China's hypersonic missile: Could it spark a new arms race?

- Published

China's hypersonic glide vehicles featured in a 2019 Beijing parade

The news that China had tested a new nuclear-capable hypersonic missile was described by some as a game-changer that stunned US officials. So how big a deal is this, asks Jonathan Marcus of the Strategy and Security Institute, University of Exeter.

Twice in the summer, the Chinese military launched a rocket into space that circled the globe before speeding towards its target.

On the first occasion, it missed its target by about 24 miles (40 km), according to people briefed on the intelligence speaking to the Financial Times, external, which broke the story.

While some US politicians and commentators were alarmed at China's apparent progress, Beijing was quick to deny the report, insisting that this was in fact the test of a re-usable spacecraft.

China's denial is "an act of obfuscation" says Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Non-Proliferation Program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, California, because the story has been confirmed by US officials speaking to other media.

And he finds the claim that China tested an orbital bombardment system [FOB] both "technically plausible and strategically reasonable for Beijing".

What are ICBMs and FOBS?

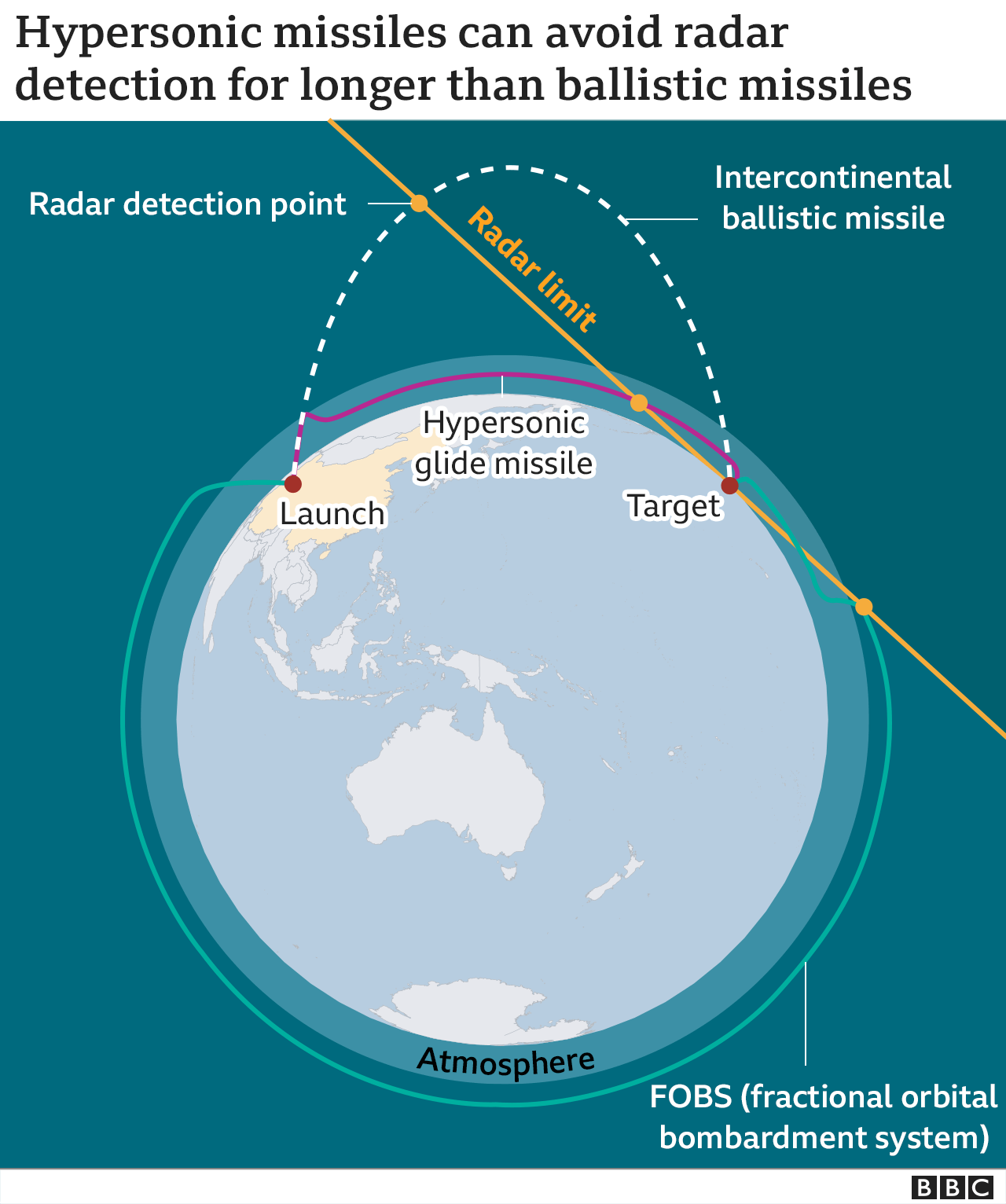

An ICBM is a long-range missile that leaves the earth's atmosphere before re-entry, pursuing a parabolic trajectory towards its target

