Hong Kong police: We don’t need Beijing’s help

- Published

Hong Kong's police say they have a grip on the protest movement

Hong Kong's police say they were stretched and struggling.

Months into a city-wide rebellion calling for democratic reform, activists had changed tack, hitting many targets at once. They couldn't keep up.

But they have now reorganised operations and say they are on top of the situation, making it unlikely mainland troops will be seen on the city's streets.

This information came from a nearly three-hour briefing this week, given by senior police officers to international journalists, including the BBC.

They gave an unusually frank assessment on their capabilities and the likelihood of an intervention from Beijing. They say it won't happen and this is why.

Could China take over?

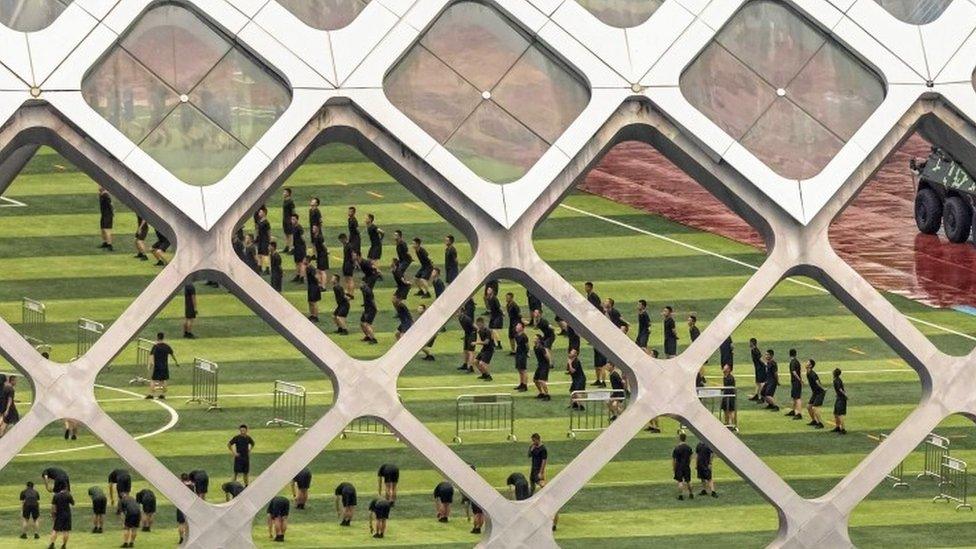

If, at some point, this city's evolving crisis deteriorates to a level beyond the reach of the local authorities, this could mean mainland riot troops coming across from the border city of Shenzhen.

Images of the People's Armed Police arriving in convoys have been published by Chinese state media, accompanied by threats of intervention.

If this happened, "we'd be in completely new territory", a senior Hong Kong police officer said and his colleagues nodded in agreement.

He said there was no capacity for interoperability between mainland forces and Hong Kong police. There are no protocols, no plans. They have never even had joint training.

How Hong Kong got trapped in a cycle of violence

This would seem to suggest that if troop trucks start driving into Hong Kong, it means the Chinese government are taking control of the operation.

A senior officer we spoke to was adamant that "it won't happen". Hong Kong police "can handle" the current crisis, he said.

He added that speculation on social media that mainland Chinese police were already within their ranks - spurred partly by some officers not showing their identification numbers and rumours of Mandarin Chinese being spoken - was totally false.

China's ambassador to the UK, Liu Xiaoming, warned on Thursday that Beijing could "quell any unrest swiftly", and accused unidentified "foreign forces" of inciting the protests.

Members of China's People's Armed Police practise in Shenzhen, near the border with Hong Kong

However, on this point, they were also frank.

When we asked if police had seen any evidence to back up the allegations that foreign governments had either funded or organised the anti-government protests, the answer was straight to the point: "No."

Undercover police officers

Hong Kong police admit that, at one point, they were stretched too thin to respond to the number of moving protests, with hardline activists adopting a "hit-and-run" strategy. They would hurl bricks at a police station or block a cross-city tunnel and then, when the riot teams arrived, they would run.

