Ken Clarke hails deal to overhaul European Court of Human Rights

- Published

- comments

Justice Secretary Ken Clarke: "Get rid of all the trivial cases. Get rid of all the years of delay"

Justice Secretary Ken Clarke said an agreement reached at a conference in Brighton will make "a big difference" to the European Court of Human Rights.

The 47 member countries have been discussing UK plans to curb its powers.

Court president Sir Nicolas Bratza said the Brighton declaration would "not change the way we do our jobs".

But Mr Clarke said it would reduce the "appalling backlog" of cases and "scandalous delays" that currently dog the court.

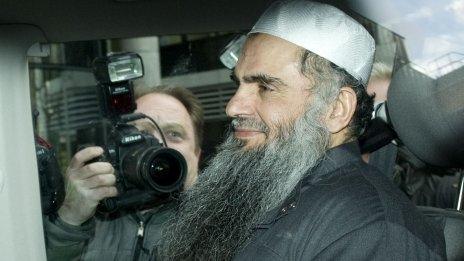

The UK has criticised some judgements, including giving prisoners the vote and blocking the deportation of Abu Qatada.

At the end of last year, judges in Strasbourg faced a backlog of nearly 152,000 cases, of which an estimated 90,000 will end up being categorised as "inadmissible".

Opening the Brighton meeting, Mr Clarke said "huge progress" had been made in tackling the number of inadmissible cases, but the court was still receiving more admissible cases than it could handle in "a timely manner" - some 3,000 a year, compared with a manageable workload of 2,000.

He said some of those "stuck waiting in that queue" would be serious cases that "should not wait years before they are determined".

'Uncomfortable'

Sir Nicolas has suggested that reform was already under way and the backlog was being tackled.

But at a press conference following the agreement of the declaration, Mr Clarke said he did not take "so leisured" a view as the court president.

"I won't accuse him of complacency, but I'm a little less relaxed than Sir Nicolas about the progress that's been made before the Brighton Declaration, which I think will make a big difference," he said.

Sir Nicolas said he was "uncomfortable" with governments trying to "dictate" the court's operations.

"In order to fulfil its role the European court must not only be independent, it must also be seen to be independent," he added.

He said it was "not surprising that governments and indeed public opinion in different countries find some of the court's judgements difficult to accept".

"[But] it is... in the nature of the protection of fundamental rights and the rule of law that sometimes minority interests have to be secured against the view of the majority."

'Very trivial cases'

Mr Clarke said he understood Sir Nicolas's "defensiveness", but member states had a duty to make sure the court operated efficiently.

"Tackling the logistics of the court which are leading to delays... is not in my opinion threatening the independence of the court in the slightest."

The justice secretary went on: "We're making sure that we require the court to act more promptly on the sort of cases that this court should be dealing with.

"Stop being so slow in getting rid of some of the triviality, stop hearing some of the very trivial cases where there's no substantial damage... and just to give prompt decisions on those fewer cases which require a decision."

The UK had sought agreement on the principle of "subsidiarity" - to limit the court's ability to overrule cases already determined by national courts.

The other main principle demanded was to allow a "margin of appreciation" - giving national governments greater leeway in applying the judgements of the court.

Mr Clarke said earlier there could not be "an absolute rule" giving pre-eminence to national courts or parliaments, but it would not "very often happen" that a domestic decision would be overruled.

The UK government estimates this could happen within a couple of years.

'Underlying issue'

Thorbjorn Jagland, the secretary general of the Council of Europe, told the BBC earlier that individual member states - "where the convention has not been implemented fully" - were responsible for the court's problems.

Speaking alongside Mr Clarke later he said the declaration would make it easier for the court to "put aside" unsuitable applications.

But Dr Michael Pinto-Duschinsky, who recently resigned from his position on the commission considering a UK Bill of Rights, said that although some "generally useful words and goodwill" might come out of the conference, it would not resolve "the underlying issue, which is, where does the buck stop?"

"The document says quite clearly that that final authority rests with Strasbourg, so whatever cosmetic concessions are made will really not mean very much."

Critics of the UK's desire to reduce the court's workload say it risks damaging access to justice in some member countries, including Russia and Ukraine.

- Published23 April 2012

- Published5 February 2015

- Published19 April 2012

- Published19 April 2012

- Published5 February 2015

- Published29 March 2012

- Published25 January 2012