Kashmir: Letters and landlines return to cut-off region

- Published

Landline phones are being slowly restored in Kashmir

In neat cursive handwriting, a woman from Delhi wrote a letter to friends in Indian-administered Kashmir last month.

She had visited them on a holiday in July. Now, she was desperately trying to find out how they were doing.

"Alas, such cruel times," the woman wrote along single-space, dark black lines.

"The night is darkest before the dawn and the dawn is yet to arrive." She signed off as "terribly broken hearted."

The reason for such anguish was obvious.

'Black hole'

The troubled region where some 10 million people live had been placed under a security lockdown on 5 August, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi stripped it of its autonomy and downgraded its status.

The isolation is exacerbated by an unprecedented communications blockade: landline phones, mobiles and the internet were suspended. Kashmir sunk into what a local editor called an "information black hole".

More than a month later - apart from the restoration of what the government claims to be 80% of landline phones - the blockade remains in place.

The woman had put pen to paper after she came across a Facebook post from a freelance Kashmiri journalist who was visiting Delhi.

Manzoor Ahmed has been trying to call his customers from a street-side kiosk

Vikar Sayed, 27, had flown to the capital to access the internet, and pitch some ideas to news outlets.

On a whim, he had posted a message on the social networking site, saying people from his home district in Kashmir could send him messages for their families with their addresses. He would, he wrote, "try his best to reach every address" on his return.

Two days later, Mr Sayed flew back to Srinagar with 17 such messages on his phone from people around the world. They were addressed to family and friends who lived in three districts of southern Kashmir, the most restive region in the Muslim-dominated valley.

Many had sent digital messages. Others had written letters on paper, photographed them and sent them via Facebook Messenger.

The Delhi-based woman - who is not a Kashmiri - was one of them. In her letter, the anxiety triggered by the communications blackout is evident. She writes of how her "fingers have turned sore" dialling numbers in Kashmir without success, and "frantically at night I get up to check my messages, dial a few numbers and go through the pictures of my holiday in Kashmir over and over again".

Back in Kashmir, Mr Syed became an itinerant messenger. He drove out of Srinagar to deliver the messages to homes in shuttered towns and villages. His lifeless mobile phone had turned into a carrier of precious tidings.

A news network is broadcasting video messages from Kashmiris living outside the state

"I tracked down the homes of people, knocked on their doors and showed them the messages on my phone. Most of them were good news."

There were emotional moments. At one home, parents of a college-going son studying in Chandigarh in northern India found out that he had come second in his exam. "His mother hugged me and began weeping," says Mr Sayed.

"You are like my son," she told him.

A communications blackout can end up reviving lost habits. In Kashmir, it has meant the return of letter-writing.

Irfan Ahmed, who is 26, is in love with a university student who lives down his street in Srinagar. They began writing and throwing "paper ball letters" into each other's homes to keep in touch and set up meetings. These were crumpled missives of love, longing and anxiety.

"After the blockade, we could not talk on the phone and meet, so we began to write letters," says Mr Ahmed, who works as an office receptionist.

"We would tell each other how we missed each other, and how cruel this breakdown in communications was. So I would write a reply, crumple the paper, and throw it into her bedroom. We exchanged quite a few."

The blockade has also seen the resurrection of landline phones, which people had largely stopped using.

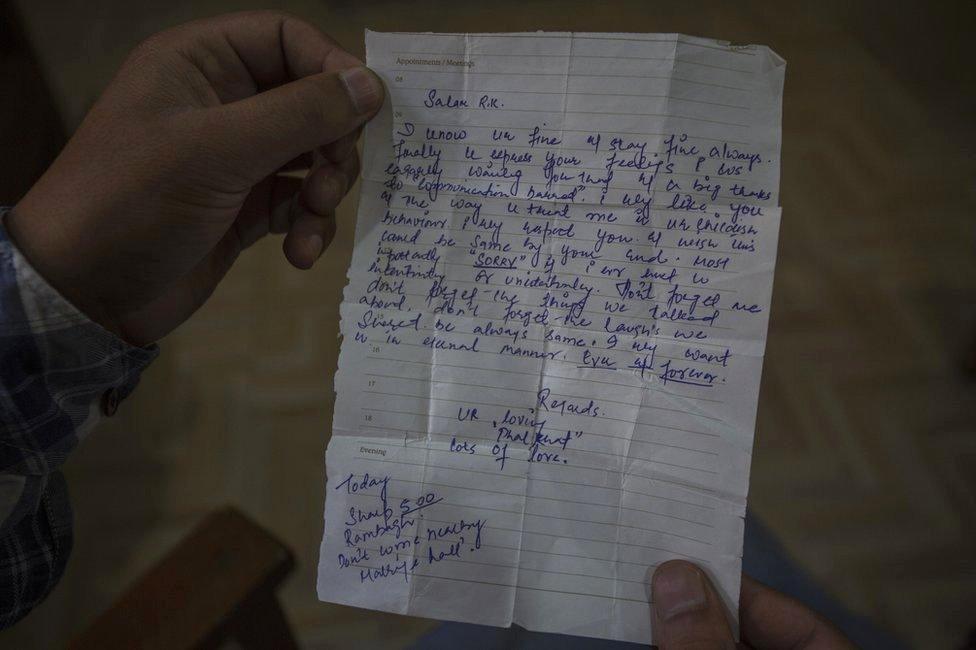

Kashmiris are writing letters to stay in touch

India has more than a billion mobile phone subscribers and 560 million internet subscribers - it is one of the world's fastest growing digital markets. In comparison, there are only 23 million landline phones.