During a widespread strike on 5 August, there were clashes in a dozen sites across the territory.

Police say they can now send out teams much more quickly - that they are more mobile, and have taken advantage of protesters breaking into smaller groups by moving in fast to make arrests.

The authorities can call on some 3,000 trained riot police, who normally have other roles within the 30,000-strong police force.

They also feel more confident because they have apprehended what they call significant figures among the most radical protesters.

While this movement has been described as leaderless, relying on consensus-building within chat groups, police feel that key people have been able to sway support for certain types of actions.

They say they've been able to find and grab these "main players" with the help of intelligence gathered by undercover officers placed within the ranks of the protesters. They sometimes call these "decoy operations".

'If they killed somebody, they would face murder charges'

The use of undercover police has led to concern and even paranoia among groups of protesters.

On Tuesday, activists attacked two men - including a Chinese state media journalist - at Hong Kong's airport, accusing them of being mainland officers.

On all sides, people are becoming much more cautious who they trust, including journalists. Both the police and protesters often want to see some ID before talking to you.

Pro-Beijing supporters show support for the Hong Kong police during a pro-government rally

Police have also come under fire for what - at times - is seen as a heavy-handed approach, including the use of tear gas in residential areas and underground train stations.

Then there are images that seem to show riot teams firing rubber bullets and tear gas horizontally - at head-shot range - straight into crowds of activists.

Police said this should not be happening. "Baton round" rubber bullets are to be fired at the ground and the idea is that they then ricochet into people.

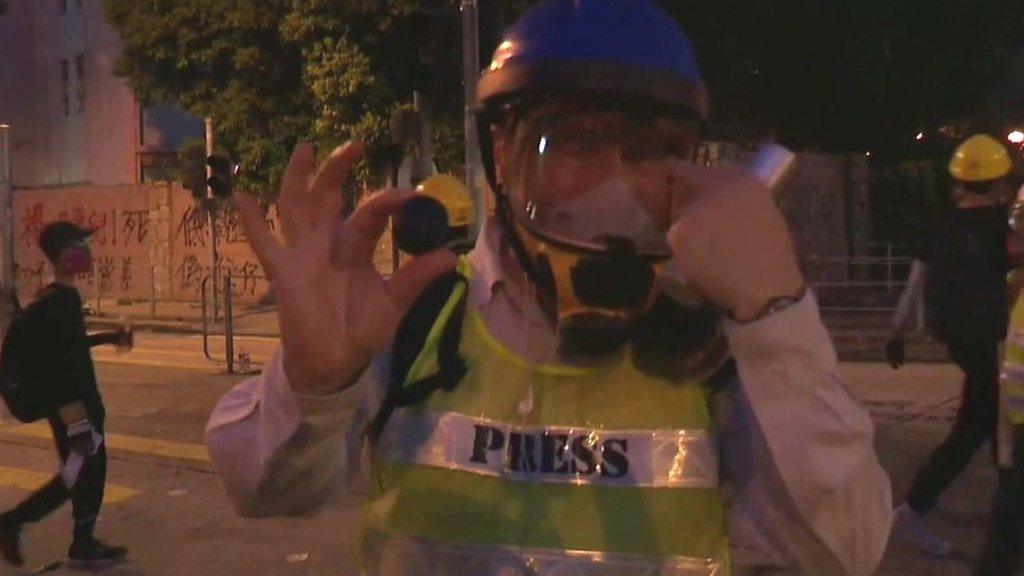

This could be what happened to me on 5 of August when a projectile - police say most likely a rubber bullet - hit me straight in the face, smashing my tear gas mask.

One of the officers told me he did not think I would have been deliberately shot in the head. "At least I hope not," he said.

He added that it was more likely a round bounced up at me from below and that it was just unfortunate to strike me where it did. Who knows?

Another officer told me that police would be crazy to fire at somebody's head with any type of round. "If they killed somebody, they would face a murder charge," he said.

