Are the rules which have stopped nuclear war broken?

- Published

"We are moving in a minefield, and we don't know from where the explosion will come."

A warning from former Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov delivered at this week's influential Carnegie International Nuclear Policy Conference in Washington DC.

Former US senator and long-time arms control activist Sam Nunn echoed the sentiment. "If the US, Russia and China don't work together," he argued, "it is going to be a nightmare for our children and grandchildren."

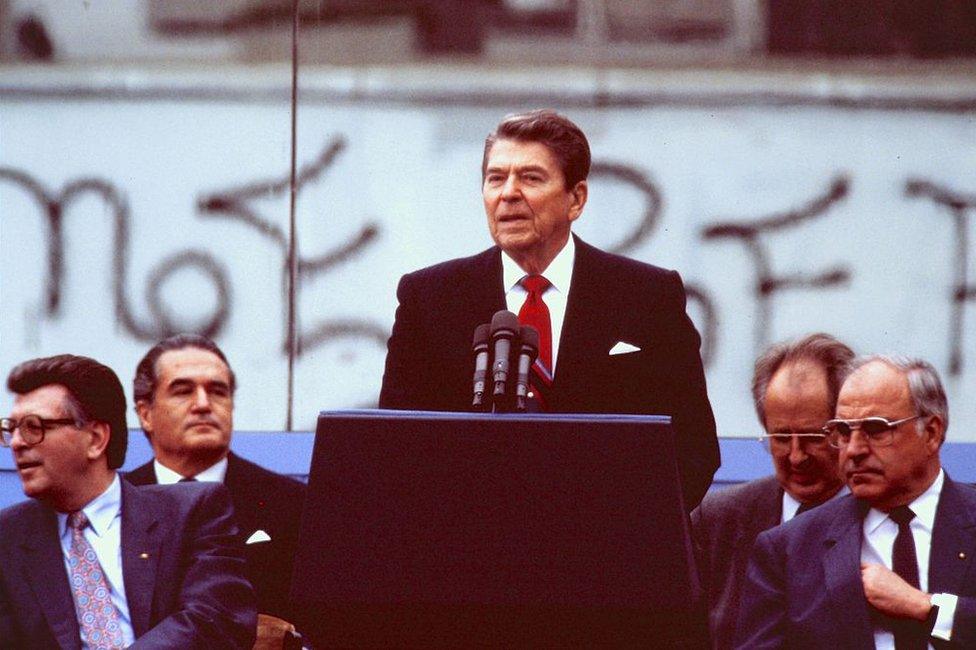

He urged the present leaders to emulate the approach taken by Presidents Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev towards the end of the Cold War, and to rally around the premise that nuclear war cannot be won, and must therefore never be considered.

Mr Reagan dreamed of missile-proof ballistic missile defences, but also came close to negotiating a comprehensive nuclear disarmament deal with his Russian counterpart Mr Gorbachev.

Ronald Reagan's call to Mikhail Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall in June 1987 was widely seen as helping to end the Cold War

His endeavours led to the Start Treaty, which scaled back the two nuclear superpowers' cache of weapons.

Today the future of that treaty's successor - the so-called "New Start agreement" - is in doubt. The intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) treaty has collapsed, after the US and then Russia suspended participation.

US President Donald Trump insists that Russia has broken the agreement for years, and has now deployed battalions of ground-launched cruise missiles that breach its terms.

Russian President Vladimir Putin denies this, but Nato colleagues have backed Washington.

Nonetheless, many US allies are unhappy with Mr Trump's whole approach to international affairs, as was apparent at the conference.

US President Donald Trump has clashed with European leaders including German Chancellor Angela Merkel

Germany's ambassador to the US, Emily Haber, pointed to the "erosion of the system of rules" which had previously regulated the international system.

She noted the extensive use of economic sanctions to punish a country's past behaviour rather than shape its future conduct, a reference perhaps to US sanctions against Russia in the wake of its 2015 seizure of Crimea.

This is a complex business.

Ms Haber did not simply condemn the Trump administration, despite obvious tensions between the US president and German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

She also cited a variety of provocations from Mr Putin, which she said have eroded trust and diplomatic process.

Since annexing Crimea in March 2015, Russia has built a fence along the Ukrainian-Crimean land border

Many conference speakers stressed that it was not simply that the old arms control edifice was crumbling; nor that wider tensions between the nuclear superpowers were growing.

It was not even just the challenges posed by a rising and more assertive China or growing rivalries between nuclear-armed India and Pakistan.

They fear something new and dangerous is looming.

Just as the old arms control order is collapsing, novel high-tech challenges are already here. Consider highly accurate conventional missiles flying at hypersonic speeds, cyber-weapons, the potential militarisation of space, the impact of artificial intelligence, and so on.

The whole warning system on which deterrence rests could be undermined.

As Mr Nunn put it: "In this new era, we are much more likely to have war by blunder or miscalculation - by interference from third parties - than from a deliberate premeditated attack."

This was not a conference to raise the spirits. Its message was profoundly depressing.

Andrea Thompson, US Under Secretary of State for Arms Control, warns that the new order needs new policy solutions

Could the INF treaty be resurrected, perhaps in a wider context to bring in China? Forget it.

Andrea Thompson, US Under Secretary of State for Arms Control, made it clear that China had indicated no interest in such a deal.

Can the New Start treaty - the cornerstone of US-Russia nuclear disarmament - be saved?

Time is short. It expires in early February 2021. And although presentations from senior US and Russian officials acknowledged its utility, there was little enthusiasm for any extension.

New Start should not be written off yet. But it may become a casualty of the wider hostile climate between Washington and Moscow.

Nor was there good news for the conference on another tenet of Mr Trump's diplomacy - the promised nuclear deal with North Korea.

After the failure of the most recent Trump-Kim summit, it is not clear where US policy towards North Korea is heading

At the Hanoi summit, Mr Trump went for a grand bargain with Pyongyang.

But his North Korean counterpart was only prepared to sacrifice a small part of his country's nuclear programme, demanding in return, a full-scale lifting of economic sanctions. Mr Trump chose to walk away.

Stephen Biegun, the US special representative for North Korea, was clear. The Trump administration's line has toughened - perhaps under the influence of National Security Adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

But for all Mr Biegun's efforts to paint the president's gambit as coherent and credible, there is no consensus on where US policy towards North Korea is heading, nor when, where - or even if - this diplomatic odd couple might meet next.

Something worrying is afoot.

As Ms Thompson noted, the rate of technological progress is not being matched by the rate of policy formulation. "How," she asked, can you elaborate "rules of responsible behaviour" in this climate?

Many shared her concern.

If treaties limiting old-style weapons are unravelling, how much harder will it be to agree measures to control new ones? Is the era of traditional arms control over?

There was a broad sense - from Russians, Europeans and many Americans alike - that a dialogue on strategic stability between Washington and Moscow is urgently needed.

That will not be easy given the ongoing Mueller probe into the Russian government's efforts to interfere in the 2016 US presidential election, or Mr Putin's actions in Syria and Ukraine.

At the height of the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union threatened each other with mutual destruction.

That produced a system of treaties and understandings, but it seems that old rule book has now been thrown out.

Old enmities are back, and could be more dangerous than ever, given the apparent lack of any mechanism or willingness to manage these expanding tensions.

- Published28 February 2019

- Published8 February 2019

- Published1 February 2019

- Published1 February 2019

- Published14 January 2019

- Published4 December 2018