St Ann's riot: The changing face of race relations, 60 years on

- Published

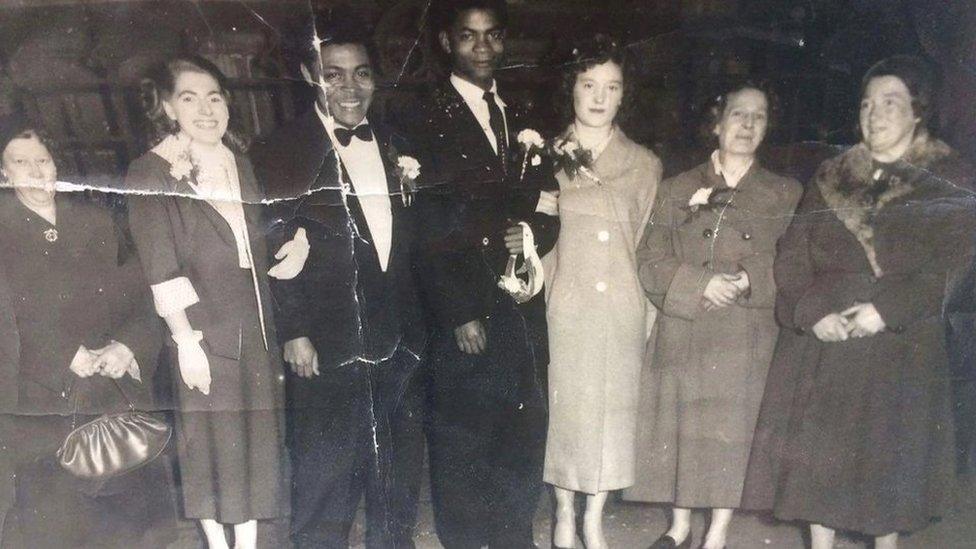

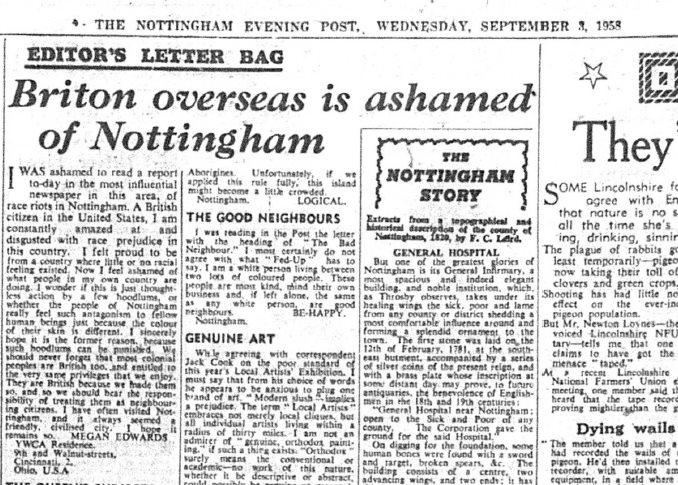

A mixed-race St Ann's couple marrying in 1957, a year before racial tensions exploded into violence

Sixty years ago, hundreds of people clashed on the streets of the Nottingham neighbourhood St Ann's, divided along lines of black and white. The BBC examines how the city united in the decades after the riot.

At first, 23 August 1958 felt like any other summery Saturday.

Families were gathering, parties were in full swing, young couples clutched hands as they walked the streets and groups of friends were enjoying themselves in local pubs.