The Special Tactical Contingent - a riot team known as the "Raptors" - were filmed last weekend chasing protesters into an underground train station and, at the top of an escalator, firing non-lethal rounds at activists from point-blank range, then laying into them with batons.

The BBC's Stephen McDonell observes the new quick-moving tactics of the Hong Kong police against protesters.

The police are making no apologies for this response given, they say, the violent attacks against their own officers who have had bricks and metal bars thrown at them.

Then there is the use of tear gas which is beyond its use-by date. We asked if reports were true that this could be harmful.

These officers told us manufacturers have assured them it is completely safe - however, to be sure, they would be recalling any expired canisters.

Given how much tear gas they are firing, does this mean they could run out?

"No."

Fears of retribution

There is also a really crucial question regarding their long-term future: how can they start to rebuild public trust?

The officers we met shook their heads and shrugged. "It's going to take a long time to be honest," one said.

Probably the worst public-relations disaster for the police came on 21 July, when they were nowhere to be seen as triad-connected gangs of men, dressed in white, waited for protesters at Yuen Long train station and proceeded to assault them with home-made weapons. Passers-by were also caught up in the attacks.

A large group of masked men in white T-shirts stormed Yuen Long station

Although police have now made dozens of arrests among the "white shirts", many in the general public and especially among the pro-democracy camp, are calling for an independent inquiry into recent events, including alleged links between some officers and underworld gangs.

Hong Kong's leader Carrie Lam has rejected the need for such an inquiry, saying that the Independent Police Complaints Council is already looking at the matter.

The officers we spoke to also said there was no need for a dedicated independent inquiry.

Even when we asked them whether this might be a way to win back public trust, they said they couldn't see the value in it.

In the meantime, police on the ground are coming under enormous personal pressure.

After a full day of street battles with protesters, they have routinely been surrounded in the street by ordinary citizens in their hundreds hurling abuse at them.

"The sound has been deafening," said one of the officers we spoke to.

There is also cyber-bullying. At least 300 officers have had their personal information placed online; photos of their children have been published and groups go to the workplaces of their wives or husbands, just to let them know they are aware of who they are.

We were told about one teenage daughter of an officer who was harassed by an adult while she was playing sport. They said to her: "What your father is doing is disgusting."

Activists have cut electricity to police homes and sent fake food deliveries to them in the early hours of the morning.

Protesters make barricades at Hong Kong airport

The fear of being identified for retribution is so high, we were told, that when police go to hospital for treatment, some of them describe their occupation as "public servant" rather than "police officer".

They fear hospital records could be leaked or even that they could be harassed in hospital.

'We can't get involved in politics'

Only a political solution can ultimately ease Hong Kong's crisis.

Those who can bring this about are not on the front lines. This is the realm of police and activists.

Would these officers like to see some sort of action from the city's leaders, especially Chief Executive Carrie Lam, to take the heat off the police?

They smile. It looks like they really would like to say more - but instead, after a brief pause, we are told: "We can't get involved in politics".

The say they want protesters to return to demonstrating peacefully - "the Hong Kong way".

Carrie Lam is asked: "Do you have the autonomy or not to withdraw the extradition bill?"

But tens of thousands of activists here now believe that peaceful protest has been ignored by those in power and that escalation is the only option to somehow bring about democratic reform.

The police know this is not going to end soon.

There has been an increased number of resignations from the force as a result of this crisis, we were told.

But the biggest impact, they say, has been for officers to pull together and support one another.

Is there any possibility that the protest movement has created divisions within the force?

Not a chance, they say. Exactly the opposite.

What questions do you have about Hong Kong? Let us know and a selection will be answered by a BBC journalist.

Use this form to ask your question:

If you are reading this page on the BBC News app, you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question on this topic.

- Published16 August 2019

- Published17 August 2019

- Published5 August 2019

- Published15 August 2019

- Published14 August 2019

- Published16 August 2019