Zimbabwe's new president Mnangagwa vows to 're-engage' with world

- Published

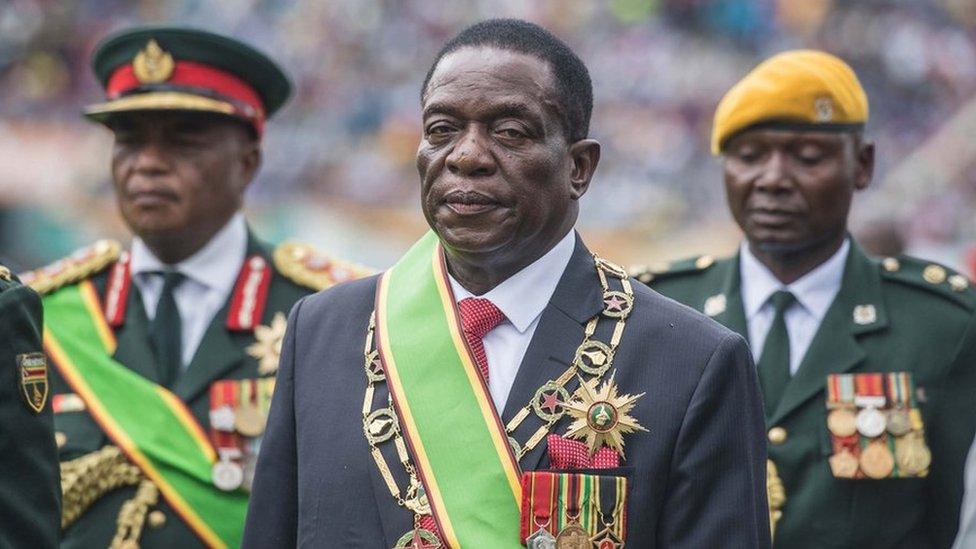

President Mnangagwa called Robert Mugabe "a father, mentor, comrade-in-arms and my leader"

Zimbabwe's new President Emmerson Mnangagwa has pledged to re-engage the country with the world, following the dramatic departure of Robert Mugabe.

In his inauguration speech, Mr Mnangagwa sought to reassure foreign investors to attract badly needed funds to revive Zimbabwe's failing economy.

And he also praised Mr Mugabe, calling him Zimbabwe's "founding father".

Mr Mnangagwa's dismissal as vice-president earlier this month led the ruling party and the army to intervene.

