NI 100: 'Londonderry's forgotten week of bloodshed' in 1920

- Published

When the Government of Ireland Act was granted Royal Assent in December 1920, it came at the end of a troubled year in Londonderry.

Six months earlier in the city, a single week of violence had claimed 20 lives.

It was the "first upsurge of sectarianism", according to Ulster University historian Dr Adrian Grant.

That week in June, he said, was "a hugely significant but largely forgotten time".

"The sectarian powder keg that had been sitting there for some eight or nine years had been well and truly lit," Dr Grant told BBC News NI.

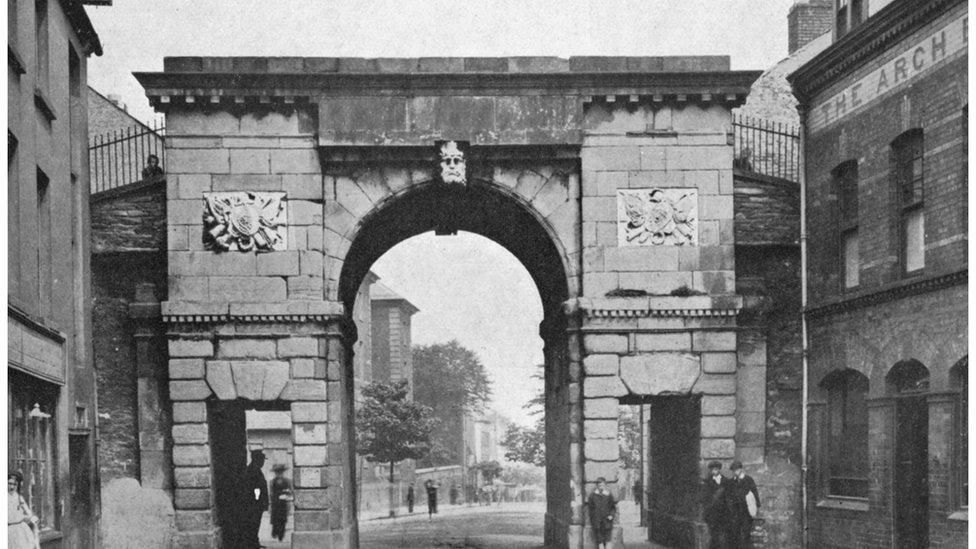

Much of the violence occurred in the Bishop Street area

The city's electorate had returned a Sinn Féin MP in the 1918 Westminster elections.

In January 1920, it elected a majority nationalist council which, in turn, returned a nationalist mayor.

Flag flying from the city's Guildhall was prohibited and the new mayor, Hugh C O'Doherty, would not attend any events where a toast to the Crown would be made.

The council also moved to remove the Freeman of Derry title from Lord French, who had served as commander-in-chief of the Home Forces during the time of the 1916 Easter Rising.

Dr Grant said unionists felt their British identity was under threat.

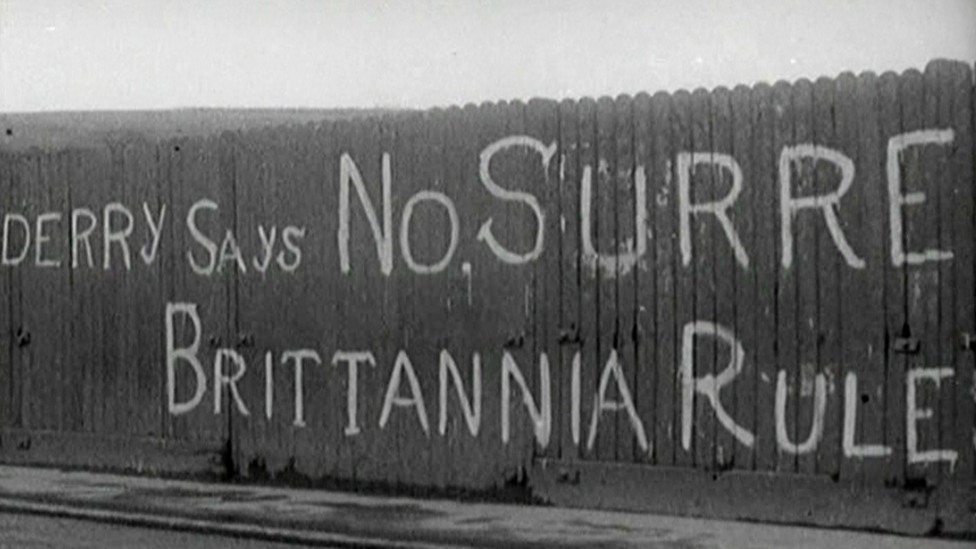

Graffiti from the time reflects the unionist sentiment

This was a city synonymous with unionism's siege era cry of "No Surrender".

There was "almost an inevitability that there would be bloodshed", Dr Grant said.

Trouble between nationalists and unionists broke out sporadically from early 1920, gaining momentum by the middle of the year.

