Face-to-face with top North Korean diplomat

- Published

The BBC’s John Sudworth asks North Korea’s vice-foreign minister what message he has for Donald Trump

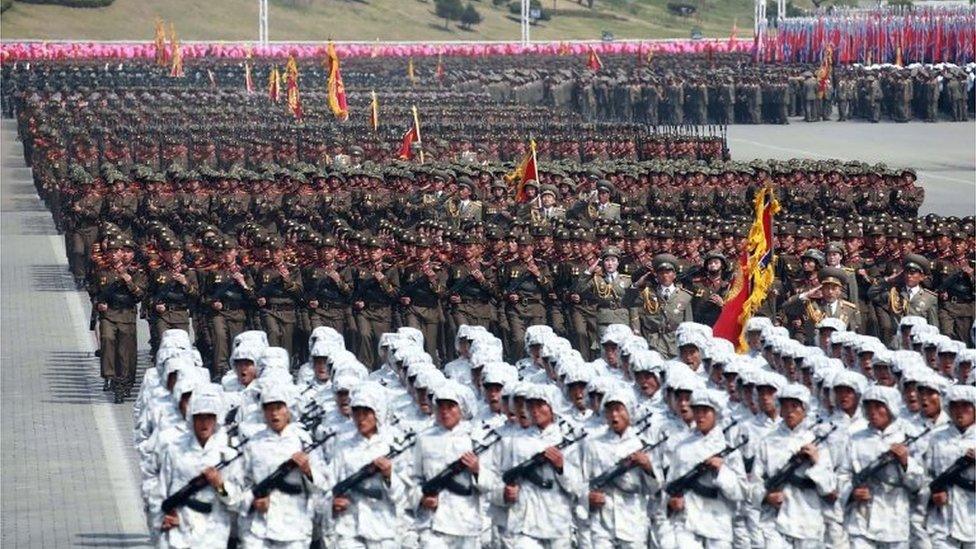

Two days ago, I stood on the edge of Kim Il-sung Square in the centre of Pyongyang and watched, with a mixture of awe and unease, as North Korea's giant military parade passed by.

Back in that same location today, the vast space of the square was almost empty except for a few government workers on foot and the odd car - which pretty much sums up the traffic situation, or lack of it, in this isolated, sanction-hit city.

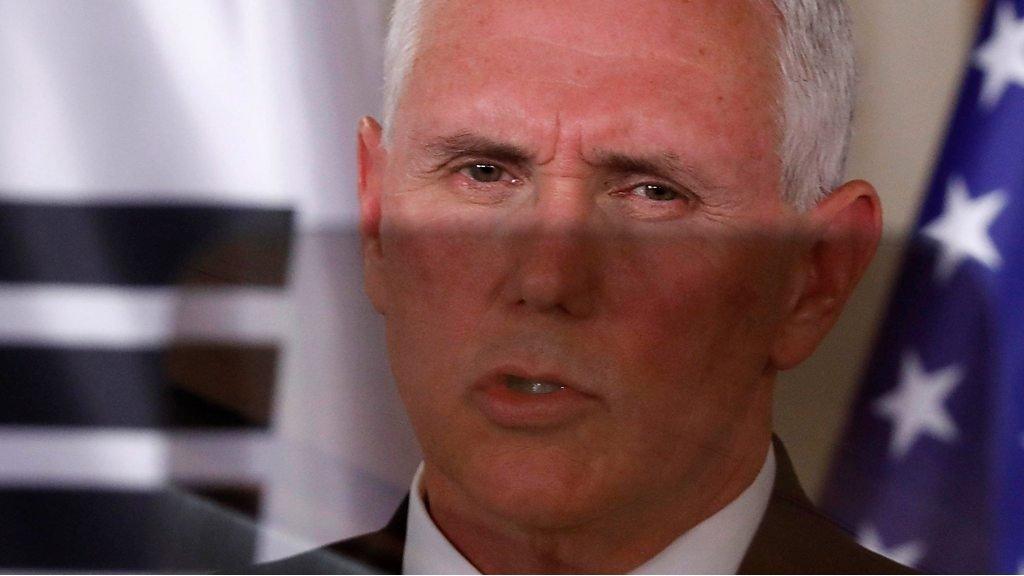

My government minders ushered me up the steps of the foreign ministry and I soon found myself sitting face to face with Vice-Foreign Minister Han Song-ryol.

