Turkey-Netherlands row: Erdogan slams Dutch over Srebrenica

- Published

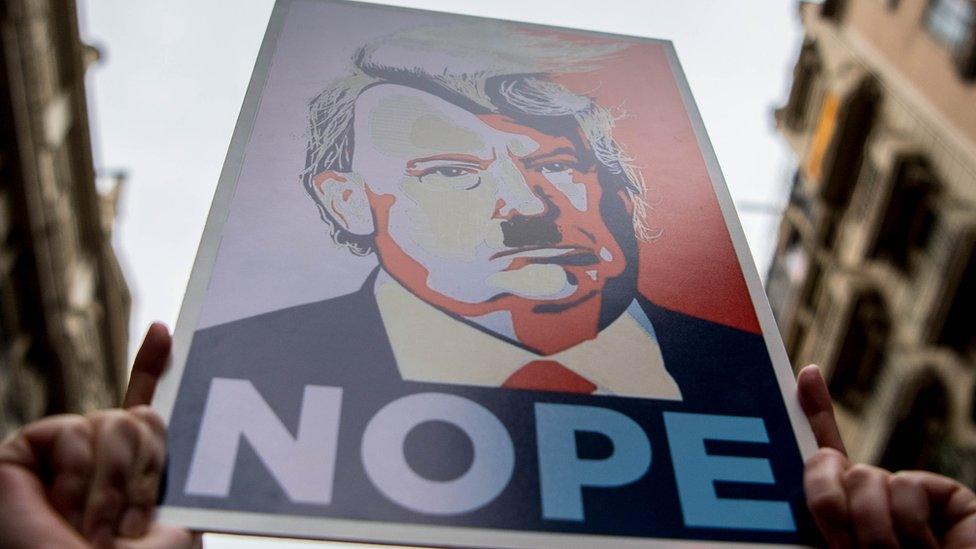

Mr Erdogan has directed a series of controversial slurs at the Dutch

Turkey's war of words with the Netherlands has worsened after the Turkish president accused the Dutch of carrying out a massacre of Muslim men at Srebrenica, Bosnia, in 1995.

Bosnian Serb forces were in fact behind the massacre but Dutch UN peacekeepers failed to protect the victims.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan said the failure, still a raw nerve in the Netherlands, revealed Dutch "morality" was "broken".

The Dutch prime minister called the remarks a "vile falsification".

Mark Rutte told the BBC Mr Erdogan was becoming "increasingly more hysterical hour by hour and I want him to... calm down".

Turkey is furious at a decision by the Netherlands on Saturday to bar two Turkish ministers from addressing expatriates in the country ahead of a referendum in Turkey.

In retaliation, Turkey accused the Dutch of "Nazi" tactics, barred the Dutch ambassador from returning to Ankara, and suspended high-level relations with the Hague in a raft of diplomatic sanctions.

On Tuesday, Turkey's deputy prime minister Numan Kurtulmus said the country may levy economic sanctions against the Netherlands as well.

EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini had called on Turkey to "refrain from excessive statements and actions that risk further exacerbating the situation", but her message appears to have had little effect.

Turkey called the appeal "worthless".

Why did the Dutch ban the Turkish rallies?

The spat began when two Turkish ministers were barred from entering the country to attend rallies that were to be attended by ethnic Turks in the Netherlands.

The rallies were called to encourage large Turkish communities in the EU to vote Yes in a referendum on 16 April on expanding the Turkish president's powers.

The Dutch government decided to block the rallies, citing "risks to public order and security". Some 5.5 million Turks live outside the country, including an estimated 400,000 in the Netherlands.

Police dogs were used to control protesters in Rotterdam

While the Dutch position was that the rallies posed a threat to public order, the EU has made very clear its unease over the Turkish referendum itself.

In their statement, external on Monday, Ms Mogherini and Mr Hahn voiced concern that it could lead to an "excessive concentration of powers in one office".

A look at how tensions between Turkey and the Netherlands unfolded

Srebrenica jibe

Mr Erdogan's invocation of the Srebrenica massacre showed he has no intention of calming the rhetoric being directed at the Dutch.

"We know the Netherlands and the Dutch people from the Srebrenica massacre. We know how rotten their character is from their massacre of 8,000 Bosnians there," Mr Erdogan said.

His remarks touch a raw nerve in the Netherlands, despite a UN tribunal prosecuting Bosnian Serbs for the actual killings.

Mr Erdogan also caused shock and outrage after likening the Dutch to Nazis. The Netherlands was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1940 and occupied right up until the final days of World War Two in Europe, in May 1945. Rotterdam was devastated by German bombing during the invasion.

He has called the Netherlands a "banana republic". The country, which has the sixth largest economy in the EU, is the biggest source of foreign investment in Turkey.

How is this affecting the Dutch election?

The latest development comes just a day before voters in the Netherlands go to the polls for a general election dominated by concerns about immigration and Islamic radicalism.