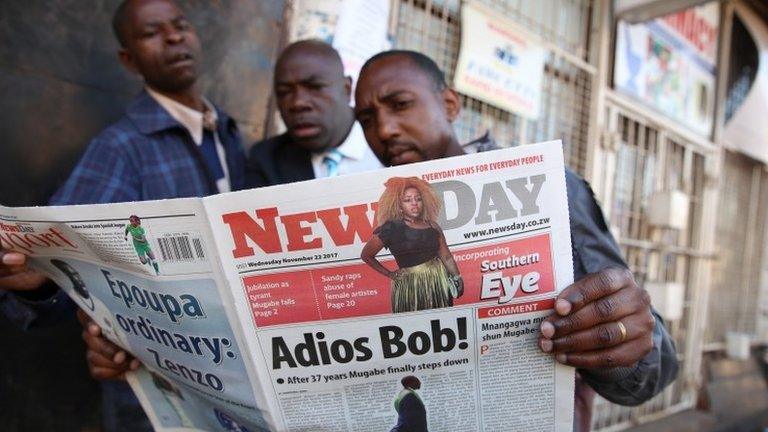

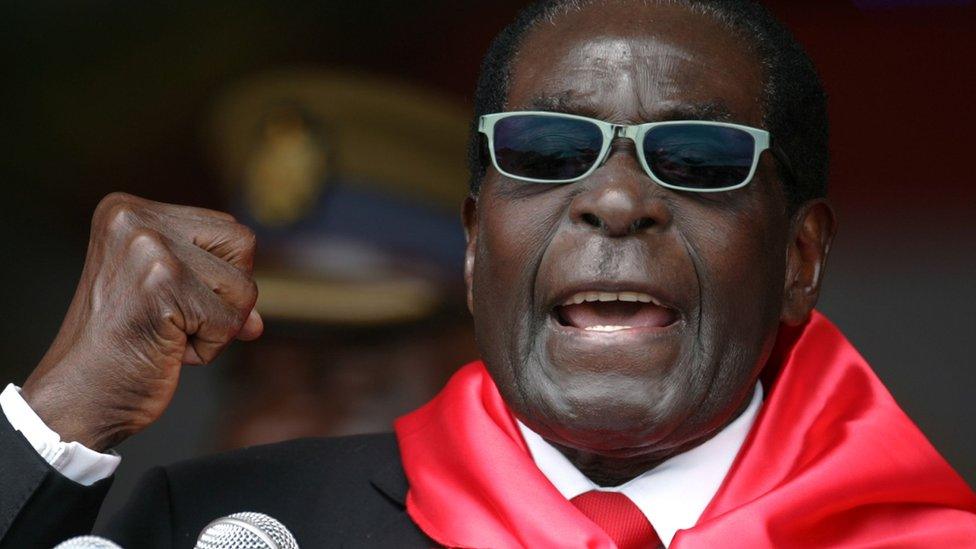

Mr Mugabe - who had wanted Grace Mugabe, the then-first lady, to take up the presidency - was forced to announce his resignation on Tuesday, ending 37 years of authoritarian rule.

What were the key messages in Mr Mnangagwa's speech?

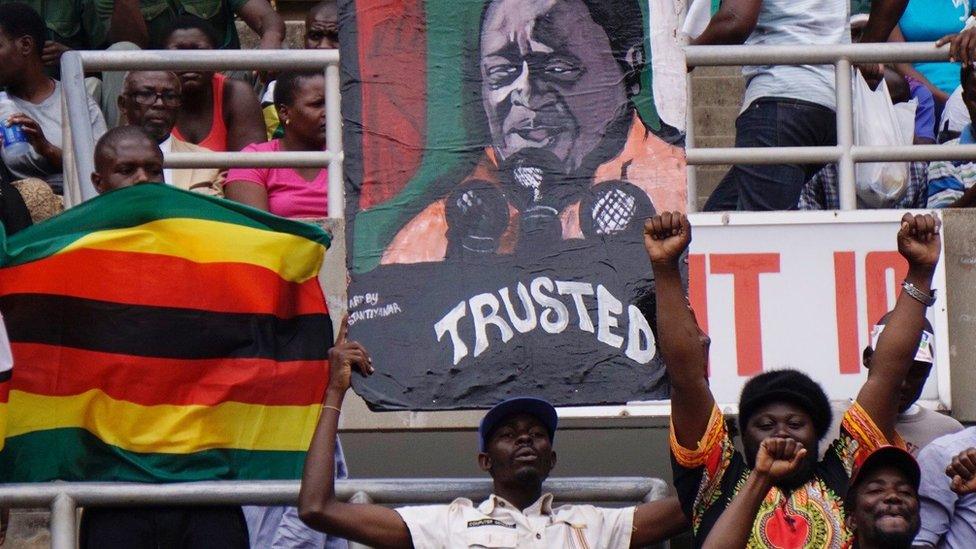

Addressing Harare's packed 60,000-capacity National Sports Stadium, the new leader said Zimbabwe was now "ready and willing for a steady re-engagement with all the nations of the world".

He said "key choices will have to be made to attract foreign direct investment to tackle high-levels of unemployment while transforming our economy".

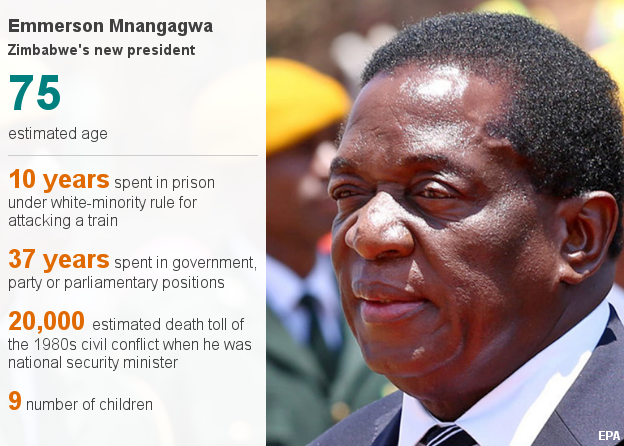

Emmerson Mnangagwa: Who is the man known as the ‘crocodile’?