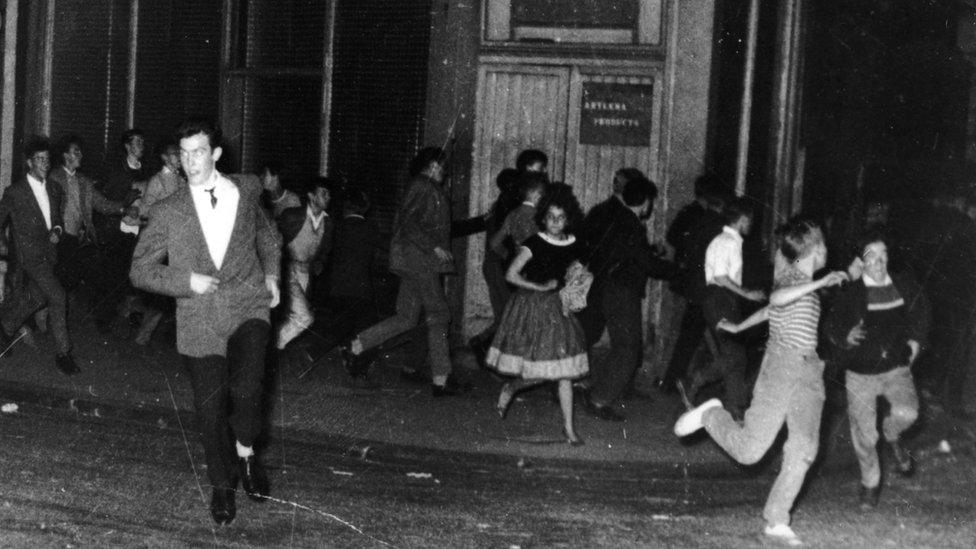

But in St Ann's, the easy weekend atmosphere soon soured, and for months afterwards local communities were picking through the wreckage of what was described at the time as "one of Britain's most bitter and ugly black-versus-white battles".

Sandra Russell had been coming home from a cinema trip - a treat for her recent 15th birthday - and as she walked through gangs of young men, she sensed the danger.

"There was a lot of young people - young black lads with knives, sticks, machetes, and the Teddy Boys had what they used to call cut-throat razors," she said.

"The atmosphere was really, really frightening. You knew something was going to happen, and you just didn't want to be there."

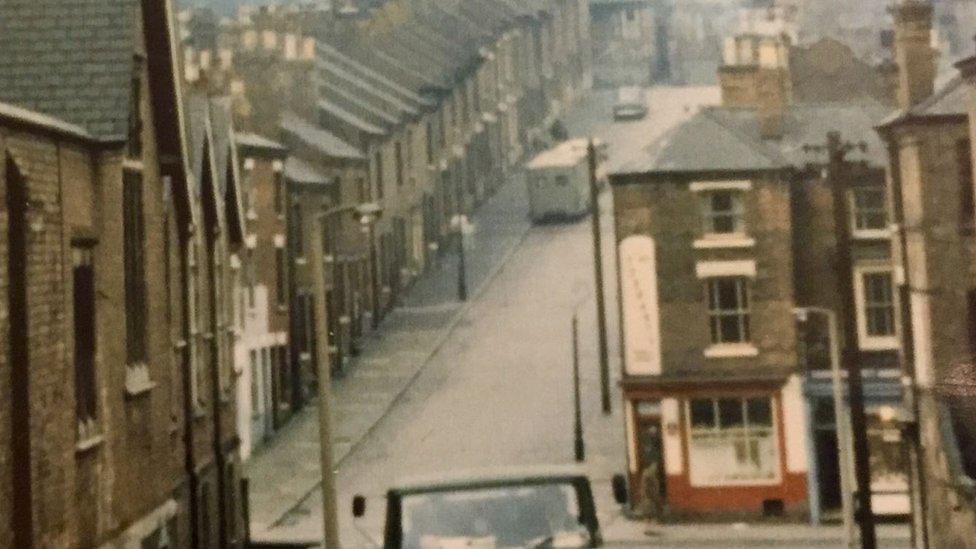

St Ann's was known for its tough living conditions but tight community spirit

In the aftermath of World War Two, Britain had called out for manpower to help rebuild a cracked and exhausted country.

The response of Empire is embodied by the Windrush, a ship that brought about 500 Caribbean passengers to London in 1948 and gave its name to a generation of Caribbean immigrants.

Commonwealth immigration rose from 3,000 people a year in 1953 to 46,800 in 1956, with communities settling in cities across the UK.

While the rescue call was widely welcomed, tensions between black and white would eventually boil over.

Ms Russell, whose mixed-race family had been in the UK for decades before Windrush, said the arrival of "vast numbers" of people from Commonwealth countries fed into post-war concerns.

"I think the resentment started maybe because of the war and the shortages that people had to experience, and when the war was finished they thought that things would get back to normal pretty quickly, which they did not," she said.