The anti-Islam Freedom Party of Geert Wilders has long been seen as benefiting from the anti-establishment sentiment which fuelled the victories of Brexit campaigners in the UK and Donald Trump in the US last year.

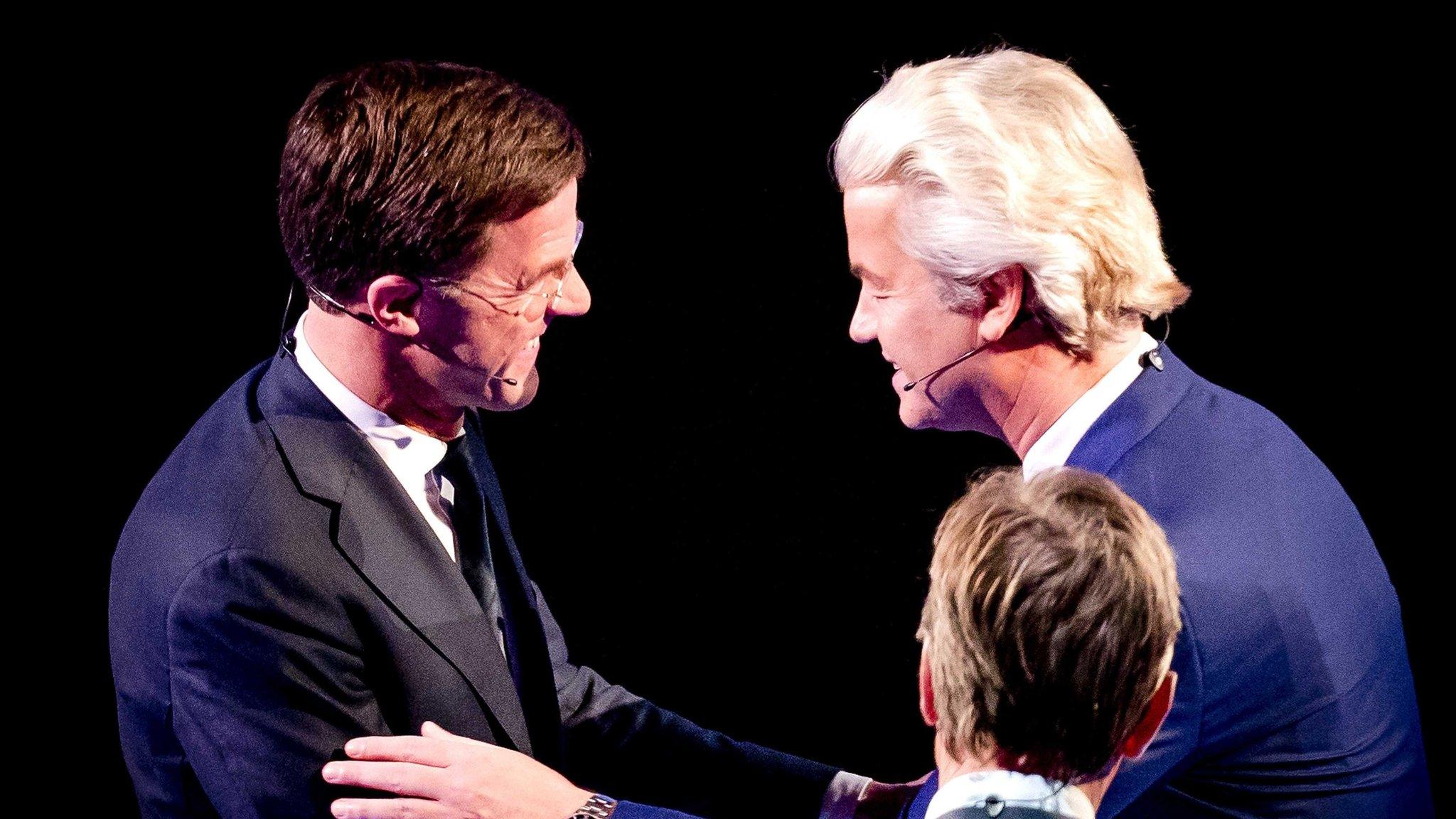

Mark Rutte (right) faces a strong challenge from Geert Wilders (left)

However, Mr Rutte's handling of the Turkish rallies may benefit his centre-right People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), which governs in coalition with the Labour Party.

The Peilingwijzer poll of opinion polls, external suggests the VVD will win 17% of the vote to 14% for the Freedom Party.

Party leaders held a final debate on Tuesday evening.

Could there be wider repercussions?

Mr Erdogan has warned of other, unspecified measures Turkey might take against the Netherlands.

Relations between the EU and Turkey, a predominantly Muslim country regarded as crucial to tackling Europe's migrant crisis, have long been strained.

Turkish officials have suggested reconsidering part of the deal with the EU to stem the flow of undocumented migrants.

The number of migrants reaching Greece by sea dropped sharply after the deal was reached in March of last year.

- Published24 November 2017

- Published14 March 2017

- Published12 March 2017

- Published16 April 2017

- Published13 March 2017

- Published12 March 2017

- Published27 February 2017