But in Kashmir people are applying for new landline connections or trying to restore unused ones. As the shutdown entered its second month, more such phones sputtered back to life. But people complain that they are often not able to get through to "working" lines.

On the streets security forces have set up free makeshift phone booths - a plastic table, a few chairs and a working Chinese-made phone - and some police stations are offering free calls.

At one booth, Manzoor Ahmed's dilemma was illustrative of how the blockade is hurting people and livelihoods.

The 55-year-old shawl trader was trying to call customers outside Kashmir who owed him money. "They sent me cheques. I went to the bank [some of the banks are open], but they said they have no connectivity and are not able to process the payment. So I am walking around town and looking for a phone to call my customers and ask for a bank transfer," he says.

Internet shutdowns are common in Kashmir

Yasmeen Masrat who runs a one-room travel agency in a part of Srinagar where some lines were restored decided to do her bit to help people connect. She bravely opened her office in mid-August, and offered free calls from her single landline phone.

There are notices on the wall asking people to "make calls short and to the point, as it is chargeable to us". In no time, her office was swamped: more than 500 people have turned up, and made some 1,000 free calls every day since the news of her service spread through word of mouth.

Among them were cancer patients calling doctors and shops in Indian cities for prescriptions and drugs, which are difficult to get locally. One day, a distraught eight-year-old girl arrived with her grandmother. She wanted to speak to her mother, a cancer patient receiving treatment in a Mumbai hospital. They hadn't been able to connect for 20 days. "You get well and come back soon," she told her mother repeatedly.

"It was a very emotional time," says Ms Masrat. "Everyone in the room was sobbing." Another time, a man arrived and called his son to inform him that his grandmother had died some days ago.

And when even landlines are difficult to get through to, Kashmiris living elsewhere in India and abroad are flooding a local news network with messages to their families.

Gulistan News, a Delhi-based satellite and cable news network, has been receiving messages and videos that it plays on a loop during and between news bulletins. It also carries messages from locals in Kashmir. The network says it has run hundreds of messages of cancelled weddings - this is peak wedding season in Kashmir - on an extra scrawl on its English and Urdu language bulletins, as well as video messages from people living outside the region.

Shoaib Mir came to a TV station to report his missing father

One morning last week, Shoaib Mir, 26, arrived in the network's office in Srinagar with a curious request: could they help him track down his missing father?

The 75-year-old from Bemina, some 12km (7.5 miles) away, had gone out for a morning walk the previous week and disappeared. Mr Mir says they searched far and wide and drove miles before filing a missing person's report at a police station. "There are no people on the roads, everything is shut, and the police are busy enforcing the shutdown. Maybe a video message from me with my father's photograph will help track him down," he says.

While the channel has helped connect families, it struggles to do its work. The shutdown has hurt local media like never before. It has made newsgathering difficult. A courier from a news network flies to Delhi every day carrying three to five 16GB pen drives containing footage and news. The material is then edited and broadcast from the office in Delhi.

Local newspapers have shrunk to six to eight pages from the usual 16 or 20. For weeks, some 200 journalists crowded around 10 internet-enabled desktops at a makeshift government media centre in Srinagar. Here, they access email, send stories, pictures and video. Couriers download news from the wires onto their pen drives and run to the newspapers to help them fill the pages.

Mobile phones in the valley are not working

"This place is a test of our patience. The other day it took me seven hours to send some pictures," a photographer says.

Kashmir is not new to internet shutdowns. According to the tracker internetshutdown.in, external, this is the 51st time the internet has been suspended in the region this year. There have been more than 170 shutdowns since 2011, including a six-month-long irregular suspension in 2016.

Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor of Kashmir Times, has petitioned the Supreme Court challenging the information shutdown and curbs on the movement of journalists. She calls it a "grave violation of human rights". The shutdown, she says, also means that media cannot report on developments and residents of Kashmir don't get access to information available to the rest of Indians.

The government says the information shutdown is required to prevent violence in a region that has been wracked by a separatist insurgency for more than three decades. India blames Pakistan for fomenting violence by supporting militants - a charge that its neighbour, which controls a part of Kashmir, denies.

"How do I cut off communications between the terrorists and their masters on the one hand, but keep the internet open for other people? I would be delighted to know," India's foreign minister S Jaishankar said recently.

Local newspapers have shrunk in size as newsgathering has become difficult

But research shows that such shutdowns can end up leading to more violence.

Jan Rydzak of Stanford University who has studied network shutdowns , externalsays they are "found to be much more strongly associated with increases in violent collective action than with non-violent mobilisation". His findings imply that information blackouts compel "participants in collective action in India to substitute non-violent tactics for violent ones that are less reliant on effective communication and coordination".

As Kashmir's future remains uncertain, it is not clear when the information blockade will be lifted or even eased. But there are glimmers of hope. One morning last week, a leased line at a news network in Srinagar miraculously croaked to life. There was muted jubilation. "Maybe things will get better now," says chief reporter Syed Rouf. "We live in hope."

The Indian weddings 'ruined' by Kashmir's lockdown

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Follow Soutik on Twitter at @soutikBBC, external