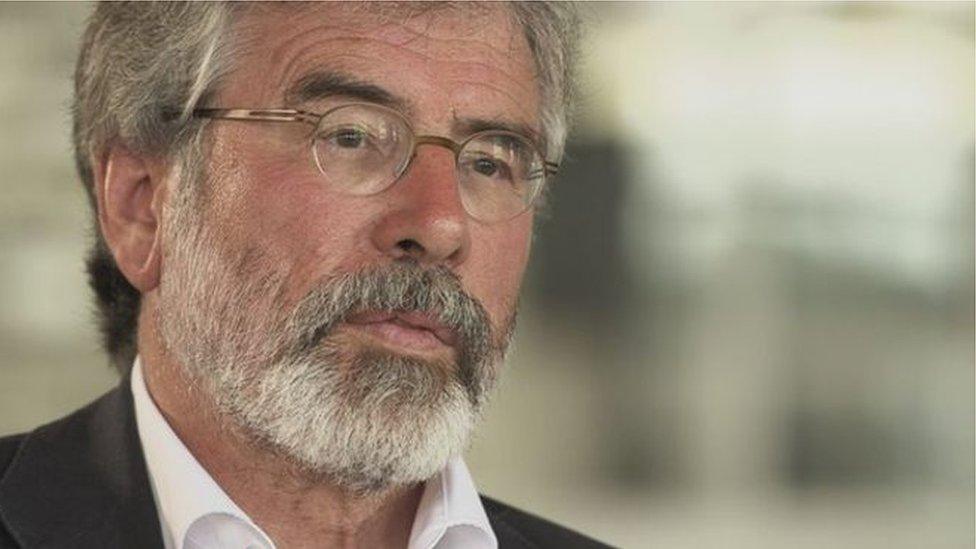

Gerry Adams: Profile of outgoing SF leader

- Published

Gerry Adams played a key role in leading republicans away from an armed campaign towards democratic republicanism

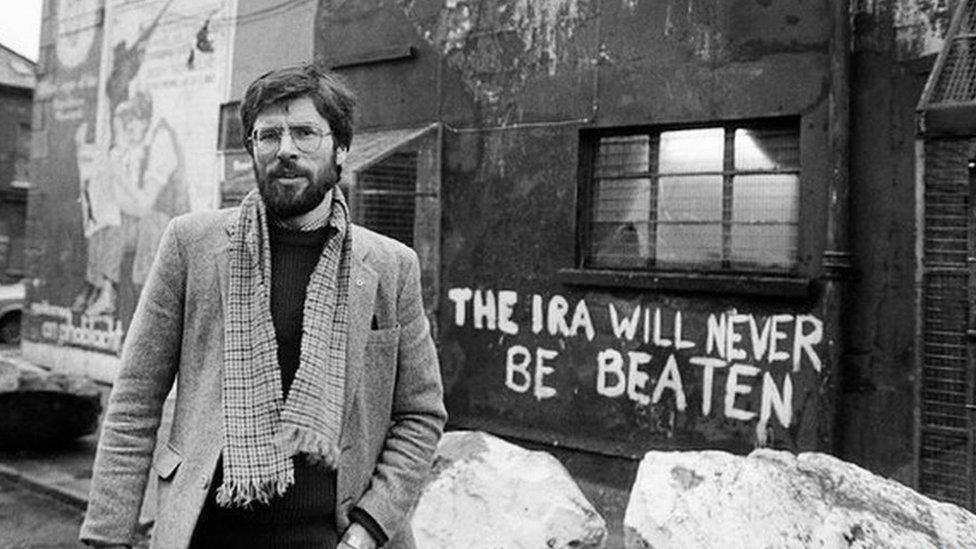

Gerry Adams says his first encounter with street politics came in west Belfast in 1964.

Police moved to remove a tricolour flag from the window of a republican election candidate, partly prompted by threats from the firebrand unionist Ian Paisley who had warned he would act if the authorities remained idle.

Adams said he took no part in the following days' riots but said that the impact was to encourage him to become "politically curious".

Four decades later, he and Ian Paisley, two implacable opponents, drew gasps when they were pictured sitting beside each other, their respective parties having signed up to power sharing.

Worshipped by supporters, regarded as a real-life bogey-man by opponents, as a leader of Irish republicanism Gerry Adams was always controversial.

That stems not from his position as leader of Sinn Féin, but from the role he is widely believed to have played within the IRA.

The allegation that he was at the very top of the terrorist organisation has been made repeatedly by journalists, political adversaries and former comrades, some of whom became informers.

Gerry Adams has consistently denied that he was ever a member of the IRA

While not disassociating himself from the IRA, Adams has always denied membership. The only thing he ever admitted shooting was a rabbit during a hunting trip.

