq km) - roughly equivalent to the area of London from Kings Cross to the Thames, Hyde Park Corner to the Tower of London - was incinerated.

And that was just the firestorm.

Devastation was spread over roughly 12 sq miles (31 sq km). At the height of the raid 16,000 apartment buildings, with frontages of 133 miles (214km), home to nearly 450,000 people, were ablaze.

Kate Hoffmeister, who had seen the people stuck on the melted road, found herself, her mother and her Aunt Emma trapped by burning trees.

One shelter in Hamburg has been restored and serves as a museum

A grassy bank offered some shelter: "I suggested we roll down this bank... I went and I think I rolled over some people who were still alive. I lost my aunt at that point.

"By then my face and arms and legs had been burnt so badly I could only act by touch."

Thousands of feet above, RAF aircrews were elated by the success of Window and awed by the power of the raid.

Air gunner Douglas Fry recalled it as: "Brilliant, better than [earlier raids]. The fires were incredibly fierce; you couldn't see a black spot amongst this huge sheet of flame which covered acres and acres.

"We didn't know about the firestorm - we just knew the target was well alight, which meant a good raid."

Large parts of the city were reduced to smoking ruins

Flying Officer Trevor Timperley said: "The blaze was unimaginable. I remember saying to the navigator, who was engrossed with his charts: 'For Christ's sake, Smithy, come and see this. You'll never see the like of it again!'

"But Hamburg raised for me for the first time the ethics of bombing.

"I took the view so-called civilians were part of the German war machine... the only ones you are left with were the children... they were not involved, so you were left with a terrible feeling about them."

Other aircrews reported being able to feel the heat, getting soot over their aircraft and even the smell of roasting flesh.

The worst-hit areas were sealed off and survivors rehomed across the country

Operation Gomorrah ran until 3 August 1943 and involved six major raids. Estimates of the dead vary between 34,000 and 43,000.

Records show the destruction of 580 industrial plants 2,632 businesses, 379 office buildings, 24 hospitals, 277 schools and 257 government or Nazi party buildings.

Somewhere upwards of half of all homes in the city were destroyed. A million of the 1.7m population fled.

Kate Hoffmeister lost her aunt, father and two uncles, but later found she was in the same hospital as her mother.

Henni Klank and her family escaped in a boat packed with traumatised women and children, and had a last glimpse of the city covered in smoke "as if to hide the horror".

The destruction was mapped in black, while aerial photographs were also taken (the area shown below matches the red box)

But for all the cost, what was the effect on Nazi Germany's war effort?

Dr Malte Thiessen, professor of contemporary European history, says: "News of the attacks ran like wildfire. Rumours of uprisings were making the rounds, fear and panic filled other cities that saw themselves next on the 'hit list'.

"Such fears were felt up to the top, with Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels writing in his diary about the 'Sword of Damocles hovering over Germany'."

The wartime control tower at Syerston still looks out over the runways used in Gomorrah

Dr Thiessen says Hamburg was "paralysed" for months after the attacks.

"Although many arms factories and refineries were operational again in early 1944, demoralisation and destruction remained a long-term problem that also weakened war production.

"And demands to protect the home front had a practical impact, in diverting arms from the battlefields, and a psychological impact, by raising questions on the fronts about was happening to loved ones at home," he says.

Harris was triumphant. Newsreels and papers claimed "Hamburg smashed!" and trumpeted the 40,000 death toll.

St Nicholas' Church, which was gutted in the raid, now houses a museum to those who died

Mr Lowe says: "To Harris, this showed that bombing alone could end the war and he pursued this idea.

"He carried on the policy of trying to wipe out cities, through Berlin and Dresden and dozens of others, to the end of the war, despite mounting evidence that hitting specific targets was both possible and more effective."

But Hamburg proved hard to repeat. Improved defences and greater distances made the bombing campaign a costly slog. Even devastating raids like Dresden, in the last days of the war, saw fewer people killed.

You might also like:

Much of Hamburg was not rebuilt for decades and, although partially preserved, St Nicholas' Church was left as a shell.

It is in the cellar of this gutted building - which was briefly the tallest tower in the world - that a museum about the firestorm has been set up, and where the anniversary of the operation is being marked with an exhibition.

Victor Baeyens, one of the hundreds of concentration camp inmates forced to help clear the bodies and bombs from the ruins of Hamburg, wrote later the scale of destruction stunned even the prisoners.

"When listening to those horror stories we no longer broke into cheers as we did during the air raid itself.

"We were soberly thinking of the drama of mothers looking for their children and vice versa. What a curse war is."

- Published10 July 2018

- Published18 May 2018

- Published27 June 2012

- Published28 June 2012