Japan election: Shinzo Abe set for record tenure

- Published

Shinzo Abe, 60, has been Japan's prime minister since December 2012 after his Liberal Democratic Party's (LDP) landslide election win.

It was Mr Abe's second shot at the top job, after a brief term as prime minister from 2006 to 2007.

At that time, he was Japan's youngest leader since World War II but he stepped down citing ill-health as support for his administration plummeted.

Under him, a raft of measures have been introduced aimed at boosting Japan's struggling economy. Ties with China, however, have been tense over territorial and historic disputes.

When he won this year's snap election, it paved the way for him potentially to become Japan's longest-serving prime minister.

Early appeal

Known as a right-wing hawk, he hails from a high-profile political family. His father, Shintaro Abe, was a former foreign minister and his grandfather was former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi.

Mr Abe won his first seat in parliament in 1993. Appointed to the cabinet for the first time in October 2005, he was given the high-profile role of chief cabinet secretary.

When he became prime minister a year later, he was seen as a man in the image of predecessor Junichiro Koizumi - telegenic, outspoken and with a similar popular appeal to voters.

Abe's biggest competition in the 2017 election was from Yuriko Koike, governor of Tokyo and her Party of Hope

But a series of scandals and gaffes harmed his administration, including the revelation that the government had lost pension records affecting about 50 million claims.

A heavy loss for the LDP in upper house elections in July 2007 provided a catalyst for his decision to resign.

Second chance

He returned to Japan's political stage in 2012, renewing his mandate in the 2014 election and now again.

Mr Abe is best known for his muscular stance on Japan's defence, particularly in territorial rows.

In 2015 he pushed for Japan's right to collective self-defence, which is the ability to mobilise troops overseas to defend themselves and allies under attack.

This controversial change in law was approved by Japan's parliament but encountered significant opposition from the Japanese public, China and South Korea.

He hopes to amend the country's constitution by 2020 in order to formally recognise the military forces.

Mr Abe's push for collective self-defence met significant opposition among the Japanese public

His administration has been plagued by political scandals and falling popularity but he was buoyed in the election by opposition chaos, and over regional security concerns amid increasing tensions.

He could remain in office until 2021 if his party re-elect him, having altered their rules to allow for a third term.

Mr Abe has promised strong "counter-measures" against North Korea, after they fired missiles over Japan. But he did not elaborate what this meant in practical terms and his administration has had a poor relationship with North Korea's closest ally, China.

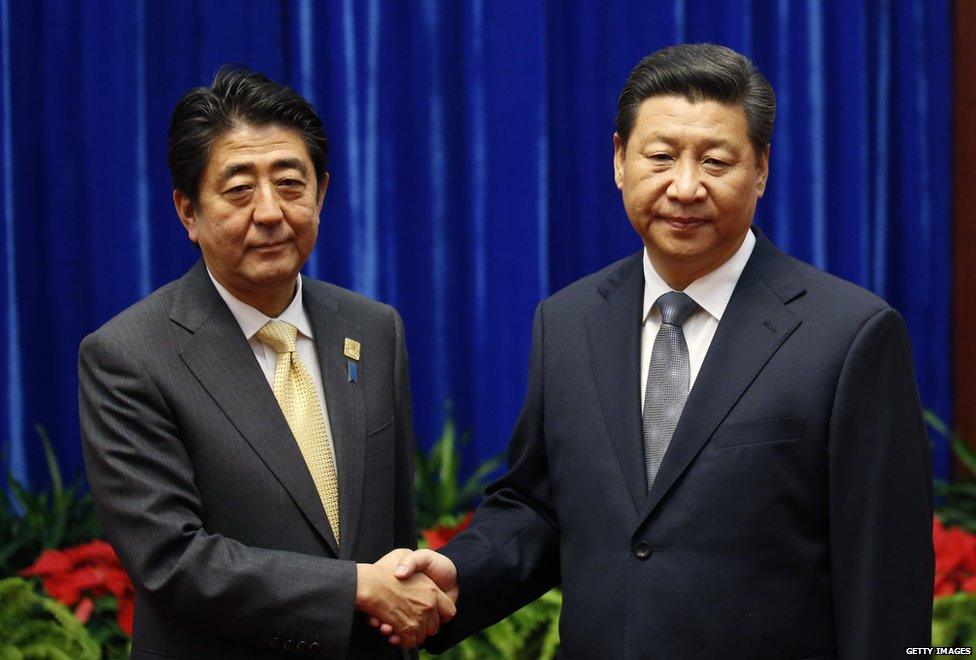

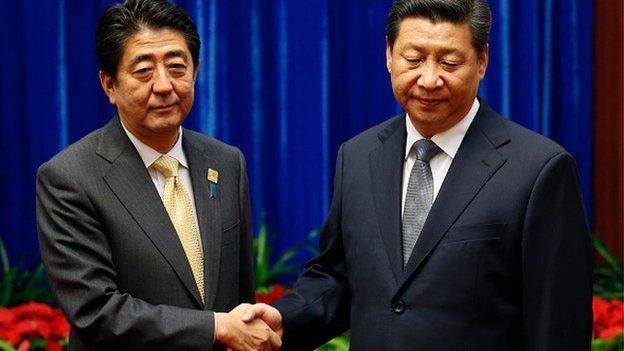

Relations with China's President Xi Jinping (right) remain chilly

Mr Abe has visited the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, which commemorates Japan's war dead including war criminals, on several occasions, angering regional neighbours.

China-Japan relations chilled over such issues, as well as the continued dispute over islands in the East China Sea.

He attended an event in September 2017 to commemorate 45 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries, in a move interpreted as a potential olive branch between the nations.

Tokyo's stock market went on a record-breaking streak in the run-up to Abe's 2017 victory

At home, Mr Abe put into place a series of measures known informally as "Abenomics" - monetary policy, fiscal stimulus and structural reforms - aimed at boosting Japan's long-stagnating economy.

The measures initially worked in boosting GDP growth but the country has failed to meet the ambitious targets he sent out back then. The results of his economic policy have been deemed as mixed.

To solve a labour crunch caused by a declining and ageing population, Mr Abe has tried to push for more women to re-enter the workforce.

But the campaign has had limited success due to longstanding cultural norms where women quit their jobs after having children and are deterred from rejoining the workforce because of Japan's punishing work culture.

The country's unemployment levels are the lowest they have been in decades but salaries have failed to grow with the country's exporting success.

- Published11 December 2014

- Published17 November 2014

- Published10 November 2014

- Published1 July 2014

- Published19 July 2013

- Published26 December 2013