The young Adams grew up in a west Belfast family steeped in republicanism; his father and two uncles were active in the IRA in the 1940s.

Adams wrote that his mother's family, the Hannaways, "were always republicans, members of each generation found themselves crossing the tracks of the preceding one".

Gerry Adams went to a primary school close to the family base in the Falls district, then attended St Mary's Christian Brothers Grammar School.

Violence spills onto streets

While at St Mary's, he joined Sinn Féin. A former teacher remembers him as "quiet, thoughtful - you would have hardly known he was in the class."

Leaving school with a handful of qualifications, Adams worked as a barman in the city centre, reportedly joining the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association's campaign in 1967. Its attempts to mount street protests were met by an increasingly harsh response from Stormont's unionist government.

A community worker and author wrote that, by August 1969, having initially become involved in agitation for better housing, Adams was "in a leadership position in Ballymurphy" and was involved in "organisational work" in the Falls, Ardoyne and Andersonstown areas of Belfast.

Gerry Adams pictured with IRA man Brendan Hughes in the Maze prison in 1983

Following a series of contentious Orange Order parades and civil rights demonstrations, violence again spilled on to the streets in the summer of 1969. Westminster deployed troops.

After a split within republicanism, the "Provisionals" eventually emerged as the more militant, bigger and more heavily-armed wing of the IRA.

The left-wing "Officials" had adopted a more cautious approach, unpopular with nationalists who saw themselves as under attack. Adams had close links to both camps but ultimately sided with the more radical Provisional leadership.

Within a short period, soldiers at first greeted as protectors in Catholic areas, were in open clashes following a series of weapons swoops.

In August 1971, a desperate Stormont administration secured London's support for the introduction of internment.

Internment without trial for those suspected of being involved in violence was introduced by Prime Minister Brian Faulkner.

Adams was interned on a prison ship moored in Belfast Lough, but was released the following year to arrange secret talks between the IRA and the British government.

An IRA group, which included Martin McGuinness, was subsequently flown to London.

Aged 23 at the time, Adams was said to have observed debate and to have remained largely silent during negotiations. The meeting revealed a chasm between what the IRA wanted and what the government was prepared to concede. In the limbo following the encounter, a ceasefire quickly broke down.

In 1973, Adams was again interned, his compound within Long Kesh, Cage 11, becoming known among other internees as the centre for debate.

Hunger striker Bobby Sands pictured with Gerry Adams among a group of prisoners in the Maze

While there, Adams penned several articles for An Phoblacht/Republican News. Under his 'Brownie' pseudonym he called for more political involvement. He was attempting to overturn his only convictions, an 18-month sentence for two escape attempts, during this period.

Upon release from Long Kesh, Adams gradually assumed a more public political profile, in 1978 becoming Sinn Féin vice president.

In the constant foreground was the continuing violence as the IRA, British army and loyalist paramilitaries engaged in a conflict that claimed thousands of lives. Indeed, the actions of the IRA in the mid to late 1970s would repeatedly dog Adams' political career.

By the late 1970s, the situation in the jail was becoming increasingly volatile. The authorities had ended what republicans called "political status" for prisoners. They mounted a series of protests against what they saw as the British government's attempt to "criminalise" their campaign.

That culminated in 1981 with a number of inmates embarking on hunger strikes. Standing hunger strikers in elections on both sides of the border propelled Sinn Féin into mainstream political activity.

Bobby Sands won a parliamentary by-election in Fermanagh and South Tyrone. Kieran Doherty was elected to the Dáil (Irish Parliament).

Adams knew both of the men, who were among the ten who died on hunger strike.

Former IRA prisoner Richard O'Rawe later claimed that Adams and other republican leaders outside the prison had rejected a deal which could have ended the strike and saved six of the hunger strikers' lives. His claims have been strongly disputed by Sinn Féin.

Nevertheless, from the point of the hunger strikes, with Adams increasingly in control, Sinn Féin became a steadily growing electoral force.

