Stone marks Liverpool's first recorded black resident

- Published

The stone marks the life of a man, known only as Abell, who died in 1717

A stone commemorating the first recorded black resident in Liverpool has been unveiled more than 300 years after his death.

Records show the man, known only as Abell, was buried at St Nicholas' Church on 1 October 1717.

Thousands of enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic on Liverpool-registered ships in the 18th Century transatlantic slave trade.

Written evidence shows there was also a rising population of black residents at the time.

Liverpool and the slave trade

Much of the city's 18th Century wealth came from the slave trade

In 1700, Liverpool was a fishing port with a population of 5,000 people but by 1800, there were 78,000 residents, with thousands finding work due to the slave trade.

During the 18th Century, Liverpool made about £300,000 a year from the slave trade - the equivalent of the total generated by the rest of Britain's slave trading ports put together.

In the 1780s, Liverpool-based vessels carried more than 300,000 Africans into slavery.

By 1795, Liverpool controlled more than 60% of the British - and more than 40% of the European - slave trade.

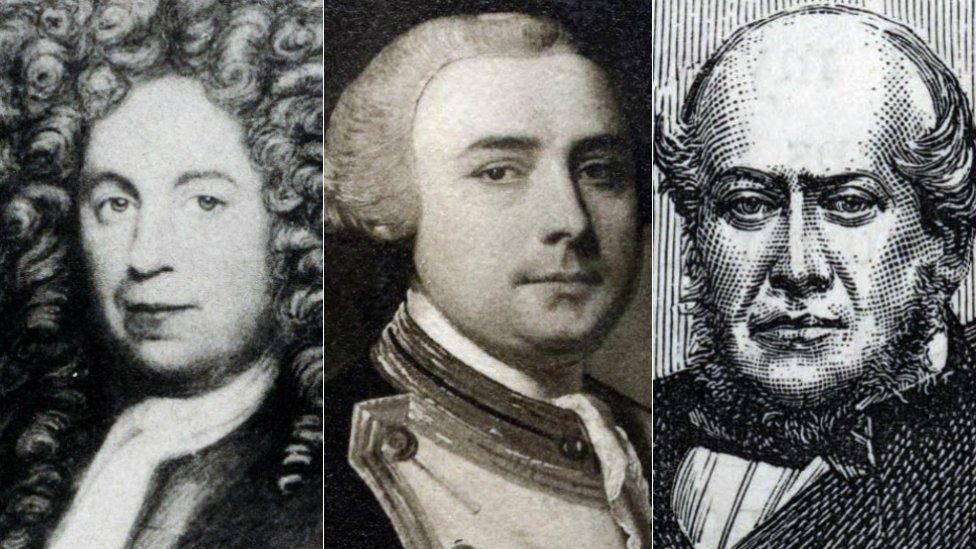

Nearly all the main merchants and citizens of Liverpool, including many of the mayors, were involved.

Source: BBC Bitesize

The stone, which marks the anniversary of Abell's funeral and coincides with Black History Month, was unveiled by Councillor Anna Rothery, who became Liverpool's first black lord mayor last year.

She said: "As a city we are facing up to the grim injustices of our past and, by setting them in their context, we are a better place."

Hundreds of people joined a Black Lives Matter protest in Liverpool this summer

More than 12.5m Africans were traded as slaves between 1515 and the mid-19th Century.

Some two million of the enslaved men, women and children died en route to the Americas.

Rector of Liverpool, Revd Canon Dr Crispin Pailing, said: "We cannot hide from our past, and there is no institution from this era of our history which is free from the taint of this horrific trade.

"We cannot give justice to Abell and other enslaved Africans, but we can give them the dignity of naming them when we can, and we can give them status within the history of our city."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Laurence Westgaph, who is historian-in-residence at National Museums Liverpool, said: "This gesture by St Nicholas Church records in stone the presence of black people in this town for more than 300 years and at a time when Liverpool's population was less than 10,000 people."

Following Black Lives Matter demonstrations in the summer, the city's council launched a project to ensure streets named after affluent slavers were given special plaques to explain their links to the trade.

The city also launched its own Race Equality Taskforce.

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published15 January 2020

- Published13 June 2020

- Published11 August 2020

- Published24 August 2020

- Published11 August 2020

- Published31 May 2015