"My family, as far as I can remember, we never really felt any prejudice. There was the odd person, but because of my grandfather and my grandmother being here for so long, and because my mother was born here, we almost blended into the community."

Lisa McKenzie, a sociology lecturer at Middlesex University London, moved to St Ann's from Sutton-in-Ashfield in Nottinghamshire aged 18, and lived in the area for 25 years.

An expert on class and culture, she said the economic hardships harboured suspicion and hardened attitudes towards the Windrush arrivals, which, mixed with the "overt racism" of the times and "male competition" for female affection, fed resentments that eventually exploded into violence.

"There were thousands of people living cheek by jowl, very close to each other, often in very unsanitary conditions, and I think that played a massive part," she said.

"Everyone was struggling, whether they had just come from the West Indies or had been there for generations."

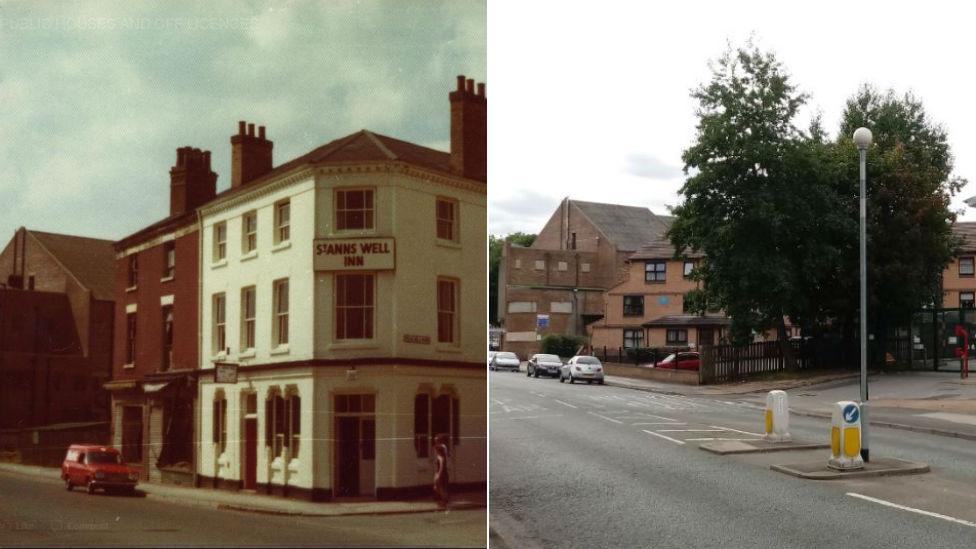

Some witnesses said the fighting started at the St Ann's Well Inn - the pub was later torn down as part of a redevelopment scheme

Exactly what caused the tensions in St Ann's to spill over into violence is unclear.

Some accounts cited a mixed-race couple being turned away from a pub on St Ann's Well Road as a trigger, while other accounts feature a staged fight spiralling out of control.

It ended in a scene described by the Nottingham Evening Post as "a slaughterhouse", with dozens of men and women injured and one man requiring 37 stitches to a throat wound.

The newspaper said more than 1,000 people were crowded in the area by the time police arrived.

Ms Russell said what started as "bravado" between young men leaving the local pubs worsened as the night went on.

"We came out of the cinema after the last showing... nothing had started off at that time, they were just congregating, and there was a lot of bantering back and forth from the Teddy lads and the black lads," she said.

"[Then] they just ran amok - it was like a gang war, they just laid into each other."

After the riot, Nottingham found itself at the centre of an international issue.

Government officials from Caribbean countries held urgent discussions with the Conservative administration in Westminster, as nations around the world looked at the UK's efforts to integrate immigrant communities.

The accounts of the race riot reached audiences in the USA, South Africa and further afield.

When similar riots broke out in the Notting Hill area of London a week later, the spotlight on Britain only intensified.

Catherine Ross moved from St Kitts to Nottingham aged seven in late 1958, and remembers the fears of her parents that they would be targeted.

"[Our] parents were telling us to be careful where we were going and be safe in what we did," she said.