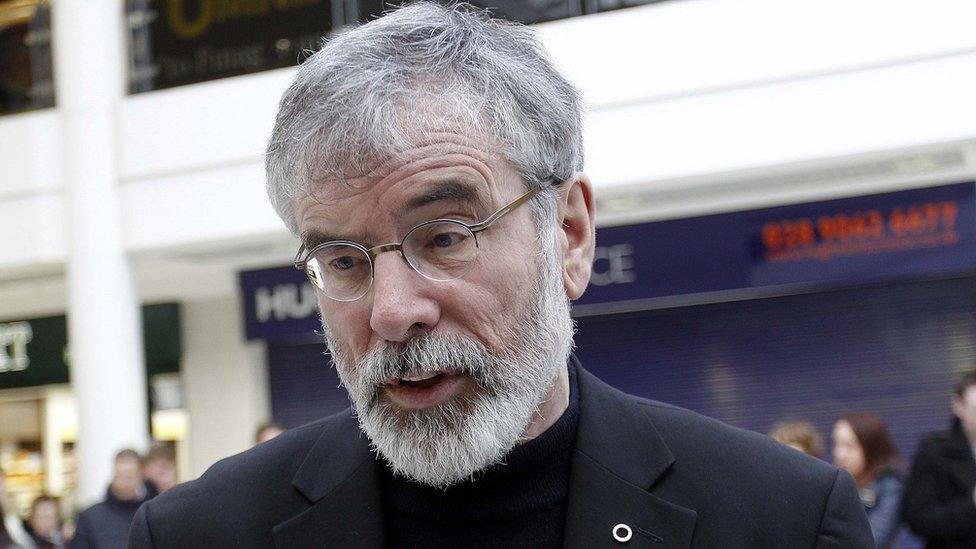

In 1983, Adams was elected as an abstentionist MP for West Belfast - that meant not taking up his seat in Westminster. That same year, he became party president finally ousting more conservative and traditional opponents.

The position was not without personal risk. In March 1984, he was shot several times in an assassination bid by the loyalist paramilitary Ulster Defence Association in Belfast.

Gerry Adams outraged unionists when he carried the coffin of IRA bomber Thomas Begley in 1993

Over years, he attended the funerals of scores of IRA members, many of them known to him personally. There is an early image of him wearing thick-rimmed glasses and a black beret at an IRA funeral.

His attendance at such funerals, including carrying the coffin of individuals like Thomas Begley, the Shankill bomber, outraged unionism. Equally, it was exactly what republicans would have expected of their leadership.

Unable to check republican electoral successes, for a six-year period from 1988, the British government imposed restrictions on broadcasters which meant that the voices of Adams and other Sinn Féin members had to be dubbed by an actor. Mirrored by the Irish government, if anything, the ban increased his public profile.

Always cautious, never moving without the backing of the core of the IRA leadership, some republicans say Adams would both encourage and stymie debate depending on whatever suited his purpose at any particular moment.

"Ruthless" and "calculating" are two words used to describe him while others will just as easily use words like "warm" and "charismatic".

Adams engaged in secret talks with the then leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party leader, John Hume

Even political opponents and members of the security establishment have expressed grudging admiration for his ability to move republicanism without provoking internal division.

As early as 1986, Adams engaged in secret talks with the then leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party leader, John Hume, a contact initiated via a Redemptorist priest at Clonard Monastery in Belfast.

In May 2007, the DUP and Sinn Féin agreed to share power

Through a clandestine back channel, republicans also began contacts with the British.

Killings continued with deadly regularity, the names of Enniskillen, Loughgall, Milltown, Warrington, Shankill just some of those inscribed on a litany of carnage.

In 1991, the IRA fired mortars at Downing Street where John Major's Cabinet was meeting.

In 1994, then US President Bill Clinton, taking a personal interest in the peace process, issued a visa waiver to allow Adams to speak at a function in America. In the summer of that year, the IRA declared a ceasefire.

Torturous start-stop negotiations followed for more than two years. President Clinton says in his autobiography that Adams called him to tell him the IRA ceasefire was over just before a huge IRA bomb exploded in Manchester.

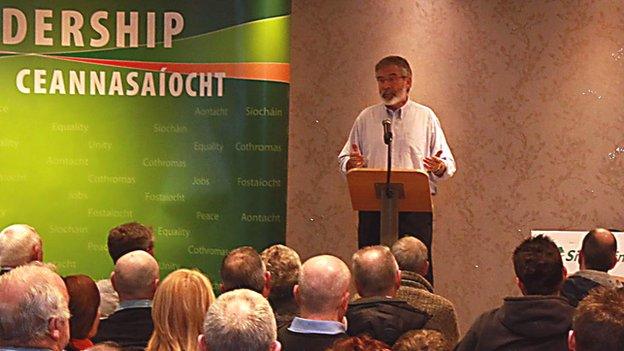

Gerry Adams has led Sinn Féin, Northern Ireland second biggest political party, for more than 30 years

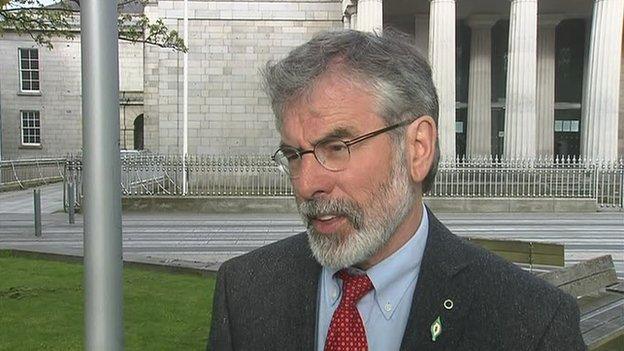

It took two years of tentative negotiations and more killings before the IRA announced another ceasefire and this in turn led to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

It included provisions for prisoner release and paramilitary decommissioning. A separate review saw the name of the Royal Ulster Constabulary replaced by that of the Police Service of Northern Ireland., external

Adams was able to portray this as a considerable republican victory.