And pledging a "new destiny" for Zimbabwe, he added: "Let us humbly appeal to all of us that we let bygones be bygones."

Mr Mnangagwa - who had fled the country earlier this month only to return to a hero's welcome on Wednesday - also said that:

Mr Mugabe's land reforms would not be reversed, but white farmers whose land was seized would be compensated

"Acts of corruption must stop", warning of "swift justice"

Elections scheduled for 2018 would go ahead as planned

He would be "the president of all citizens, regardless of colour, creed, religion, tribe, totem or political affiliation"

Mr Mnangagwa has for decades been part of Zimbabwe's ruling elite.

Despite his pledges, he is still associated by many with some of the worst atrocities committed under the ruling Zanu-PF party since the country gained independence in 1980.

He was the country's spymaster during the 1980s civil conflict, in which thousands of civilians were killed. His ruthlessness won him the nickname "the crocodile".

But Mr Mnangagwa has denied any role in the massacres, blaming the army.

Making all the right noises

Analysis by BBC Online Africa editor Joseph Winter

Emmerson Mnangagwa's speech of reconciliation will be widely welcomed in Zimbabwe, even if his powers of oratory fell well short of those of his predecessor.

He reached out to people across the "ethnic, racial and political" divides, following years of deep polarisation under Robert Mugabe.

However, those Zimbabweans who can recall the days before Mr Mugabe - the minority - will know that when he took power in 1980, he made similar pledges, and was widely praised for it, both at home and around the world.

What Zimbabweans really want is for Mr Mnangagwa to breathe new life into their failed economy.

Here, he also made all the right noises, recognising the severity of the problem.

He even promised compensation to the white farmers whose eviction caused the economy to spiral into free-fall. However, it is not clear where he would get the money from, and he did insist that land reform itself was non-negotiable.

He also accepted that he would not be judged on his speeches, but on his actions.

All Zimbabweans will agree with that.

Was Mr Mugabe present at the inauguration?

No - and the official reason given was that at 93, the former president needed to rest.

But the fact he did not attend is a reminder that this is no ordinary transition, the BBC's Andrew Harding reports, and that, despite Mr Mugabe's official resignation, he was forced out by the military.

On Thursday, several reports suggested Mr Mugabe had been granted immunity from prosecution.

Local media are reporting that Mr Mnangagwa has offered the Mugabe family "maximum security and welfare".

The former president "expressed his good wishes and support for the incoming president," the Herald newspaper reports.

How did Zimbabwe get to this point?

