North Waziristan: What happened after militants lost the battle?

- Published

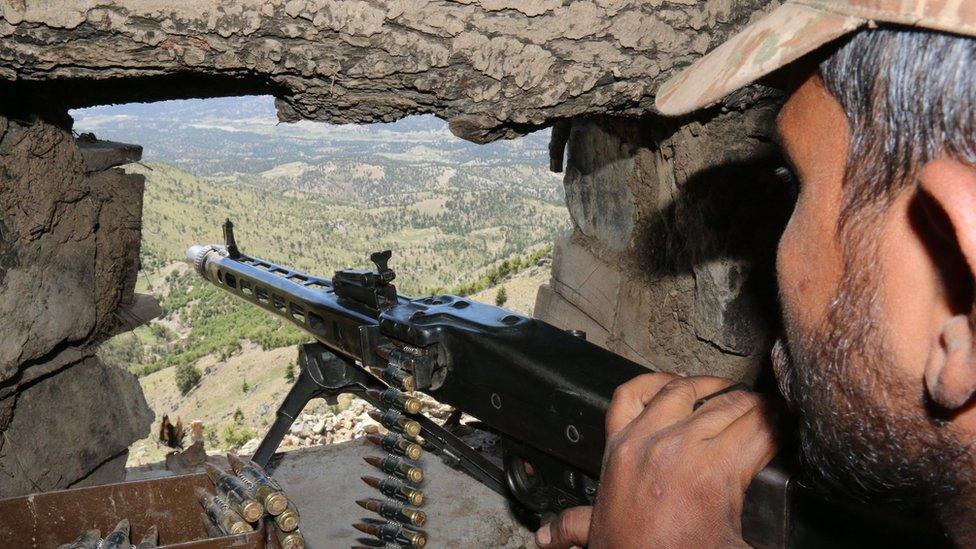

Pakistani troops cleared militants from North Waziristan in a long, bloody campaign

For over a decade the inaccessible and mountainous tribal area of North Waziristan was home to a swirling array of violent jihadists.

The Pakistan and Afghan Taliban movements, al-Qaeda and less well-known militant outfits such as the Haqqani Network used the area to hold hostages, train militants, store weapons and deploy suicide bombers to attack targets in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Today the militants have gone. Virtually the whole of North Waziristan is in Pakistani army hands.

The army believes the defeat of the militants was one of the most successful anti-jihadist campaigns the world has yet seen. In two years of fighting the army lost 872 men and believes it killed over 2,000 militants.

"Before 2014 North Waziristan was a hub of terrorist activities," said General Hassan Azhar Hayat, who commands 30,000 men in North Waziristan. After the army moved in "those who resisted were fought in these areas… the complete agency was cleared".

But many militants managed to escape, slipping across the border to eastern Afghanistan to fight another day. Many are now operating there with impunity, some helping the Afghan Taliban in its battle against the government in Kabul while others attack targets in Pakistan.

The latest group to establish itself in the area is Islamic State, although the degree of control exercised by Iraq-based Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi over his supporters in Afghanistan is unclear.

When the jihadists fled North Waziristan they left behind the apparatus that had helped keep their movement in power.

Pakistani army officers today jokingly refer to one village, that was home to many senior militant commanders, as the Taliban's Pentagon, and they describe another where militants were trained as the Taliban Sandhurst.