Dr Grant added: "Each weekend from the spring onwards there were skirmishes in Derry, small scale riots."

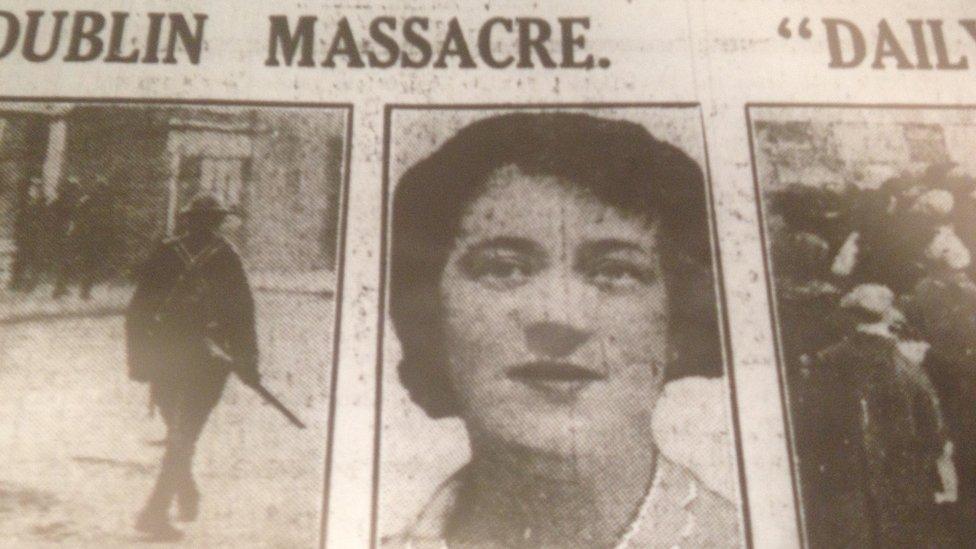

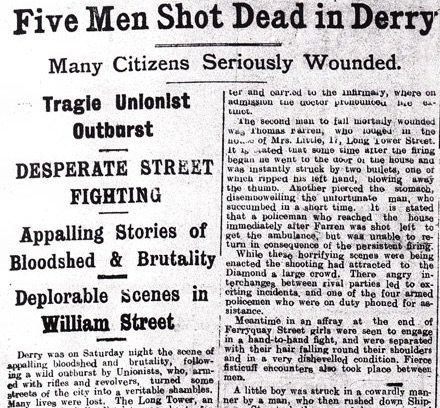

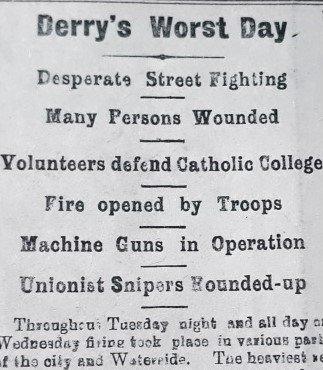

How the Derry Journal reported events of 19 June 1920

Londonderry's 'forgotten week of bloodshed' in 1920

On the night of 19 June, Dr Grant said "things took a completely different, horrific turn".

That was when "a group of unionists, probably World War I veterans, most likely UVF members, started to fire into a crowd in the Diamond".

Four men were killed. A fifth would die two days later of his wounds.

Among them was Edwin Price, staying in the city having returned from America, shot at the door of the Diamond Hotel and Thomas McLaughlin, who lay dying amid ongoing gunfire after being shot in the throat.

Nationalists, armed with revolvers, returned the unionist rifle fire and the violence intensified in the days thereafter.

Dorset Regiment soldiers on Derry's streets in 1920

Unionist snipers took up positions across the city.

The IRA mobilised, setting up headquarters in St Columb's College.

They were joined by a number of volunteers, some who were themselves veterans of the British Army in World War I.

Remembering the events of June 1920

For Ivor Doherty, the events of 1920 are more than a vague, near-forgotten tale of long ago.

As a child, his mother would often tell him of his grandfather Matthew Doherty.

A nationalist who had first joined the British Army in 1890, he signed up again in 1914, re-enlisting, as he saw it, to advance the Home Rule cause.

Matthew Doherty had joined the British Army in the late 19th century

By June 1920, Matthew, who had been officer commanding of Derry's third battalion of the Irish National Volunteers, was back home in Derry. When the gunfire came that June day, he couldn't get home from his work on the city's docks.

"My mother told me he never came home that day, nor for the next seven days, exactly the length of time Derry's civil war lasted," Ivor said.

He had taken up arms to defend his community, Ivor said, first protecting businesses in the city centre, then joining those at St Columb's.

Thirteen of those killed died in the city's Bishop Street/Long Tower area, where Ivor lives.

Often he sees descendants of some of those killed.

Ivor Doherty would like those killed to be remembered with a permanent memorial

Earlier this year an exhibition, compiled by a number of community groups, including Áras Cholmcille, external and the Museum of Free Derry, external, went online.