He has denied involvement in specific atrocities including the bombings on Bloody Friday and at the La Mon Hotel as well as the abduction and murder of Belfast mother-of-ten Jean McConville.

In the latter case, specific allegations were made by one-time fellow internee and close confidante, Brendan Hughes.

The mother of ten's body was discovered on a County Louth beach after a storm in 2003.

Adams had been successful in a bid to represent the Louth constituency in the Irish parliament.

In 2014, during an election campaign, his arrest and questioning over a four-day period about the McConville murder provoked republican ire. He was a questioned for four days, before being released. The Public Prosecution Service later confirmed that he would not face charges over the murder.

Accusations about Gerry Adams' IRA past did nothing to hold back Sinn Féin's inexorable political rise, with the party taking ministerial posts at Stormont and later, in 2007, with the party eclipsing the SDLP, Martin McGuinness became deputy first minister.

There were key moments when Adams was caught off guard making comments that riled and offended the unionist community.

In 2014, he was recorded by the Impartial Reporter at a meeting in Enniskillen saying, "The point is to break these bastards". He later apologised and said he was referring to "bigots" and not all unionists.

He also said he partly regretted using a "Trojan horse" analogy when referring to Sinn Féin's equality strategy and that this was a political gaffe.

But the DUP said that a full transcript showed that Mr Adams was referring to the DUP when he used the offending phrase.

The party's Arlene Foster said: "I'm glad the Impartial Reporter has a recording of Gerry Adams' mask slipping moment.

When McGuinness' ten-year tenure in the position ended with his resignation in January 2017, it was widely believed that republican patience with what they perceived as unionist intransigence at Stormont had reached breaking point.

Gerry Adams with the party's leader at Stormont, Michelle O'Neill, in June

Behind the decision effectively collapsing the Assembly was Gerry Adams and a tightly-knit, small group of trusted advisors.

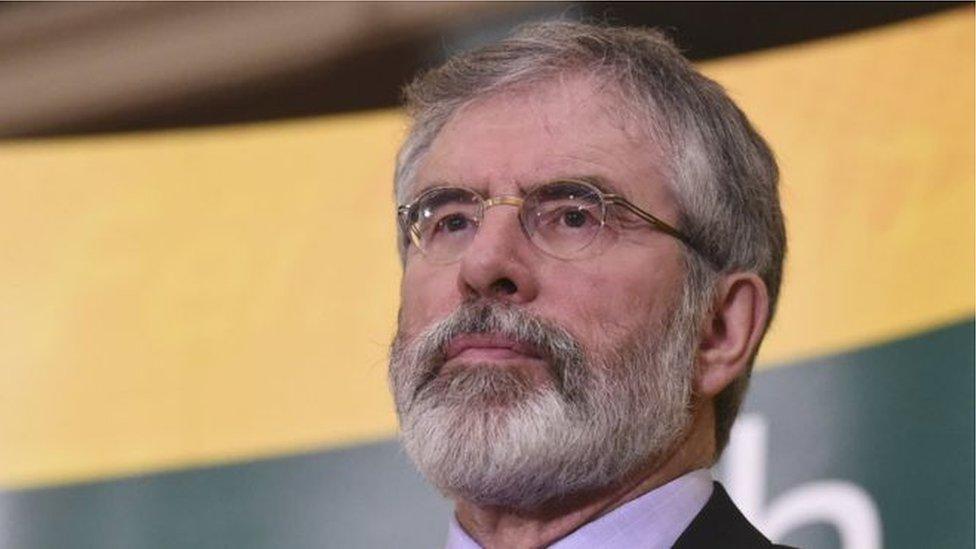

In many ways, Adams deserves the title of "last man standing" in terms of both Irish and British politics.

In more than half a century, he saw off all manner of political and personal threats.

When he joined Sinn Féin he says he found it "weak and disorganised".

He steps down as leader leaving it the dominant nationalist voice in the north and the third largest party in the Republic of Ireland where it is now in contention for ministerial position.

- Published20 November 2017

- Published2 December 2017

- Published29 September 2015

- Published25 November 2014

- Published9 August 2011

- Published4 May 2014