Were some of the weapons on display in the parade, as many analysts have speculated, new intercontinental ballistic missiles? I asked him.

"The respected Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un in his historic new year address this year said that we are at the final stage of preparations to launch an ICBM (Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile)," he replied.

"I'm no military expert," he went on, "but I hope that there was an ICBM among the missiles shown at the parade."

The BBC's John Sudworth, in Pyongyang, explains what may happen next

North Korea needs such weapons, he said, "in order to protect our government and system from threat and provocation from the United States".

And in a direct riposte to US President Donald Trump and his assertion that North Korea will not be allowed to develop nuclear weapons, Mr Han added this.

"According to our own schedule we'll be conducting more tests on a weekly, monthly and yearly basis."

'Reckless option'

North Korea has long been seen to use provocation and brinkmanship to raise tension for its own strategic advantage.

It is then able to win diplomatic and economic concessions through negotiations to defuse the crisis, only later to go on to renege on its disarmament commitments.

As the cycle begins again, at each stage, it moves a step closer to its goal of becoming a fully-fledged nuclear power.

But while the current state of technological advancement of North Korea's weapons programme matters deeply to the outside world, in particular its near neighbours, the hostile rhetoric is rarely something to take at face value.

Read between the lines and, mostly, it is always conditional, peppered with ifs and buts, as it was today.

"If the US goes on with their reckless option of using military means then that would mean from that very day, an all out war," Mr Han told me.

The interview does though give a hint of the new worrying unpredictability at play.

Donald Trump's recent ordering of the airstrike on a Syrian airbase has clearly rattled Pyongyang and the threat now is not simply of retaliation to an attack, but even, Mr Han suggests, to the planning of one.

"If the USA encroaches upon our sovereignty then it will provoke our immediate counter reaction and if it is planning a military attack against us, we will react with a nuclear pre-emptive strike by our own style and method."

Experts say an all-out war is very unlikely

However, despite the posturing on both sides, the risks, most observers agree, are still limited.

For the US and its allies, war carries incalculable risks and although Washington insists that all options are on the table, it now appears to be signalling that diplomacy and toughened sanctions are the most likely way forward.

It is as yet unclear how, having failed before, those things will force this most totalitarian of states to give up its nuclear weapons.

As Vice-Foreign Minister Han made clear to me, North Korea has learned the lessons from recent history, in particular the US-led attempts at regime change in Iraq and Libya.

"If the balance of power is not there, then the outbreak of war is imminent and unavoidable."

"If one side has nukes and the other side doesn't, and they're on bad terms, war will inevitably break out," he said.

"This is the lesson shown by the reality of the countries in the Middle East, including Libya and Syria where people are suffering from great misfortune."

The vice-foreign minister said North Korean people are guaranteed their human rights

Within the city limits of Pyongyang, foreign journalists get to see very little of ordinary life on these carefully choreographed and highly controlled media tours.

Even further beyond reach, good evidence shows, lie the vast political prisons in which all dissent and opposition to the system, however mild, is crushed.

Rather than building nuclear weapons, I ask Mr Han, wouldn't North Korea be better improving life for its own people, perhaps starting with abolishing those gulags?

"We do not tolerate any others criticising our style of socialism and we believe in the choice we have made," Mr Han replies.

"The masses are the centre of our state and their security and human rights are guaranteed."

"As for the so called political prison camps you have just mentioned," he went on, "it is something that our enemies have fabricated and it has been disseminated by their followers in order to demonise our country".

The message is clear.

Militarised and isolated, North Korea has the right to follow its own path and, Mr Han apparently believes, no one will be able to stop it.

So far, he has been proven right.

- Published17 April 2017

- Published18 April 2017

- Published17 April 2017