Rodrigo Duterte's undiplomatic diplomacy rattles Asean

- Published

The Asean summit is typically a ho-hum affair, pre-scripted and well rehearsed. No one steps out of turn, or does anything to draw too much attention to the event.

The discussions by leaders of the Association of South East Asian Nations (Asean) are usually non-confrontational, the decisions are consensus-based and everything is extremely polite. Leaders pose for a photo, shake hands and head home after a couple of days in the sun.

That is - until Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte came into the picture.

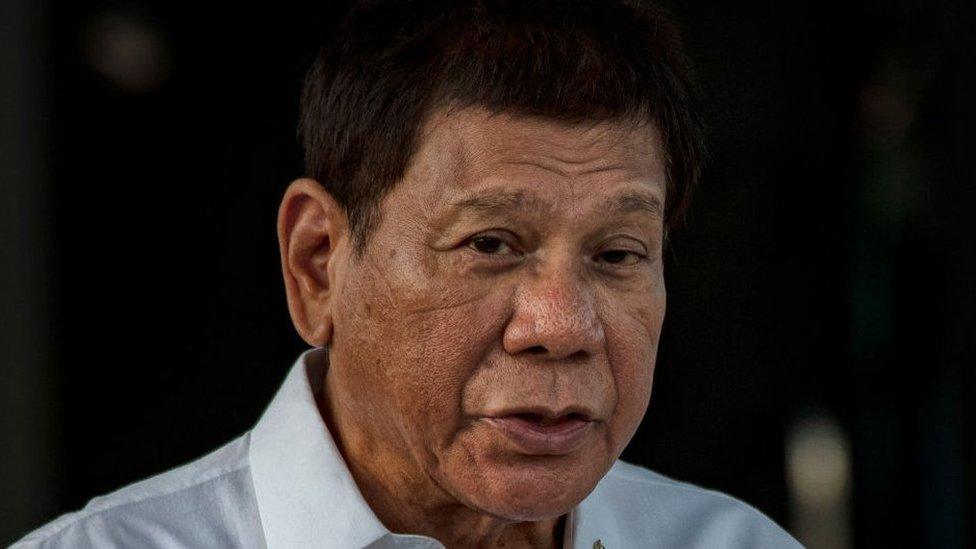

Brash, outlandish, with his sleeves rolled up - he is everything a typical Asian diplomat is not.

Which is why some here at Asean have expressed concern over his behaviour.

I walked into a gaggle of Filipino journalists, all heatedly debating their president.

Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte's diplomatic style has raised brows at the Asean summit in Laos

"He was right to tell the US to mind their own business," said one. "We shouldn't have to listen to anyone."

"An insult is an insult," said another. "Will he insult the Chinese leaders too?"

World leaders' offensive insults: Who's top?

Duterte: From 'Punisher' to president

Some of Duterte's most contentious quotes

The spat dominated discussions at the summit on Tuesday, although it is unlikely to hijack the work of the entire gathering. And it seems to have simply confirmed fears about Mr Duterte and his conduct at such an event.

The argument between the US and the Philippines was ostensibly about whether Mr Obama would raise the issue of extrajudicial drug killings with Mr Duterte, but actually, it is about a lot more.

At the heart of this issue is the rise of a newly influential China balanced against an established power - the United States - and where Asean falls into the mix.

In his speech to the Asean leaders, President Obama stressed the long-term commitment of the US to the region

Mr Obama is coming to Laos from China, where he had to suffer the indignity of "Carpetgate" as it has been dubbed - when China literally failed to roll out the red carpet for him when he arrived at the G20 in Hangzhou.

Mr Duterte's rude behaviour has shades of Hangzhou in it, but the Philippines does not want to be under China's influence either.

Like most of the other Asean countries, the Philippines needs the US - it is a key ally, both politically and economically.

This contradiction is being played out across the region.

Economically, Asean is increasingly living in the shadow of China. Many countries in the region count China as their biggest trading partner and investor. And while there have been a few exceptions, most have been remarkably timid about China's sometimes overbearing dominance - especially with regards to the South China Sea.

Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang may be asked about the man-made islands in the South China Sea

But neither can they ignore the United States. So Asean has to strike the right balance between these two giants - which is why Mr Duterte's diplomatic faux pas was quickly rectified by an expression of regret that the strong comments he made were seen as a personal attack on President Obama.

That did not stop the US from cancelling the planned bilateral meeting - frankly, if Mr Obama had gone ahead, it would have been seen as a sign of weakness, not just by Asean leaders but also by China.

But Mr Obama was also keen to stress the long-term commitment of the United States to this region.

In his speech he talked of the different countries he had visited in his years in office and, in classic Obama style, peppered local phrases to display his knowledge of Laos.

He also used the opportunity to make his last pitch for the US to continue its engagement in Asia. "We are here to stay," he told an applauding audience in the Laotian capital Vientiane. "In good times and bad, you can count on the United States of America."

But increasingly in these parts, the same could be said of China. How this struggle between Asean, the US and China plays out will shape the region in years to come. Which means perhaps at future Aseans, Mr Duterte's diplomatic gaffes will not be the only thing we pay attention to.

- Published11 March

- Published21 August 2016

- Published26 August 2016