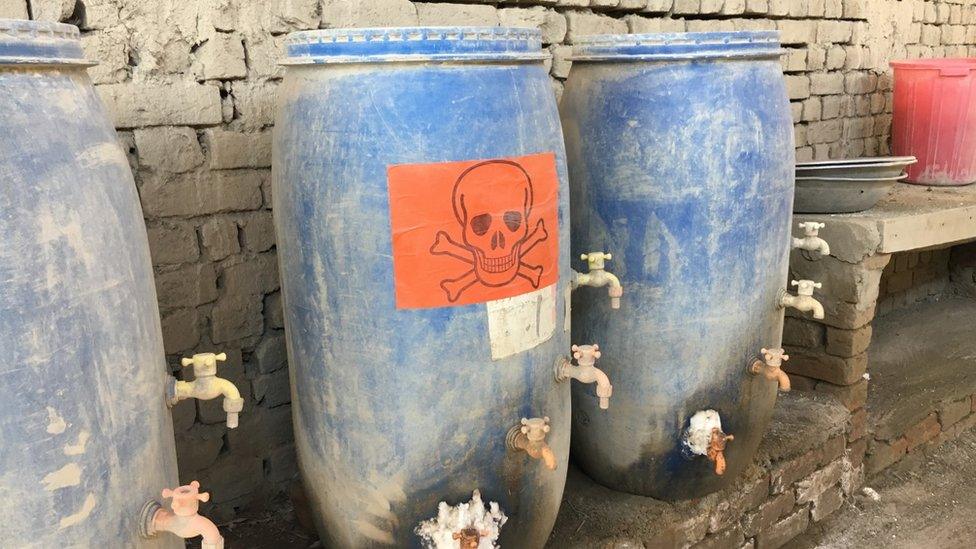

As they moved across North Waziristan, the army found prisons, a media centre hidden under a mosque, bomb-proof tunnels and a huge roadside bomb factory.

With hundreds of bags of fertiliser and large blue plastic vats filled with foaming chemicals, the facility turned out thousands of bombs that were used all over Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The closure of the roadside bomb factory, and others like it, has made a difference. Last year there were 441 violent jihadist attacks in Pakistan. That compares with 2,586 attacks in 2009.

Across North Waziristan as a whole the army found 310 tons of explosives and more than two million rounds of ammunition.

Troops found a sophisticated military set-up in North Waziristan, including bomb factories

These bomb factories made devices for use in terror attacks across the nation

Border watch

For many years, when it was accused of offering sanctuaries to the Afghan Taliban, Islamabad used to argue that it was unable to prevent militants moving into Afghanistan to launch attacks.

It was impossible, Islamabad said, to control such a long, remote and porous border over which villagers with relatives in both countries moved freely.

But now it is faced with the mirror situation - Afghan-based militants carrying out attacks in Pakistan and the army trying to control the border. The army says more than 1,000 forts have been built and sophisticated American radar equipment installed to monitor cross border movements.

The situation at the border is complicated by the fact that, while Pakistan considers it to be a legitimate international border, Afghanistan has never accepted it as such.

Pakistan keeps a major military presence in North Waziristan and along the border with Afghanistan

Some of those who fled North Waziristan at the height of the unrest are now starting to return

The battle for North Waziristan - like those for Mosul and Aleppo - has left widespread destruction. Many homes have been reduced to rubble. There are whole villages where no building has a roof on it.

"When we came back we faced the problem of no electricity and water," said Saifur Rahman, who spent several months living in the nearby town of Bannu during the worst of the fighting between the army and the militants.

But he had been determined to return. "This is our land. We love it and I don't care if the facilities aren't there. I will still come back."

The army is now building infrastructure to tempt people to return. As well as new roads, there are brand new schools with facilities that rival anything on offer elsewhere in Pakistan.

One of the recently constructed and very well equipped schools just outside Miranshah is currently completely empty but has places for 1,000 children when the families decide to return.

Jihadist violence is not over in Pakistan. The state is not moving against some of the militant groups that concentrate their activities in Kashmir, Afghanistan and India. And Afghan-based militants from the Pakistani Taliban and other groups remain a potent force.

A recent attack on a Sufi shrine in the province of Sindh killed over 80 people. Police in Karachi say they believe the attack was organised by Afghan-based militants.

But for all their latent power, the militants in North Waziristan have been repulsed from their stronghold and the tribesmen are gradually returning to resume lives disrupted by conflict.

- Published10 July 2014

- Published17 February 2017

- Published1 February 2017

- Published25 February 2017