A Fractional Orbital Bombardment System sends missiles through a partial orbit around the earth to strike targets from an unexpected direction

Both the FT story and the Chinese denial could be right, says Aaron Stein, director of research at the Foreign Policy Institute in Philadelphia.

"A reusable space plane is a hypersonic glider. It just lands. A FOB system delivered via some sort of glider would do much of the same thing as a reusable space plane, so I think the actual differences between the two stories is marginal."

Indeed over recent months a number of senior US officials have hinted at this kind of Chinese development.

FOB systems are not by any means new.

The idea was pursued by the Soviet Union during the Cold War and is now seemingly being revived by China. The idea is for a weapon that enters a partial orbit around the earth to strike targets from an unexpected direction.

What China appears to have done is to combine the FOBS technology with a hypersonic glider - they glide along the outer edge of the atmosphere avoiding radar and missile defences - into a new system. But why?

"Beijing fears that the United States will use a combination of modernised nuclear forces and missile defences to take away their nuclear deterrent," says Mr Lewis.

"If the US were to strike Beijing first, which we publicly retain the option of doing, the missile defence system in Alaska might be able to handle the small number of China's nuclear weapons that survive."

All the major nuclear players are developing hypersonic systems but view them differently, says Aaron Stein. And these differing points of view, he argues, feed into the other sides' paranoia, fuelling the arms race.

Both Beijing and Moscow view hypersonics as a means to ensure the defeat of missile defences, he believes. But in contrast, the US plans to use them to strike so-called hard targets like things that support nuclear command and control, using conventional or non-nuclear warheads.

Russia's Avangard hypersonic boost-glide weapon

Some advocates of rapid US nuclear modernisation have seen the recent Chinese tests as "a Sputnik moment" a reference to the surprise and alarm registered in the US at the Soviet Union's first orbital satellite in the late 1950s.

But some experts would disagree and don't believe this test by China creates a new threat. James Acton of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace says the US has been vulnerable to nuclear attack by China since at least the 1980s.

But he thinks intensive Chinese, Russian and North Korean programmes to defeat US missile defences should prompt the US to reconsider whether treaties that impose limits on such defences are, after all, in the US interest.

Mr Lewis stresses that the important thing now is for the US to draw the right conclusions.

"I fear this is much more like 9/11 where in the aftermath of the surprise and reeling from a mix of fear and vulnerability, we embarked on a series of disastrous foreign policy decisions that made us far less safe.

"In fact, one of the things that we did was to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile or ABM Treaty, which is far more responsible for China's development of this system than anything else."

Nuclear weapons: Explained in numbers

America's potential adversaries are all seeking to modernise and upgrade their nuclear weaponry.

China's arsenal, though, is still dwarfed by that of the United States. But concerns about US missile defences and conventional precision long-range strike systems are all pushing it to develop a larger and more diverse nuclear arsenal.

North Korea too is seeking to modernise and refine its nuclear capability, not least, as Ankit Panda of the Carnegie Endowment notes, to secure added leverage in future diplomacy.

"For a few years now," he says, "they've demanded to be treated by the United States as an equal and see the development of ever-more-advanced nuclear and missile capabilities as one way to earn that respect."

Putin and his defence chiefs watch a hypersonic missile launch via video link

It all contributes to a growing nuclear headache for the Biden administration.

The collapse of much of the existing fabric of arms control agreements inherited from the Cold War does not help. Neither do the growing tensions with both Moscow and Beijing.

In Ankit Panda's view, the single most meaningful thing the United States could do to stem and slow the ongoing arms race is to discuss limitations on strategic missile defences, as it did during the Cold War.

"Putting missile defence on the table"' he says, "would allow Washington to extract meaningful concessions from Russia and China. It would additionally dissuade each from pursuing costly, convoluted, and dangerous means to deliver nuclear weapons."

Jonathan Marcus is honorary professor at the Strategy and Security Institute, University of Exeter, UK