A pensioner, an activist and a white farmer share hopes for Zimbabwe's future

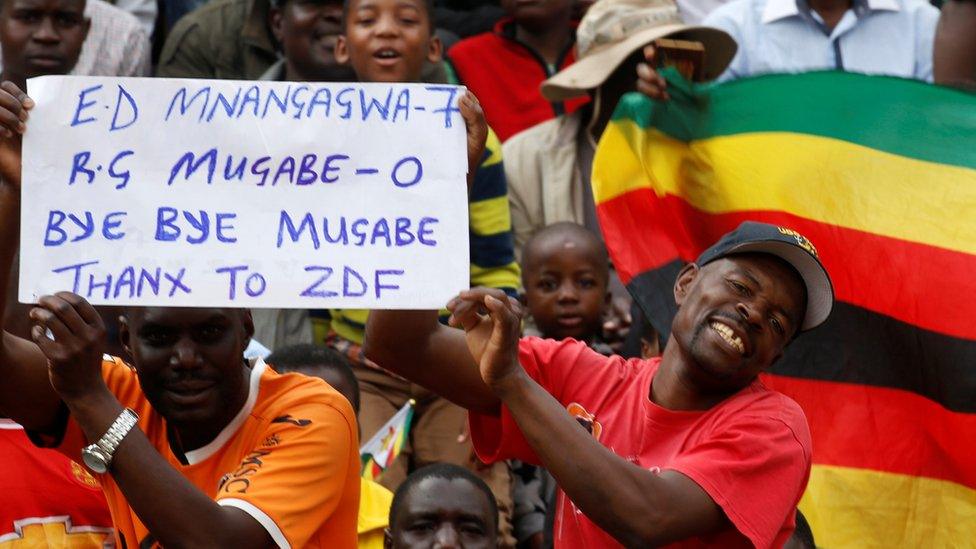

Tuesday's news that Mr Mugabe was stepping down - two days after Zanu-PF sacked him as its leader - sparked wild celebrations.

A resignation letter was read out in parliament, abruptly halting impeachment proceedings against him.

He had been under pressure since the military took control of the country a week before, seizing the headquarters of the national broadcaster.

Although Mr Mugabe was largely under house arrest for several days, he appeared to be resisting pressure to stand down.

On Saturday, tens of thousands of Zimbabweans took to the streets of Harare to urge him to go.

In his letter, he said he was resigning to allow a smooth and peaceful transfer of power, and that his decision was voluntary.

Will the change be good for the economy?

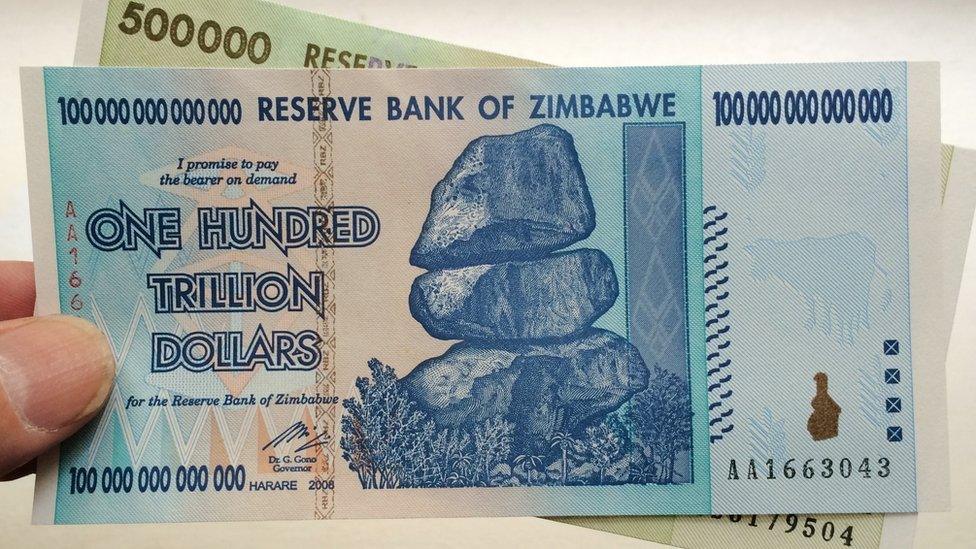

Zimbabwe's economy is in a very bad state. It has not recovered fully from crises in the last decade, when rampant inflation grew so bad the country had to abandon its own currency. Now, according to some estimates, 90% of people there are unemployed.

Leader of the opposition MDC party, Morgan Tsvangirai, warns of a "power retention agenda"

Its main industrial index has slumped by 40% since last week's military intervention and the stock market has shed $6bn (£4.5bn) in a week.

Analysts say the market is now correcting itself, optimistic of a change of economic policy under Mr Mnangagwa.

However, the International Monetary Fund has warned that Zimbabwe must act quickly to dig its economy out of a hole and access international financial aid.

- Published24 November 2017

- Published24 November 2017

- Published24 November 2017

- Published3 August 2018

- Published24 November 2017

- Published24 November 2017

- Published23 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published20 November 2017

- Published17 November 2017

- Published16 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published25 July 2018

- Published21 November 2017