Notting Hill in west London was the centre of similar disturbances soon after the St Ann's riot

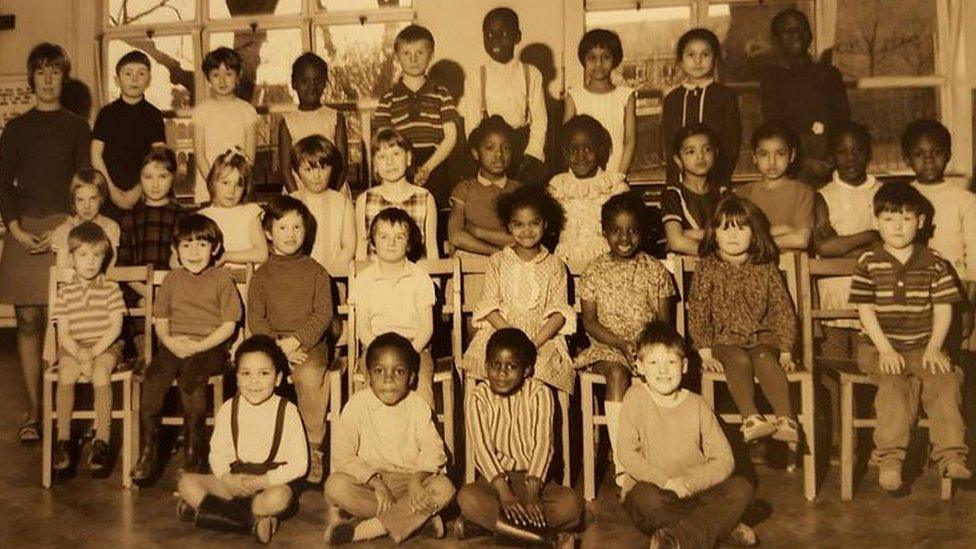

However, Dr McKenzie says the working-class communities that made up St Ann's soon saw what they had in common and put down roots that last to this day.

"After the riots there was a will from everybody that it wasn't who they were, and they didn't want it to happen again," she said.

"Once they started to live amongst each other, they realised they were very similar - it's the only place that put the racial differences to one side and focused on the class difference.

"There may have been fear of a mixed-race relationship, but when the babies were born families rallied round.

"That was my experience, and that's why I think St Ann's is such a special place.

"My son grew up as a mixed-race boy with a white mum and a black dad, and he never experienced racism."

Shebeen, a play written by Mufaro Makubika, was commissioned by Nottingham Playhouse to mark the anniversary

Ten years after the riots in Notting Hill and Nottingham, the landmark Race Relations Act 1968, external made it illegal to refuse housing, employment or public services to people on the grounds of ethnicity or nationality.

Six decades later, while the streets of St Ann's are more peaceful - not to mention redrawn after decades of slum clearances - the memory of the riot remains.

Nottingham Playhouse recently hosted the play Shebeen, which was set during the time of the riot, and efforts have been made to preserve the stories from 1958 for younger generations.

Ms Ross, who founded the Nottingham-based National Caribbean Heritage Museum, said the St Ann's disturbance needed to be commemorated.

"I think it's a bit of history they [some people] don't want to remember, but if you don't have the bad with the good you don't understand why people got upset," she said.

Ten years after the troubles, St Ann's was more multicultural than ever, as this local school photo shows

As for race relations today, Ms Ross cited recent racial tensions stemming from Brexit, austerity and the Windrush scandal as reasons for communities to continue to work together, but pointed to the progress made.

"The legacy [of the riot] as far as I am concerned are that we are now visible not just in factories and manual jobs, but in white-collar jobs and professional posts - we now have a variety of businesses visible on the high street and not just in areas where black people reside in numbers, and we welcome all people.

"We now educate, advise and manage white people - something they said could never be tolerated in the 50s and 60s."

For Dr McKenzie, the community of St Ann's has repaired itself after the riot in a way other areas have failed.

"In London it's still the same today - it's big enough for communities to almost segregate themselves, whereas in Nottingham you have to live with people, you've got to get on," she said.

"What was different about St Ann's was the way the community became stabilised and moved on.

"There's no such thing as a black or white family - everyone is very integrated, much more than in any community I've ever known."

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published9 May 2018

- Published28 August 2016

- Published22 August 2015