Ivor was integral to the research, keen that the personal stories of those who lost their lives would not be forgotten.

Now it's his hope the events and people of 1920 will be honoured with a more permanent memorial in Derry.

At times, nationalists and unionists fought openly on the city's streets. Men were ambushed as they made their way to work.

"People were being shot dead in the street, mainly innocents, mainly bystanders," Dr Grant said.

"This wasn't guerrilla tactics or sporadic shootings, it was open warfare, full scale war.

"Some were caught in the crossfire, some were specifically targeted".

The Derry Journal reported an intensifying situation as the week went on

Seven summer days would claim the lives of 15 Catholics and five Protestants as gunfire, coming from both sides of Derry's sectarian divide, ripped through the city.

On 21 June, Howard McKay, the son of the governor of the Apprentice Boys was blind folded and shot on his way home.

That same day, James Dobbin was beaten and shot, his body dumped in the River Foyle.

An inquest into his killing recorded: "Dobbin remained struggling for a significant period in the water, hanging on to a boat, while the 'nationalists', at revolver point, kept at bay anyone who attempted to go to his assistance."

Two women were among the week's dead.

Margaret Mills was killed on 23 June. The following day, Elizabeth Moore died from a gunshot wound to the head as she answered what she thought was a knock on her front door.

The youngest victim was 10-year-old George Caldwell, shot as he peered from a window of the Nazareth House care home on 24 June.

The violence came to an end when the military were ordered in and martial law imposed.

At an inquest into the boy's death, the coroner said that if the government sent in the Dorset Regiment sooner "there would have been fewer deaths and less property destroyed".

Dr Grant said violence in Derry in 1920 was "almost inevitable"

On the ground there too was a desire to end the bloodshed, Dr Grant said.

"There was a sort of conciliation," he said.

"Older IRA commanders who had seen violence in the 19th century knew what could happen if things spiralled too far.

"There was work going on behind the scenes, both unionist and nationalists coming together to try and protect communities and businesses and to make sure it did not happen again in the city."

On 26 June, as the violence abated, the Londonderry Sentinel's editorial read: "Deeds have been done and outrages perpetrated which should bring the blush of shame to the faces of decent people.

"Men who should be respectable have lost their heads and become assassins and footpads."

It said of the city's unionist population that the "struggle was not of their seeking, but was forced upon them".

"Their desire as enlightened Derrymen is for peace. But when attacked they can scarcely be expected not to make the best defence in their power."

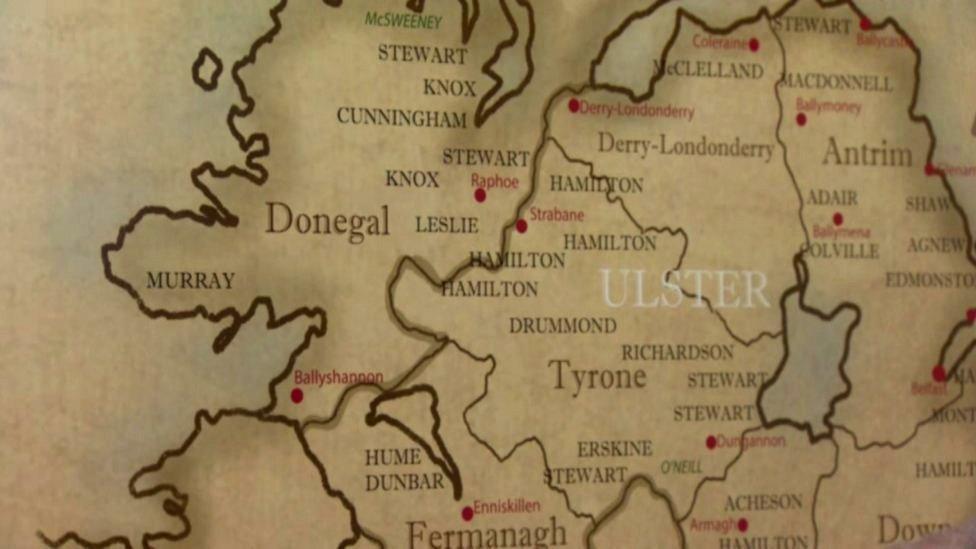

Both nationalists and unionists did not want the connection between Derry and Donegal broken by partition

Within weeks, a calm had been all but restored.

"It went relatively silent in the north west after the events of June," Dr Grant said.

In the north west, attentions turned to how the Government of Ireland Act, and the subsequent Boundary Commission, would treat Derry and its natural hinterland of Donegal.

Unionists and nationalist may have wanted different things politically, Dr Grant said, but neither wanted the "connection between the two areas broken".

When Ireland was partitioned in 1921, Donegal did not form part of the new state of Northern Ireland.

Update 25 February 2021: This story was amended.

Related topics

- Published23 December 2020

- Published21 December 2020

- Published21 November 2020