Could Westgate deal a fatal blow to the ICC?

- Published

Somali Islamist group al-Shabab said it was behind the Westgate attack

Western nations backing Kenya's counter-terrorism efforts face a moral dilemma over whether to defer the International Criminal Court (ICC) trial of President Uhuru Kenyatta after last month's Islamist attack on the Westgate shopping centre, write BBC Africa's Solomon Mugera and Moses Rono.

The challenge is compounded by the tone coming from Nairobi that strongly suggests that Mr Kenyatta might not turn up for his trial at The Hague in November.

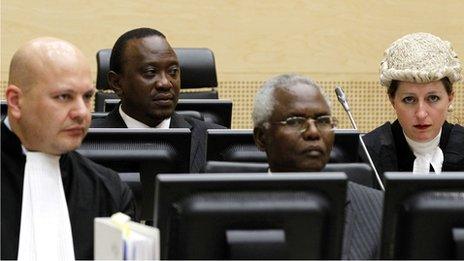

Since being indicted on charges, which he denies, of organising violence after the disputed 2007 elections, Mr Kenyatta has consistently said he would co-operate with the ICC.

But the reality of what having a president on trial abroad really means struck home when Islamist militants seized the Westgate mall in the Kenyan capital last month, leading to the deaths of at least 67 people.

Mr Kenyatta's deputy, William Ruto, was in The Hague in a related case at the time and he had to ask the court for special dispensation to adjourn the hearings and return home.

"Suppose Kenyatta was in The Hague attending his trial at the time the siege happened?" a source at the presidency wondered at the time.

Principle v realpolitik

Independent Horn of Africa analyst Abdullahi Boru views the situation as a conundrum pitting justice against security.

"The West faces a dilemma of principle versus realpolitik," he told the BBC.

"Do they insist on saying the court should go ahead with the cases, or capitulate to the demands of the African Union (AU) and Kenya?"

African leaders have asked the UN Security Council to postpone Mr Kenyatta's trial - they have long accused the ICC of unfairly targeting African leaders.

They further asked the Kenyan president and Mr Ruto not to show up for their respective trials until the UN hears the request for a deferral.

The UK and France have championed the ICC as a vital tool to help bring to justice those politicians who carry out atrocities in their quest for power and would be loath to undermine the court by agreeing to the AU demand.

The US supports that principle but has not signed up to the ICC for fear its own soldiers could be prosecuted.

During Kenya's election campaign earlier this year, the UK and the US warned that a Kenyatta victory would have "consequences" for the country.

In the event, he turned this around, successfully portraying it as neo-colonial meddling in Kenya's sovereign affairs and was elected president.

Even before Westgate, this put the West in a difficult position.

'No longer personal'

Alongside Ethiopia, Kenya is a key ally in counter-terrorism efforts in the region.

Nairobi hosts a significant number of African offices for major multilateral organisations, and the world headquarters for the United Nations Environmental Programme.

As the biggest, most developed city in East Africa, it is home to a large number of Western expatriates.

Kenya also has strong intelligence - and other - links with the US and Israel.

As al-Qaeda and its branch in neighbouring Somalia, al-Shabab, have stepped up attacks in the region, both US and Israeli targets in Kenya have been hit by al-Qaeda militants.

The UN Security Council is now expected to decide whether to defer the trial of Mr Kenyatta or let it continue - both options entail considerable risks.

George Kegoro, the executive director of the International Commission of Jurists-Kenya, told the BBC that extensive lobbying was going on, including a recent visit to Addis Ababa by the 15 Security Council members for consultations with AU officials.

In Kenya, the debate is raging.

Kenyan law scholar Makau Mutua criticised the AU resolution seeking a deferral of Mr Kenyatta's case.

"The message is we can kill; we can maim; we can commit genocide; we can rape our people with impunity and that no court can bring us to account for those crimes," he told Kenya's private NTV channel.

While the US-educated Kenyan president is generally known to be easy going and diplomatic, at the AU summit, he lashed out at the court, and the West, leading many to ask whether he would still attend his trial.

"The ICC has been reduced into a painfully farcical pantomime, a travesty that adds insult to the injury of victims," Mr Kenyatta said.

"It stopped being the home of justice the day it became the toy of declining imperial powers."

While campaigning for the March 2013 presidential vote, Mr Kenyatta called his trial at the ICC "a personal challenge".

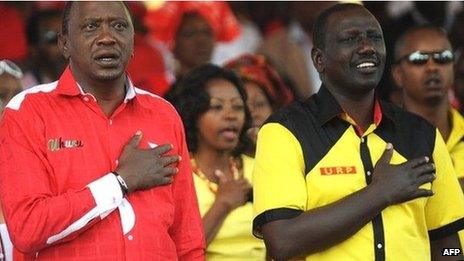

Uhuru Kenyatta (left) and William Ruto deny organising post-election violence

That now appears to have changed.

"Once that person is elected into office, there isn't anything personal about him," presidency spokesman Manoah Esipisu told the BBC's Focus on Africa programme.

He noted that the Kenyan electorate were fully aware of the charges against Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto when they were elected.

"There needs to be a balance between the legal process and his right to govern," he said.

Boost for militancy?

In the event that the UN fails to delay his case and Mr Kenyatta opts not to attend his trial, observers believe a warrant of arrest would be issued, turning him, and Kenya, into something of an international pariah, like Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir.

Such an eventuality is fraught with serious political risks, including possible destabilisation, which would undermine regional counter-terrorism efforts.

"Leadership by Kenya is required to deal with regional instability," Mr Esipisu said, arguing that this was why African leaders had called for Mr Kenyatta's trial to be delayed.

If Kenya were to react by withdrawing from the fight against al-Shabab, that would be a massive boost to the Islamist cause in the region.

However, Kenya's constitution specifically states that officials indicted by international courts must co-operate, making a boycott difficult for Mr Kenyatta unless the UN Security Council comes to his aid.

And the stakes are also high for the ICC.

This is by far its biggest case and backing down would deliver a potentially fatal blow to the court, which has been heavily criticised for only delivering one conviction in more than a decade.

"In the long-term, the Kenya cases are existential for the ICC," Mr Boru said.

"Failure in the Kenyan case will cement the feeling the court, aside from targeting Africans, has also failed to get successful prosecution of big fish."

That leaves the UN Security Council trying to square the circle of delivering justice without potentially destabilising East Africa.

- Published11 October 2013

- Published10 September 2013

- Published5 December 2014

- Published27 May 2013

- Published12 December 2011

- Published7 February

- Published27 November 2017

- Published7 January 2015