Suitcase confirms Harry Grenville's family died in Auschwitz

- Published

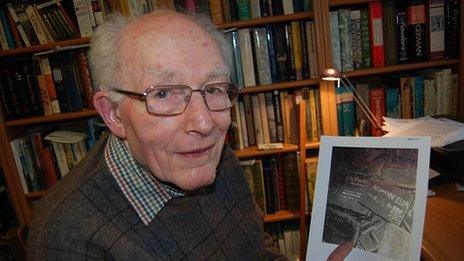

Harry Grenville escaped from Germany aged 13 and never saw his parents again

Harry Grenville has always been convinced his parents and grandmother died in Auschwitz in 1944.

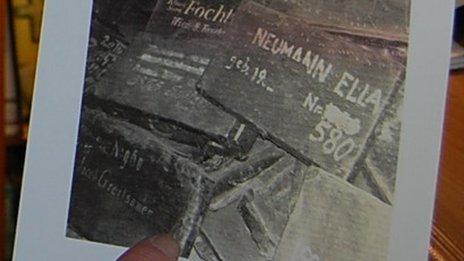

But he had never had any concrete evidence that they met their deaths in the Nazi extermination camp in Poland - until last week when, out of the blue, he received a picture featuring the suitcase his father carried into the camp.

The case, bearing the name Jakob Greilsamer, could clearly be seen in a pile at the Auschwitz Museum.

It had been taken by a Polish photographer and passed to Mr Grenville's friends in Germany. They emailed it to Mr Grenville, 86, who has lived in Dorchester in Dorset for many years.

He was only 13 when he escaped the Holocaust by being brought to England on the Kindertransport, along with his sister Hannah.

Last message

They arrived in July 1939 and were taken in by a foster family in the Cornwall town of Camelford, a time he remembers fondly as he was made part of the family and sent to grammar school.

"We were lucky," he said.

"Many other children who came were not as well treated."

The siblings remained in regular contact with their family through the Red Cross, until one last message arrived in October 1944 saying their parents were being sent east.

When the war ended Mr Grenville travelled to London to check the list of survivors from the concentration camps. His parent's names were not on there.

The name Jakob Greilsamer, is painted on a suitcase in the left bottom corner of the pile

He knew they had not survived the war, but until last week he had never had any concrete evidence that they had in fact been murdered in Auschwitz.

He said: "Out of the blue a photograph turned up with a whole lot of suitcases of victims, and the suitcases had the names of the victims painted on them.

"On this particular photograph, there, lo and behold, was my father's name."

On the picture the name "Jakob Greilsamer" is clearly visible.

Stumble stones

"It was rather an effecting sort of blow - the first evidence I have ever had of that my father, and therefore my mother and grandmother too, actually arrived in Auschwitz.

"We knew that in 1942 they were sent to a sort of internment camp. It was in former Czechoslovakia, a place called Theresienstadt.

"The last Red Cross message that ever came from them was in October 1944. The implication of that was quite clear.

"It said they were expecting to go east, and we knew what 'east' meant because all the Theresienstadt internees knew that east meant the extermination camps in Poland.

"They were moved there in these dreadful cattle trucks, from the internment camp to the extermination camps, where most of them were killed very soon after arriving.

"We only had indirect evidence before that they arrived, but now we've got it there photographically.

"There it is, 'Jakob Greilsamer', on this suitcase."

Mr Greilsamer, his wife Klara and her mother Sara Ottenheimer are now remembered with plaques on pavement blocks outside their former home in Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart, where they ran a wholesale packaging company.

Mr Grenville said: "The blocks are called Stolpersteine (stumble stones) because you are supposed to stumble accidentally upon them and remember the crimes of the Nazis.

"I attended the stone-laying ceremony along with several members of my family in 2009.

"It was a very moving event attended by quite a crowd, including the mayor.

Mr Grenville never saw his parents, Jacob and Klara Greilsamer, again after leaving for England

"I was quite overcome to think of the second and third generation after the Nazis making this effort at remembrance and reconciliation."

Mr Grenville, who was born Heinz Greilsamer, and his sister, who now lives in New York, were among 10,000, mainly Jewish, children rescued from Germany and brought to the UK in the run up to the war thanks to the Kindertransport initiative.

After the war he stayed in the UK, joined the British Army and was stationed in Cattistock, Dorset. Later he became a biology teacher and still visits schools to talk about the Holocaust.

He added: "I'm very anxious that younger generations should remember and that every effort is being made to.

"They need to be in touch and listen to actual survivors."

- Published13 November 2012

- Published22 July 2012

- Published24 October 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012

- Published8 March 2012

- Published27 January 2012